The collapsing house that miraculously spares Buster Keaton in Steamboat Bill, Jr. might be the most famous image in the great comedian’s body of work, but the collapsing bridge in The General remains (reputedly) the most expensive single stunt in all of silent film. The General was Keaton’s favorite of his own films, and, 90 years after barely breaking even at the box office, it routinely finds itself on lists of the greatest in the history of cinema.

It’s not hard to see why, on either score. Audiences didn’t feel they got what they presumably paid for — the wacky hijinks, surrealist comedy, and approachable existentialism of Keaton’s earlier films, unencumbered by narrative drama.

For later viewers, The General has come to represent the culmination of Keaton’s sensibility, the lasp gasp of his independent work before his catastrophic alliance with MGM and steady slide into alcoholism, curious obsession with solitaire, and eventual anonymity in an industry he helped build, only recuperated by legions of cinephiles a generation later.

The General rests on an uncomfortable narrative, but one typical of the times. Based on a real-life incident, popularly retold in an 1863 novel titled The Great Locomotive Chase, in which Union soldiers, led by a civilian, staged a daring raid to steal a Confederate train. Keaton reversed the emphasis: he plays Johnnie Gray, a train engineer who finds himself trying to recover that train from the conspirators. (In real life, those Northerners were hanged: unsurprisingly, The General doesn’t touch on this pesky detail.)

As so often, the narrative is rooted in the Keaton character’s failed attempts to impress a woman who he hopes to marry. When war breaks out — located here, as throughout Lost Cause cinema, with the firing on Fort Sumter, not in the legacy of the slave trade — he rushes to enlist, but it’s decided he’s more valuable on the homefront as an engineer. Despondently, he slinks away, leading his belle and her family to consider him a coward instead.

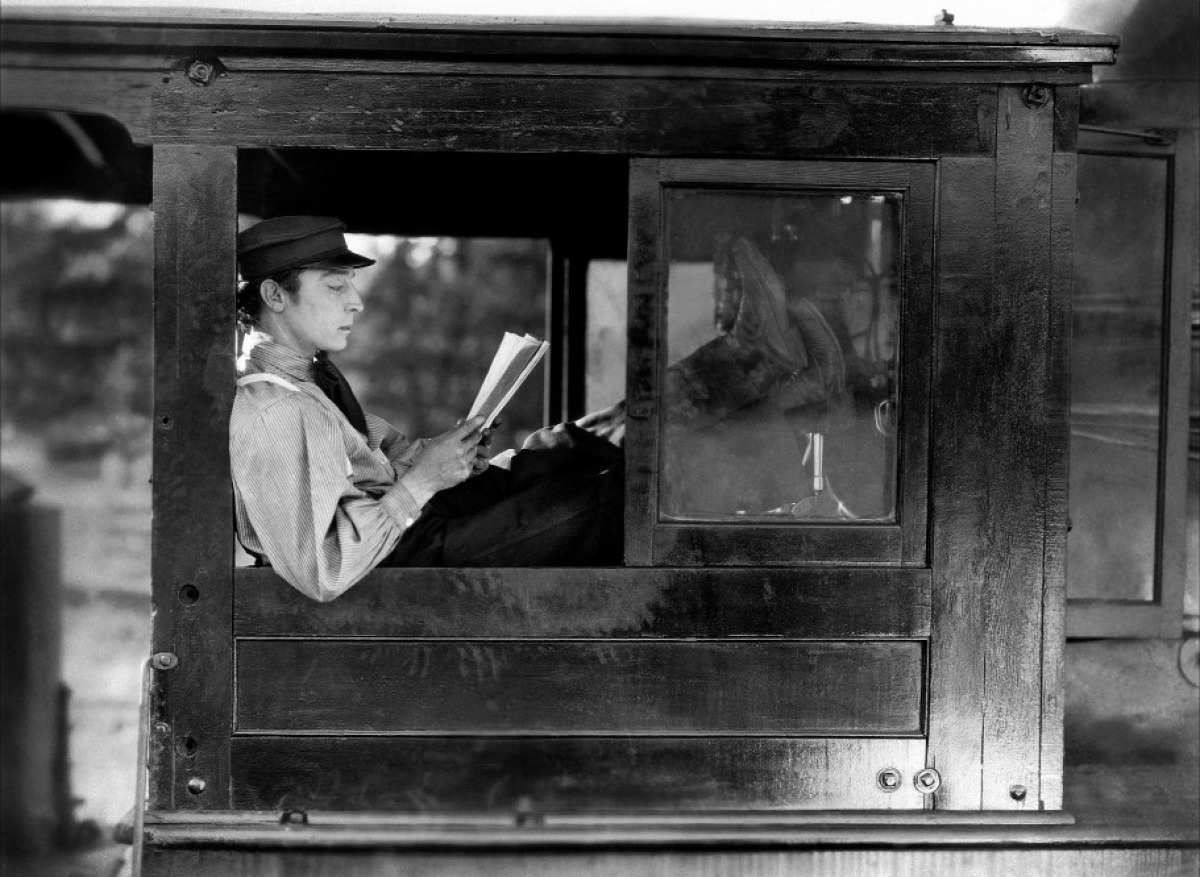

Almost immediately, he gets a chance to prove his mettle. Union soldiers steal his train, The General, with his love on board, and we set off on a feature-length chase film.

