“You will have the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood,” director Merian Cooper allegedly promised the B-movie actress and future scream queen Fay Wray. She assumed he meant Clark Gable; he meant King Kong.

King Kong, both 1933 classic and imaginative figure, retains one of the more central places in the cultural subconscious. Their lineage includes numerous sequels, spinoffs, sympatico jungle treatments, Jurassic Park, and perhaps every film ever made after 1933 in which a woman is menaced by a beast.

It also has given rise to a cottage industry of analysis focused on its colonial, gendered, and racial subtexts, much to the consternation of fans who’d rather skip all that and simply watch a Giant Ape movie already. (Indeed, just last week I found myself discussing this with irritated NPR listeners, who seemed in no mood to listen to a segment entitled “Can You Make A Movie With King Kong Without Perpetuating Racial Undertones?”)

What’s abundantly clear is that King Kong — like Satan, Dracula/Nosferatu, and, to a lesser degree, Mr. Fuzzypants — refuses to go away. While there’s certainly an appeal to a giant ape destroying everything in his path, it’s hard to imagine retelling this story over and over (and as recently as this month, 74 years after the original’s release), did it not tap into something more essential, knocking down some sort of collective, Jungian door.

If you’ve ever seen a movie, you probably know the story of King Kong, but just in case. An intrepid filmmaker named Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong) sets off to a rumored island off the coast of Sumatra to make his latest epic. He’s apparently well-known for such far-flung, exotic endeavors, and has already enlisted a regular sailing crew to take him there, primarily consisting of Captain Englehorn (Frank Reicher) and his First Mate, John Driscoll (Bruce Cabot).

To Denham’s chagrin, he also finds himself compelled to cast a woman in the picture, because that’s apparently what audiences want these days. After a brief, last-minute search through New York, he lands on the destitute Ann Darrow (Fay Wray), who’s quickly convinced to join this filmic journey into the unknown.

