There’s a near-consensus among critics that 2018 was an unusually strong year for film, and I can’t disagree. My list for the year is heavily tilted to the 4-star and above, even with some glaring gaps in the mix – I missed BlacKKKlansman, for instance; I’m waiting to see Roma screened at the Castro in 70 mm, like the cinephile tool I am; I didn’t see the new Claire Denis, or the new Andrew Bujalski, or the new Hang Sang-soo, or the new Frederick Wiseman. Barry Jenkins’ If Beale Street Could Talk hadn’t opened at the time of this writing. No chance for The Image Book.

No matter; I could make 10 lists from the ones I have seen. And, as Richard Brody notes, “The gap between what’s good and what’s widely available in theatres—between the cinema of resistance and the cinema of consensus—is wider than ever.” By “cinema of resistance,” Brody carves out a wide, circuitous ravine through geographies of the image:

Resistance takes many forms, including cinematic ones. But the cinema of resistance isn’t necessarily overtly political (though it may well be that, too—as in many of this year’s best films). Movies of resistance offer, foremost, aesthetic resistance: they resist the making of images and the telling of stories that take their own power for granted. They resist clichés of audiovisual thought, which are as desensitizing to the individual mind as they are deluding in the forum of social debate. They challenge received ideas of what stories and images are, and challenge their makers’ own artistic practices; they expand viewers’ imaginations, deepen and sensitize their emotional responses, and create forms of perception that go far beyond the events depicted in the movies to become enduring experiences in themselves, enduring incarnations of their time.

With this in mind, here are some of the experiences that challenged, energized, and captivated me in 2018. (In alphabetical order, with links to earlier write-ups when appropriate.)

Bisbee ’17

Bisbee ’17

Robert Greene‘s stunningly class-conscious interrogation of memory (always contingent) and forgetting (always political) is as entertaining as it is incendiary. It starts as a documentary about a particularly heinous act of strike-breaking in a mining boom town before morphing into something else entirely, drawing together legacies of racist xenophobia, colonialism, and identities forged through class struggle with the performative act of storytelling itself — the stories we tell about ourselves, our country, and each other. It’s a monumental work.

Burning

Less a mystery, in the genre sense, than simply mysterious, Lee Chang-dong‘s latest is a compulsively perplexing portrait of a trio of young Koreans locked in unstable, indeterminate relationships to each other, to their country, and to their memories. It’s a masterpiece of puppet-string-tugging, indelible performances, and expert use of sound (including the year’s best recontextualization of music – you don’t have to know Miles Davis’ theme from Elevator to the Gallows, just as you don’t have to know the intricacies of Korean formal address, but it sure can’t hurt).

