There are few monsters who’ve ingrained themselves as deeply in the cultural horror imagination as Count Dracula, on the page, on the stage, and on screen. By the time F.W. Murnau released his shamelessly copyright-shrugging Nosferatu in 1922, thereby incurring the wrath of Bram Stoker’s estate, multiple versions of the story had already been told.

But it’s 1931’s Dracula, ostensibly directed by Tod Browning but actually helmed in large part by its cinematographer Karl Freund, that weaseled its way into the public mind. Bela Lugosi in particular. The jet-black, slicked-back hair, the halting Hungarian speech pattern and suspicious smile, the cloak, the cob-webbed mansion, the seductive sense of Old World charm and/or menace. That, I’d wager most people would say, is Dracula.

Lugosi relished the part for most of his life, came to despise it, and then was buried in costume after his death. His Dracula, so carved into shared fantasy, is simply one of those roles that cannot be escaped. At this point, the feral, vicious image of Max Schreck in Murnau’s film — all long claws, pointed ears, bald head, rodent-like teeth — is barely recognizable as the Count; Lugosi’s portrayal is the one that has endured.

But Lugosi’s debonair visage, apparently terrifying in its time, has also taken a beating over the years. Though it tapped into the eroticism and ambivalence of Stoker’s novel, it’s now more camp than chilling.

Even the name “Count Dracula” seems as likely to conjure up images of a chocolate-loving cereal mascot or a comical Sesame Street vampire who literally teaches kids to “count” as the lord of the undead. It can be difficult to see Browning’s version with fresh eyes nearly 90 years later.

The 1931 Dracula turns out to be one of the weaker of the classic Universal monster movies; the fact that Lugosi made such an impression is almost certainly related to the fact that little else does. The film owes a great deal to the earlier stage play by Hamiltion Deane and John L. Balderston — a Broadway hit in which Lugosi played the title role, thus landing him the gig — and, though visually infused with Freund’s German Expressionist impulses, Browning’s Dracula never really loses that particular staginess. It’s the kind of affair where people gaze out windows and describe what they see to everyone else in the room, and thus to us. Effective in person, maybe, but perhaps not the best use of the camera.

The 1931 Dracula turns out to be one of the weaker of the classic Universal monster movies; the fact that Lugosi made such an impression is almost certainly related to the fact that little else does. The film owes a great deal to the earlier stage play by Hamiltion Deane and John L. Balderston — a Broadway hit in which Lugosi played the title role, thus landing him the gig — and, though visually infused with Freund’s German Expressionist impulses, Browning’s Dracula never really loses that particular staginess. It’s the kind of affair where people gaze out windows and describe what they see to everyone else in the room, and thus to us. Effective in person, maybe, but perhaps not the best use of the camera.

The film runs through the familiar beats — Renfield’s trip to Transylvania to sell a London property to the Count, the rat-infested ship returning with its dead crew, Van Helsing’s suspicions, Lucy in peril, a stake through the heart — but there’s a curious perfunctory sense to the narrative.

Unlike Murnau’s Nosferatu, very few scenes elicit genuine dread or fright. (The ghost ship, so eerie in Murnau and so blase here, with the voyage itself constructed out of interpolated footage from another movie, is a glaring example.) Eventually, Dracula doesn’t come to a climax so much as … end.