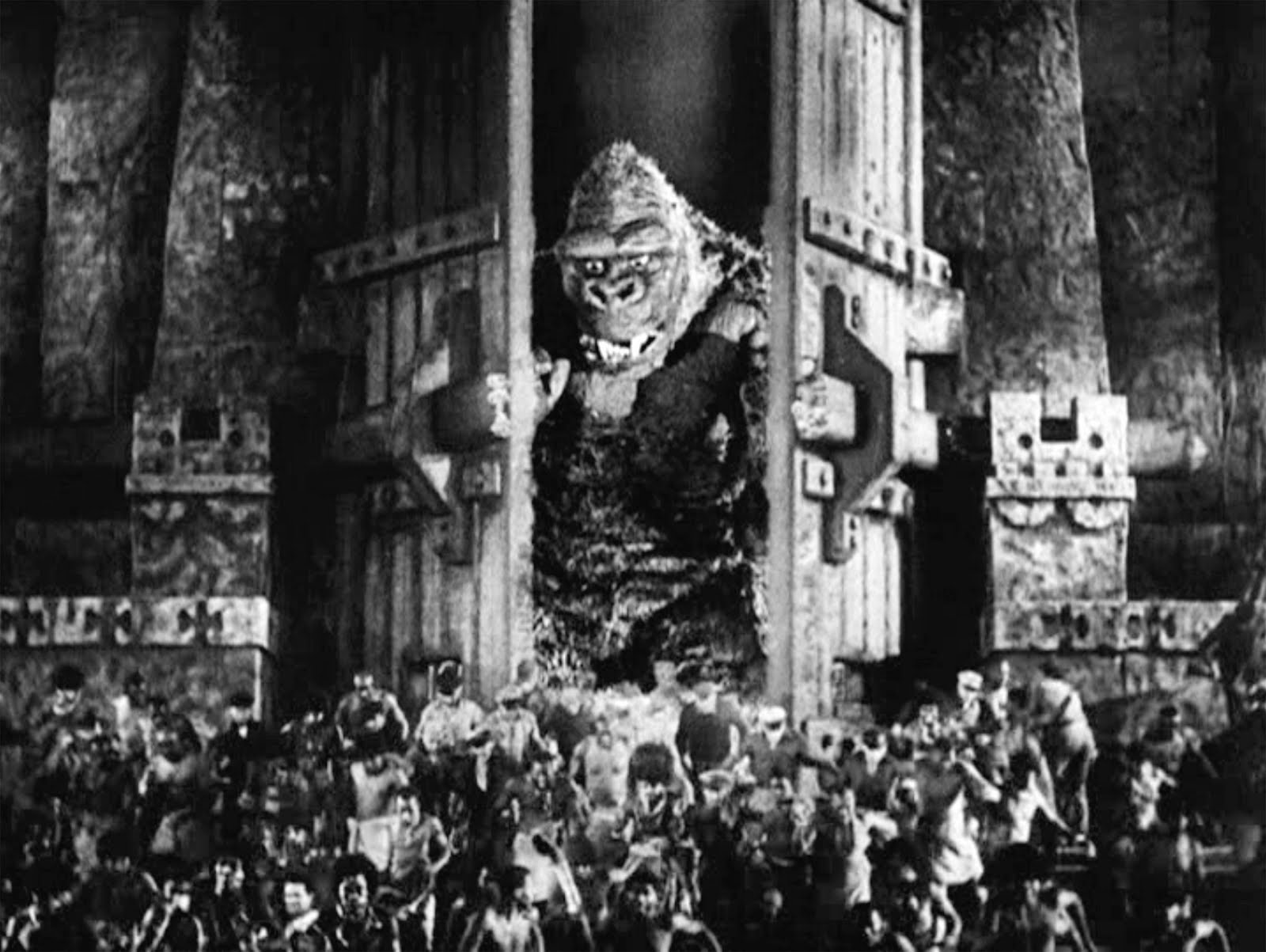

The crew eventually finds the mysterious island, guided through the fog by the drumbeats of mysterious natives who, it turns out, are somehow both African and East Asian and maybe also Mongolian. The savages are preparing to sacrifice a woman to appease a God they call “Kong”, but the arrival of Ann plants a different idea. After trying and failing to trade six of their own tribe for the “golden woman” (“Well, blondes are in pretty short supply here,” Denham quips, quite Denhamly, and also racistly, which are essentially synonyms), they kidnap her and offer her up to the God. That God is, of course, King Kong, the beast deity of this land.

In the familiar twist, King Kong falls in something like love with his white captive, before her true love interest Driscoll saves her. As Kong chases them back and breaks through the door the natives have inexplicably built to keep him out, Denham gas-bombs the monster and brings him to New York for exhibition, billing him as the “8th Wonder of the World” and watching the money roll in. Unfortunately, overzealous press take too many pictures, the flash bulbs freak Kong out, he breaks free, finds Ann sequestered in a bedroom, and hauls her to the top of the Empire State Building. Machine-gun-equipped airplanes take him out, and she’s reunited with Driscoll, while Denham waxes rhapsodic about the whole affair.

King Kong is, in other words, the quintessential B-movie, despite its centrality in the cultural imagination. Shot for roughly  $600,000, starring mostly no-name actors, and with a script co-billed to Edgar Wallace for box-office attention despite a wholesale rewrite, much of the film really serves as a showcase for stop-motion pioneer Willis O’Brien‘s effects (not to mention Max Steiner‘s iconic score). Those effects are impressive to this day, even (or especially) in their jerky, tactile goofiness: not only does Kong fight off the white men with guns and the natives with spears, but he does battle with a Tyrannosaurus, a Pteranodon, a big snake, a Brontosaurus, and a Stegosaurus. Frankly, King Kong has a rough go of it just trying to make it through the day.

