Many silent classics, and much art more generally, have drawn on the oldest tales, mining the legacies of myth and the commonalities of familiar narratives to present them anew. Ursula Le Guin writes, “That is the gift the great storytellers have. They tell the same stories over and over (how many stories are there?), but when they tell them they are new, they are news, they renew us, they show us the world made new.” F.W. Murnau’s Faust is a visually spectacular entry in this tradition.

His 1926 masterpiece, the last of what’s termed his German period, came on the heels of The Last Laugh, reviewed earlier in this series. Faust tends to get relegated to some kind of historical-cinematic second-tier, ambitious but flawed (though it has its passionate defenders). And indeed, it was something of a bust at the box office and with contemporary critics like Siegfried Kracauer, champion of Weimar cinema, especially Caligari and Fritz Lang.

But this is a bewildering disservice to his Faust. Mapping this centuries-old story of good and evil — told most famously by Marlowe, Goethe, and Gounod, but dating much further back — onto contemporary concerns, and presenting it with unprecedented practical and in-camera special effects, Faust could just as easily be held up as the pinnacle of German Expressionism, not a footnote to it.

If you are unfamiliar with the tale, in its many overlapping versions, it goes like this. Faust is an aged, learned man, an alchemist who feels he’s exhausted the limits of the world’s knowledge, yet longs for more. He makes a pact with the Devil, trading his soul for a taste of that which has eluded him. The Devil, in turn, has made a bet with an Archangel, hinging on the notion that Faust can be turned to evil and renounce God. After sampling any number of worldly delights, with Mephisto as his guide and servant, Faust grows bored with his limitless power, discovering, usually too late, that he has the whole world at his fingertips but it has come at a terrible cost.