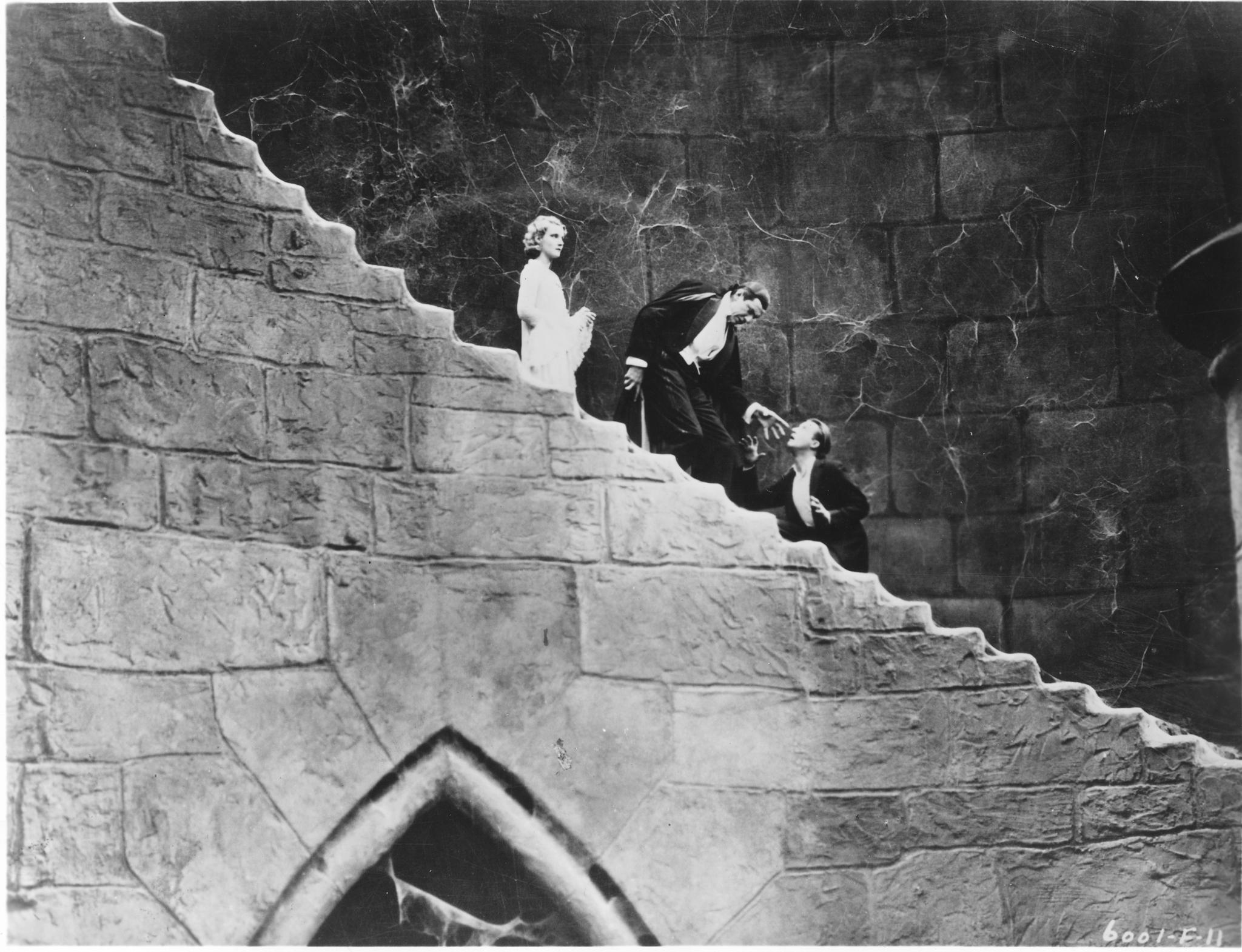

Still, Lugosi eats up the screen like some sort of voracious cinematic blood-sucker, and Freund’s cinematography is effective. Freund — who freed the camera from its station in The Last Laugh, provided indelible futurist images to Metropolis, and even arguably invented the look and feel of the classic sit-com through his work on I Love Lucy — shoots both the Gothic castle and Carfax Abbey as realms of shadows and uneven space. The pinpoints of light that shine in Lugosi’s eyes just underscore his inherently alien Other, and entire scenes set on dramatic, backlit staircases help conjure something otherworldly.

That Expressionist aesthetic also helps center the vast network of open-ended resonances that make up the Dracula story, which are in many ways more interesting than the film itself. The enormous success of the character on film and in pop culture argues for something deeply felt in the character. There’s the fundamental elision of sex and death, blood and flesh — a trope that never seems to wear out its welcome. The vampire figure has been deployed to represent both the capitalist and the communist, a sort of socio-political catch-all for something uncanny in the body politic.

And, of course, there is the issue of Jewish representation. Stoker himself was obsessed with the story of the Wandering Jew; a friend described it as “one of Bram’s pet themes.” The question of how much this subtext informs the story is the subject of extensive literature, not to mention the analysis of what it might mean.

This is, after all, the tale of a strange figure from the East, from over the mountains, apparently rootless but wealthy, who covets the blood of the European bourgeoisie. In the film’s telling, contra Nosferatu, the figure of Dracula is dangerous precisely because of his alien appeal, the way he threatens the structure of an otherwise contented West through the desire and fascination he invokes.

Is this putting too much on a Universal monster flick? In any case, it’s close enough to the surface that, when General Mills introduced a photorealist cereal box featuring the actual Lugosi in 1971, people were less impressed with their technology than horrified by the presence of the six-pointed star he was wearing. The medallion does appear in the early section of Dracula, but it seems likelier have been a prop lying around that helped emphasize the Count’s Old World aristocratic bling, or possibly his military exploits a la Vlad The Impaler, than a Star of David. This was no consolation to General Mills, who promptly axed the promotion.

Such considerations are the subject for a much longer treatment, and this is long enough already. Browning’s Dracula withstands the test of time in large part because of how profoundly it’s been subsumed into later treatments. If the film itself struggles to compete with its own legacy now, there are still moments of startling beauty and even some occasional creepy images. Both Browning and Lugosi would lead rather tragic lives, but the image of this particular Count lives on. We couldn’t kill it if we tried.

What was new about the film was sound. It was the first talking picture based on Bram Stoker‘s novel, and somehow Count Dracula was more fearsome when you could hear him–not an inhuman monster, but a human one, whose painfully articulated sentences mocked the conventions of drawing room society. And here Lugosi’s accent and his stiffness in English were advantages.