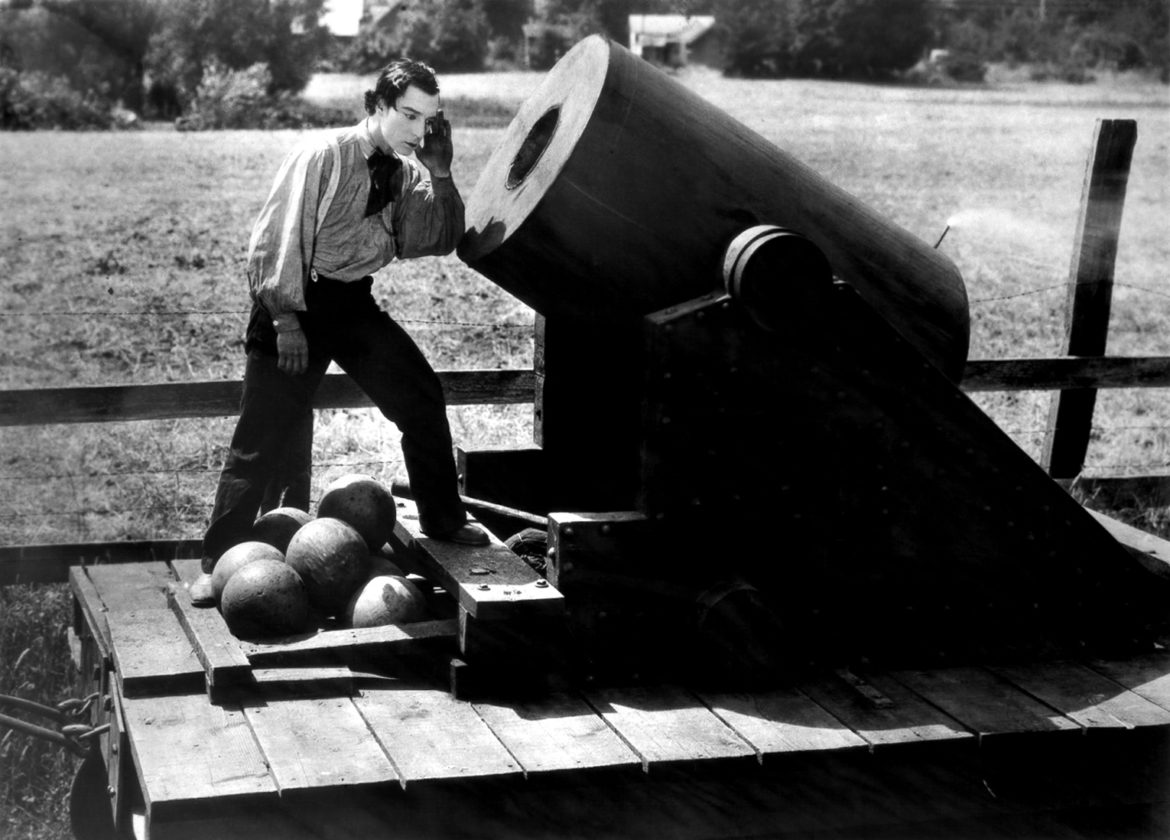

Cleverly rooted in Keaton chasing their train and, in the film’s second half, their train chasing him, it provides ample opportunity for characteristically outlandish stunts — running across train tops, removing planks of wood from the track as he sits on the front, comic setpieces that rely on his obliviousness to everything but what is directly in front of his view.

As a director (along with Clyde Bruckman), Keaton had a genius not just for the justly lauded, and absurdly dangerous, physical comedy, but for framing images and timing. We always know more than he does — it’s a comic gift to an audience, who laugh at the absurdity of his earnest attempts to affect a world that seems to have it in for him.

But, of course, he always pulls through, barely. Keaton’s filmic world is constructed of chance, tragic and comic in equal measure. Cinematically, it’s in the long-shots he loved so much (“Close-ups are too jarring on the screen, and this type of cut can stop an audience from laughing,” he said) — we’re watching under the aspect of eternity, and if it’s funny, it’s funny to the exact degree that we recognize both his character’s vulnerability, the looming danger, and the complete happenstance that defines his survival. His deadpan expression is the look of a man trying to do the right thing in a world gone mad; the stiller the face, the greater the idiocy, the bigger the laugh.