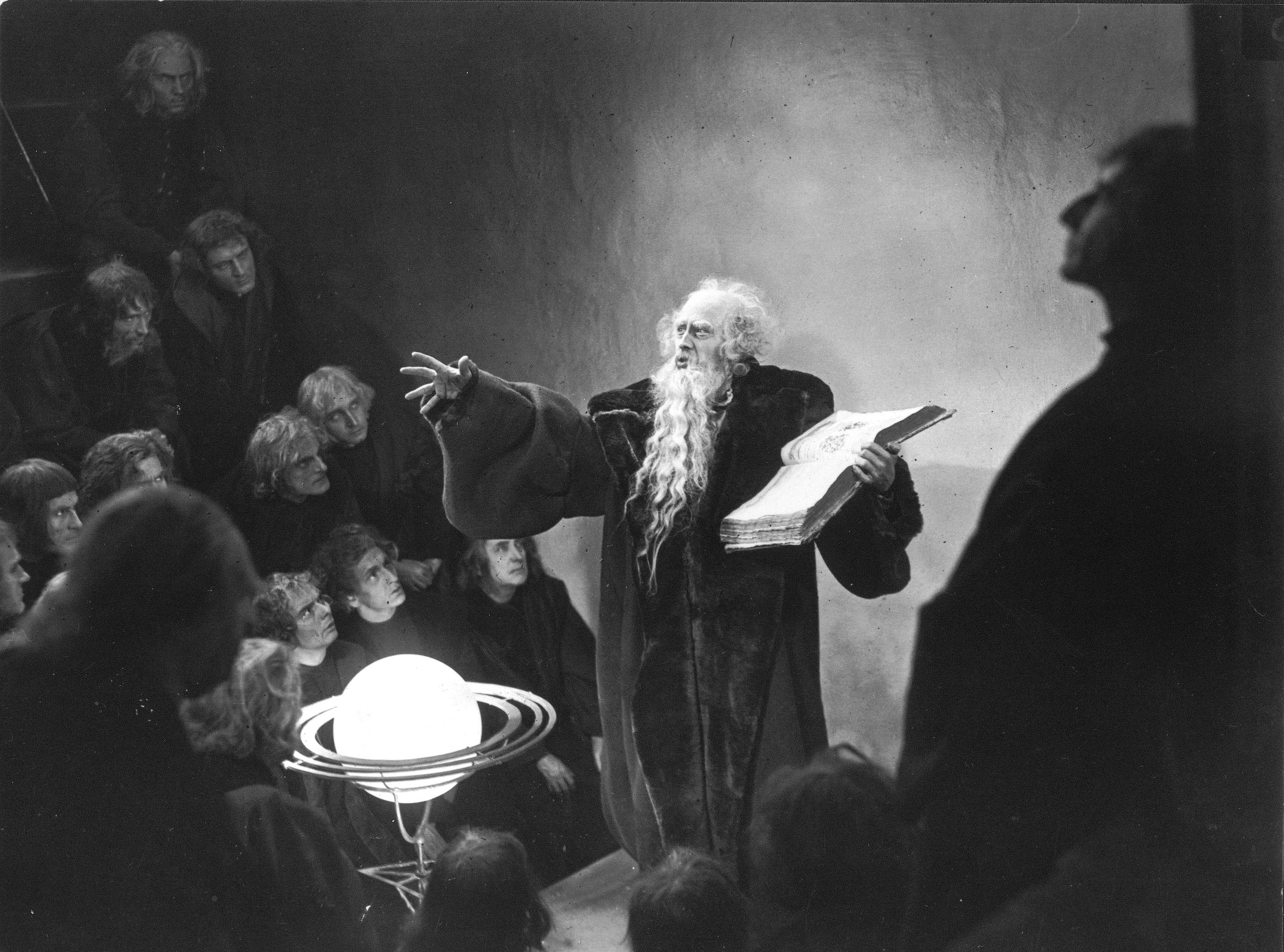

In Murnau’s telling, which meshes several versions of the story, Faust (Gösta Ekman) is an old man unable to use the power of Christ to aid villagers dying of the plague. That plague, of course, was introduced into the village by the Devil himself for the purpose of his game: in exactly the kind of practical effect some of us miss in the age of CGI, Satan (Emil Jannings) looms over a replica with cloak and wings outspread, spreading pestilence and suffering throughout the land. It’s horrifyingly striking, in the way nightmares can only be.

After discovering the power of the Devil instead, Faust brings Mephisto to his side, a wish-granting nemesis in disguise. He cures others, but is shunned by the cross. Instead, he wishes for youth, travels the world, woos a Duchess in Italy, takes a still-incredible magic carpet-ride as the world spreads before him, with all its possibilities.

But he grows bored with this endless ability to fulfill any wish he imagines. Desire outstrips desire, and Faust decides he wants nothing more than to return home. There, he promptly falls in love with pious, ethereal Gretchen (Camilla Horn, in a role the producers hoped for Lillian Gish and, curiously, future Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl wanted for herself).

It turns out it’s not so easy to both sell your soul to the Devil and also romance church-going village ladies. Things take a sharp turn toward violence and then calamity. But at the last moment, and with none of the crowd-pleasing wish-fulfillment of The Last Laugh, our hero is redeemed through the awesome power of love, and his soul saved.

It’s an epic and gorgeous tale spun out through some of the most spectacular images ever committed to film. The world Murnau creates is one of contrast, shadows and light, that literalize the binary struggles at the narrative’s core. Full of superimpositions and set-pieces like the plague scene, the magic-carpet ride, and the visualization of Gretchen’s scream across the countryside, Faust is remains one of the most incredible visual fantasias of all time, testament to a master at the height of his powers.

It’s also a hodge-podge of tones, shifting abruptly from comedy to tragedy, often in a single scene (especially when Jannings is involved, who can be unnervingly realistic one moment, stagy the next, and borderline-Kabuki performer a moment later). A long sequence after Faust’s return home and courtship of Gretchen also features some leering innuendo between Mephisto and Gretchen’s Aunt Marthe, which seems to have arrived from a different film.

But the messiness actually suits Faust here. This is a film that, like its titular anti-hero, wants to be everything at once. The social concerns of the period are reflected in the townsfolk’s treatment of the wretched, abandoned, and mocked Gretchen, but by drawing on archetypal images of struggle in the world, Murnau seems to be after something much more universal than social critique.

Perhaps, like Caligari, his Faust is rooted in the fervor and anxiety of Weimar, with an unsettling focus on the dangers of ambition and epistemic closure that would take a genocidal turn in ensuing years. But the film’s head is in the clouds, where angels and the Devil square off.

It is a fascinating thing that Eric Rohmer, that quiet cataloguer of moment and gesture, wrote his doctoral dissertation on Murnau and Faust. In some ways, it is hard to imagine two more different filmmakers. But a closer analysis, as conducted here, makes very clear how much they shared.

This similarity is, at least in part, because Faust is obsessed with rendering images that accurately depict complicated psychologies and relations. Murnau’s deployment of light — whether the book burning in a fire, the ring around Faust as the Devil is invoked, the world spreading out before him, the clarity of Gretchen’s face during their lovemaking in the woods, the scream emanating through time and space, or just the shadows that create an artifical pinhole POV on the screen — is the mark of someone exploring all that film might do.

For now before the Judge severe

No crime can pass unpunished here

All hidden things must plain appear

That’s a title card from a pivotal scene towards the end, but it could serve as Murnau’s modus operandi here. All hidden things must plain appear. In Faust, as nowhere, else they suddenly do, and an old story seems new again.

Like all silent-film directors, Murnau was comfortable with special effects that were obviously artificial. The town beneath the wings of the dark angel is clearly a model, and when characters climb a steep street, there is no attempt to make the sharply angled buildings and rooflines behind them seem real. Such effects, paradoxically, can be more effective than more realistic ones; I sometimes feel, in this age of expert CGI, that I am being shown too much — that technique is pushing aside artistry and imagination. The world of “Faust” is never intended to define a physical universe, but is a landscape of nightmares. When the elderly Faust is magically converted by Mephisto into a young man, there is a slight awkwardness in the way one image is replaced by another, and oddly enough that’s creepier and more striking than a smooth modern morph.