Shirō Toyoda’s The Mistress is based on Mori Ogai’s Romantic novel Wild Geese (and sometimes referred to by the title of the original, as Criterion does). The film is in some ways a familiar melodramatic narrative about the crushing of a woman’s desire under patriarchy — a treatment dismissively summarized in 1959 by Bosley Crowther of The New York Times as “a morally mawkish situation upon a tear-misted screen.”

Commentary

I’m pleased to announce the first entry in an ongoing column about the beautiful, challenging films of Abbas Kiarostami is live on CutPrintFilm.

Kiarostami has become a favorite director of mine, and I’m grateful to the CutPrintFilm folks for giving me the opportunity to explore his body of work in more detail.

Earlier this week, The Washington Post’s Alyssa Rosenberg, one of the more nuanced pop culture writers around, published a piece titled “Art is about surrender. Stop asking for it to be custom-tailored.”

Framed as a rejection of the worrying, internet-age tendency to demand narratives that suit audience expectations — not to mention the even more worrying impulse to attack and threaten artists personally for failing to deliver the pre-fab stories some audience members crave to a frightening and pathetic degree — Rosenberg’s piece is reasonable enough.

Many silent classics, and much art more generally, have drawn on the oldest tales, mining the legacies of myth and the commonalities of familiar narratives to present them anew. Ursula Le Guin writes, “That is the gift the great storytellers have.

Do films have to be watched in their entirety? Is that a heretical question even to ask? Is it cinema if you only watch half?

A friend and I were pondering this earlier today, perplexed that more people weren’t showing up for her online programming.

“Well, I ain’t talkin’ philosophies, I’m talkin’ cars,” says the local sheriff in Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry, a 1974 chase movie that was all-but-forgotten until predictable super-fan Quentin Tarantino started peppering his films with references to it.

The sheriff is referring to his own department’s need for vehicles, but out of context it could stand in as the film’s tagline.

The collapsing house that miraculously spares Buster Keaton in Steamboat Bill, Jr. might be the most famous image in the great comedian’s body of work, but the collapsing bridge in The General remains (reputedly) the most expensive single stunt in all of silent film.

Laura Bispuri’s Sworn Virgin is, in her own a words, “a whole discourse on the body.” It’s an exploration of gender fluidity butting up against social norms as rigid as the mountains that surround its central Albanian village. In lyrical flourishes and with quiet, moving grace, Bispuri presents an unusually fraught journey to an authentic self.

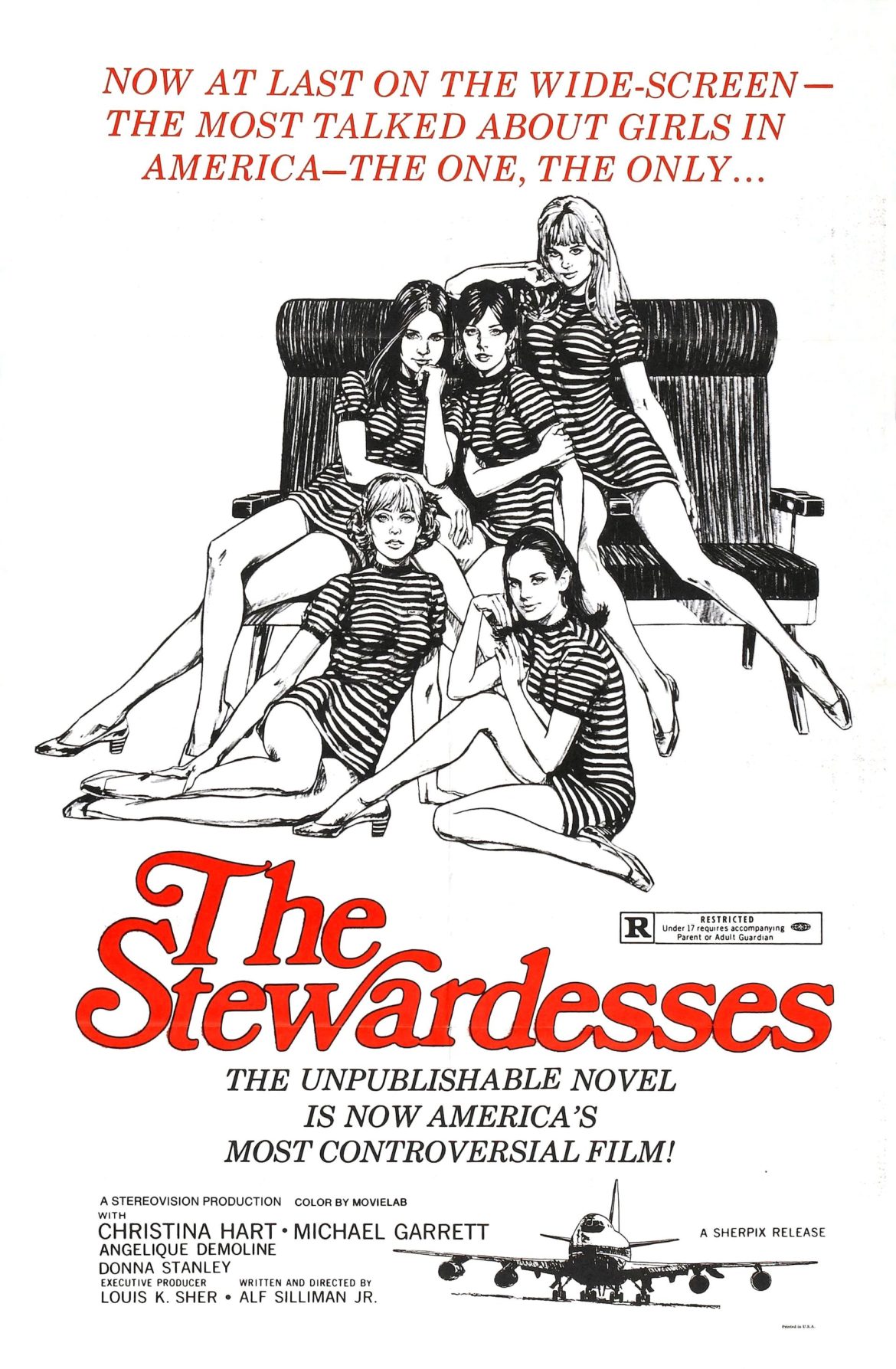

When Gaspar Noé released his excruciatingly boring porno cum arthouse provocation Love in 2015, a lot of ink was spilled about its central conceit: that the whole ponderous thing was shot in 3D, allowing Noé to figuratively spew bodily fluids in the audience’s face.

As Broadway’s longest running musical, “The Phantom of the Opera” tells a story of unrequited, impossible love and longing, set to soaring music and adored by legions of Andrew Lloyd Webber fans. What a surprise it is to discover, then, that its 1925 film incarnation, like the Gaston Leroux novel on which it is based, is a lot more like Saw.