Dirty Computer

Dirty Computer

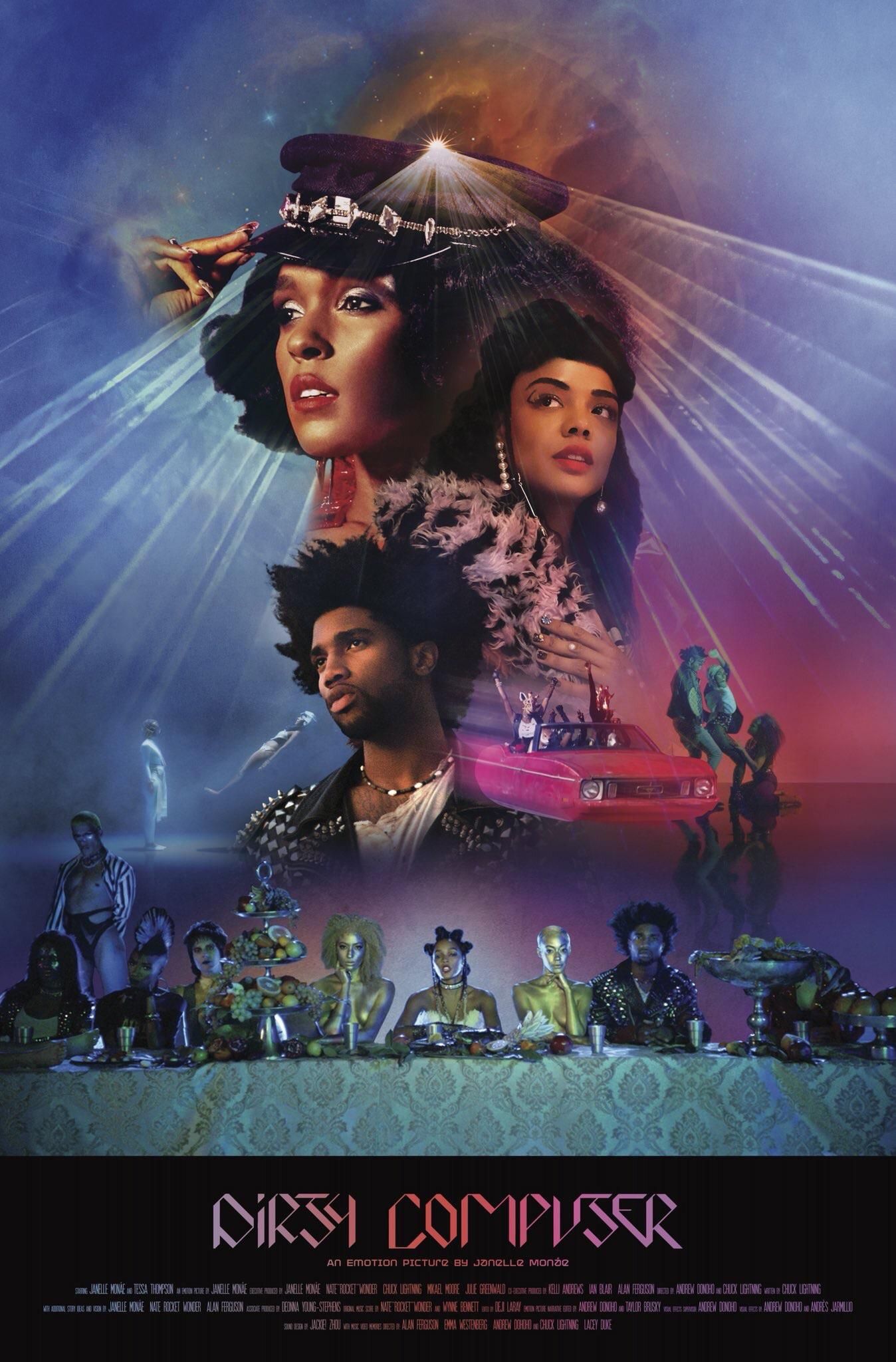

Black Panther has received most of the accolades for 2018’s Afro-Futurism, but Janelle Monáe has been at it for years, and her quirky whatsit Dirty Computer feels like a summation of sorts. The album arrived with a full movie (and Tessa Thompson) attached, complimenting Monáe’s self-reflections and explorations with sci-fi imagery and a narrative about identity erasure and resistance. That YouTube pulled it due to complaints about “explicit content” is so on-brand we might consider it meta-text. 2018 may offer ever more avenues for creators, but system-wide freak-outs in the face of Black Power gender fuckery remain.

Eighth Grade

There was no shortage this year of returning masters, but 2018 was also host to a staggering number of unexpectedly strong debuts from first-time filmmakers. I’m not sure who anticipated the level of empathy, comic realness, and horror-movie-level queasiness of Bo Burnham‘s Eighth Grade, but it definitely wasn’t me. Breakout star Elsie Fisher charms her awkward way deep, deep into your heart as an introvert who makes videos full of advice she doesn’t follow, but it’s Burnham’s emphasis on the sheer, terrifying performativity of growing up today that sticks. No generation has ever had to cope with this level of self-documentation and expectation to constantly reveal, reflect, and deflect, and it’s almost impossible for us olds to imagine. Burnham’s debut, and the hours of YouTube research that inform it, helps.

First Reformed

Paul Schrader’s career-best comes late in the game for him, but thematically it’s right on schedule. First Reformed is 2018’s most serious grappling with climate despair, filtered through Schrader’s fixations on Dreyer and Bresson and anchored by Ethan Hawke in the year’s best performance, and maybe — maybe — its picture of hope in the ruins. In any case, it’s a local favorite around these parts, Brody’s cinema of resistance to a tee.

Free Solo

Free Solo

What impresses most about this white-knuckle chronicle of Alex Honnold’s rope-less ascent of Yosemite’s El Cap are all the ways the filmmaking team finds to bring the story back down to earth. Instead of simply presenting a collection of images of a man on the side of the mountain — terrifying, sure, but of presumably diminishing power — Free Solo breaks down the climb into a series of discrete problems to solve, wonders out loud whether documenting this endeavor is irresponsibly adding, Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle-style, to the danger, and explores, albeit briefly, what it’s like for a man who lives in a van to move into a house. All of this humanizes what it is, in essence, a superhuman feat, sure, but it also gives viewers an inroad, something to hold onto.

Also, those images of a man on the side of a mountain? Fucking terrifying.

Hereditary

In a year full of the horror of intergenerational trauma, Hereditary had the most lasting effect, its juggling of distinct modes of genre storytelling seeming less haphazard in retrospect than part of a larger design. If nothing else, one single, simple shot, with offscreen sound filling in its desperate silence with all the grief in the world, might be the movie moment of 2018.