$600,000, starring mostly no-name actors, and with a script co-billed to Edgar Wallace for box-office attention despite a wholesale rewrite, much of the film really serves as a showcase for stop-motion pioneer Willis O’Brien‘s effects (not to mention Max Steiner‘s iconic score). Those effects are impressive to this day, even (or especially) in their jerky, tactile goofiness: not only does Kong fight off the white men with guns and the natives with spears, but he does battle with a Tyrannosaurus, a Pteranodon, a big snake, a Brontosaurus, and a Stegosaurus. Frankly, King Kong has a rough go of it just trying to make it through the day.

Watching the film again now, it’s apparent just how much Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack were of their time. The narrative itself draws on the contemporaneous popularity of jungle films and Orientalist exotica, but it also wears its exploitation trappings on its sleeve. The scene — once excised at the demand of censors, now restored in complete versions — where Kong holds Ann in his hand and casually strips her before ostentatiously smelling his fingers is one example.

The notion, so often repeated by the producers, that they were not trying to imply anything metaphorically takes a bit of beating on rewatch. Or, at the very least, reinforces the notion that the creators of art are the very last people you should consult for its analysis. Fay Wray’s frequent state of jungle undress, and the degree to which her character reciprocates the affections of the “tallest, darkest man in Hollywood”, is the subject of continued debate. For my part, there is literally no moment in King Kong when that last part is true, and I agree with Meghan O’Rourke that it is a total misremembering of the film to suggest otherwise. Folks may be confusing the 1933 version with its breathless, shockingly pro-bestiality adaptation from 1976, as Nathan Rabin notes.

This is nothing, of course, compared to one of King Kong‘s most notorious predecessors, Ingagi, which doubled down on the colonialist Orientalism years before, and made a fortune in doing so. It’s one of the most fascinating, racist stories in cinema history, arguably the first pure exploitation film, and almost certainly influenced the construction and marketing of Kong. Not a decade removed from Nanook of the North, Ingagi went ahead and billed itself as the true story of African women mating with primates, to the titillation of Western audiences, and grossed a huge amount of money before its controversial tour had run its course. That colonialism — either as representation, critique, or enactment — is also a large part of the film’s critical history. (Warren Patrick has a good deal to say on this, and I recommend giving it a read.)

One last note on rewatching. This time, I was struck more than ever by the emphasis on film itself. Our “protagonist” (assuming Denham is our protagonist) is, of course, a filmmaker. An early scene on the ship, in which he coaches Ann into the poses she will ultimately experience for real, is one of the more striking touches, implying (like the cameras that send Kong into a fury at the film’s end) that representation itself is part and parcel of the colonial project. It’s also worth noting that he chooses her, after all, specifically because he finds her in a near-fainting state of submission — on his earlier attempt to pick up a would-be starlet, he finds them too brassy and aggressive.

Apparently, the intertwined notions of his representational needs as a filmmaker, the demand for a female star, and the monstrous desire of an ape-man coalesce around her passivity and peril. That her final scene should be set on the Empire State Building — that phallic triumph of industrialism only a few years old at the time of King Kong‘s release — seems appropriate. That her rapacious monster-love should lose his grip on it, and she fall into the arms of her white lover, while audiences below watch with bated breath? Doubly so. Today, they surely would have cell phones held aloft, directing her.

King Kong is a text that cannot be removed from its time and context, but also one that cannot be shrugged off as a simple monster movie. Or at least, so I (and the length of this piece) would argue. The question is never, “What did they mean?” The question always should be, “How does it function? On what presumptions does it draw?”

And on those grounds, we’ll probably never stop talking about a Giant Ape.

On good days I consider “Citizen Kane” the seminal film of the sound era, but on bad days it is “King Kong.” That is not to say I dislike “King Kong,” which, in this age of technical perfection, uses its very naivete to generate a kind of creepy awe. It’s simply to observe that this low-rent monster movie, and not the psychological puzzle of “Kane,” pointed the way toward the current era of special effects, science fiction, cataclysmic destruction, and nonstop shocks. “King Kong” is the father of “Jurassic Park,” the “Alien” movies and countless other stories in which heroes are terrified by skillful special effects. A movie like “Silence of the Lambs,” which finds its evil in a man’s personality, seems humanistic by contrast.