Taking place in Marietta, Georgia but filmed in Cottage Grove, Oregon, The General is several steps removed from its source material, which is deployed far more for the physical possibilities it offers than anything resembling the political. But all art is political: certainly in a story of the Civil War, based on a true narrative of Union exploits rerouted to a Southern perspective because Keaton explicitly believed “It’s awful hard to make heroes out of the Yankees.”

His reasoning, as explained at length by Eileen Jones, is less absurd than it might sound. Jones traced the history of Southern Lost Cause narratives on film, and found them the overwhelming majority of cinematic treatments. Underdogs play better in narrative, for one thing (and in comedy, Keaton would say). It’s a weird rerouting of today’s notion of “punching up” — only in this case, the idea is you ought not to beat up on an already defeated seat of white supremacy. That’s not, I imagine, something that makes a lot of sense to modern considerations.

But there are larger considerations — a longing for an agrarian past that never was, animated by current concerns; a desire for platitudes about reconciliation rather than conflict, and the primacy of the family or love relationship in the process; a desperate desire to code or sublimate actual white supremacy under cover of a vague humanism or anti-war paean to Brotherhood; so forth. This tendency began with Birth of a Nation and is carried through all the odes to Southern nobility, all the way to the Western. As Jones writes:

Agrarian utopias can take root in a sparsely settled wilderness, which also raises the possibility of growing townships, new industry, railroads, and all the trappings of modernity as either a threat or a promise, or both. The honor code of the Southern gentleman can be absorbed into and somewhat disguised by the character of the free-ranging Western hero whose past is often obscured. A cross-section of regional types from North and South can mix together in barrooms and on stagecoaches. And “the Negro problem” is nicely avoided out West, where slavery never spread. Or rather, it’s transformed into a common enemy that white Northerners and Southerners can fight together as “the Indian problem.”

These are animating concerns that haunt even The General, a film that, it should be said, doesn’t have an overtly racist bone in its body. (Keaton’s The Paleface? Yeesh, maybe not so much.) But the point isn’t to “absolve” art: it’s simply to recognize the context in which it arises. This is, after all, the heroic story of a Southern man who blows up a bridge to save a slave-owning community from attacks by marauders who want, among other things, to end slavery. Played for laughs. That doesn’t sit all that comfortably, and every critique of The General that ignores it in favor of a focus on the mastery of physical comedy is, at least in part, willfully obscuring a crucial issue that haunts both society and our representations of it to this day, in ways that demonstrably kill.

So Buster Keaton’s a murderer? Of course not. He was a product of his time, with a shrewd understanding of what would play on screen and, in my opinion, the greatest comic presence in the history of American film. Or at least the one I relate to the most. There’s a deep loneliness that underwrites the “Stoneface” character, a sense of ludicrous imperturbability in the face of constant catastrophe that surely kept audiences at arms-length in a way that sabotaged greater success in his own time, along the lines of a Chaplin or a Lloyd. It is deeper and richer than either of those genius’ legacies. The moment when Union soldiers run one direction off-frame, and then the actors switch to Confederate uniforms and run back the other way is a facile notion that erases difference, a great gag that echoes the film’s larger structure, and an absurd vision of war. It’s all those things.

The point is not to castigate art from a moral distance, but to understand how and why it was made, why it worked or didn’t work then, and the context in which it exists today. The General never succumbs to the worst impulses of the time, but it’s still both a deeply uncomfortable narrative and a work of inimitable genius. It’s emblematic of a narrative impulse that underwrites American film, and it’s a showcase for a superbly athletic Vaudevillian with philosophical leanings.

It’s a masterpiece, and masterpieces need unpacking. Even the silliest and the most accomplished. The General outlives many of its contemporaries precisely because it is so rich, hilarious, spellbinding, and inherently troubling. Buster Keaton was one of the best we ever had, and it would be a disservice to him to pretend otherwise.

Today I look at Keaton’s works more often than any other silent films. They have such a graceful perfection, such a meshing of story, character and episode, that they unfold like music. Although they’re filled with gags, you can rarely catch Keaton writing a scene around a gag; instead, the laughs emerge from the situation; he was “the still, small, suffering center of the hysteria of slapstick,” wrote the critic Karen Jaehne. And in an age when special effects were in their infancy, and a “stunt” often meant actually doing on the screen what you appeared to be doing, Keaton was ambitious and fearless. He had a house collapse around him. He swung over a waterfall to rescue a woman he loved. He fell from trains. And always he did it in character, playing a solemn and thoughtful man who trusts in his own ingenuity.