Hold The Dark

Divisive among horror fans and Jeremy Saulnier fans alike, Hold The Dark is long, cold, and, yes, dark. It rewards patience, but not in the ways you might expect, and it provides windows into myth-level grief and primordial fear, though not in the places we usually look. This is cinema as shadow puppetry on cave walls, buffeted by winds, told together to feel briefly less alone.

Leave No Trace

Leave No Trace

Debra Granik‘s first narrative film in nearly a decade is another kind of elemental wonder, as lush as Hold The Dark is spare. Its focus on stalwart youth in the face of societal constraints — not to mention its staggeringly accomplished first-time lead — recalls her breakthrough Winter’s Bone, but there’s a profound gentleness at the heart of Leave No Trace that sets it apart. The story, about a father and daughter living just barely off the grid, is a wisp of a thing, and the entire film seems in danger of being lost in the endless greenery of the Pacific Northwest, too. But it’s a tender, sad character study, of characters grappling with demons and seeking, in whatever ways they can manage and barely articulate, to hold on to each other. No other 2018 film has grown on me more in the days and weeks since I stumbled out of the vividness conjured in the dark of the theater, out into a world suddenly more alive.

Madeline’s Madeline

Josephine Decker is a pivotal artist of our moment’s complexity, and this immersive depiction of mental illness, performance art, storytelling contradictions, and the ethics of representation is her grand statement, in all its messy, disquieting glory. Decker is seeking something like a new language here, and what she finds is astounding. There’s nothing like it in 2018, or possibly ever. See it right now.

Shirkers

Shirkers

In a year of stellar documentaries, Sandi Tan’s looking-glass-rupturing Shirkers was a standout.

Ostensibly the story of the film she made and lost, Shirkers is a necromancy disguised as a Weird Tale, full of implausible true events, charismatic villains, and cinematic revolutions that never were.

2018 had a special place in its heart and on its screens for this kind of ghost-film nostalgia — the reconstructed memory, the artifact given new, monstrous life — but Tan’s humor and intelligence make this one special. We may never have been gifted the New Singapore Cinema she and her punk rock comrades were plotting to unleash, but we’re lucky to get a glimpse, along with something else — jagged, mysterious, rebellious — entirely.

Shoplifters

Hirokazu Kore-eda specializes in the understated and naturalistic, mining moments of enormous emotional resonance from the everyday. Shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and remains a surprisingly robust domestic box-office draw here at the end of 2018, is all of that and more. Focusing on a semi-chosen family on the social, economic, and moral margins, Kore-eda composes portraits of a Japan we’re not accustomed to seeing on screen, which might help explain its appeal to U.S. audiences. Fundamentally, it’s a clear-eyed telling of a murky narrative, in which the relationships between protagonists are never entirely delineated and hands are rarely held while trying to piece things together. It’s gorgeous and problematic and sad, and it’s final moment is invested with a world of wonder. This one is hard to shake.

Sorry To Bother You

Sorry To Bother You

Speaking of hard to shake! Possibly no 2018 film featured quite the left turn (or Left turn) of Boots Riley’s surrealist grenade from the back row, but the less said about that, the better. If Sam hadn’t already busted out “Groucho Marxism” for Self-Criticism of a Bourgeois Dog, I’d use it for this, another debut of startling confidence. Suffice to say that Sorry To Bother You combined lunatic energy, class-conscious rabble-rousing, and biting satire like nothing else this year. I saw it twice in the theater and I’d go again, if only to marvel at the profound discomfort of a white Berkeley audience to a certain moment in the film. Screen it with Black Panther and Blindspotting for a triptych of 2018 Oakland.

We The Animals

One of the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it releases around these parts, Jeremiah Zagar’s adaptation of Justin Torres’ book unspools like an unusually gorgeous dream. Combining elements of The Florida Project and Moonlight and filtering them through the gauze of late-afternoon light and memory, We The Animals is a special film all its own, a narrative that feels experimental in its emphasis on image motifs and recurrence. It feels like childhood, or at least a childhood. There’s magic in it.

Zama

I’m always here for Lucrecia Martel, even when she suddenly relocates from her native Salta for the first time and plunges into historical setpiece drama, more Aguirre expanse than the horizontal claustrophobias associated with the Argentinian New Wave. Still, this is Martel through and through, from its absurdly detailed sound design to the aching questions of post-colonial identity filled with suspicion and defensiveness – “an absurd, nationalistic identity,” she says; “It’s not a healthy identity.”

All of that absurdity is bound up in the figure of Don Diego de Zama, a minor functionary in a colonial outpost, who imagines some sort of European majesty clings to him even as he’s mired in all the pettiness of empire. Martel’s politics may be hard to pinpoint — the film certainly finds something pitiable and sad in its protagonist, not merely contemptible — but her sympathies are not, and Zama is a film about impossible sympathies. Martel pointedly, strenuously insists she does not care about making movies any more, so we should welcome the ones we get.