Battleship Potemkin and Sergei Eisenstein, its visionary creator and Soviet film theorist, loom so large over the history of cinema that there seems little left to say at this point. Treatises, books, films, encyclopedia entries have all been produced on the film’s tale of mutinous sailors and the triumph of the proletariat over murderous Czarist forces.

Potemkin burst onto the scene in 1925, poorly received in the new Soviet state where audiences were just beginning to enjoy the imported narratives from abroad but, ironically, widely championed for its formal daring in the very places producing those narratives. There are many pieces of criticism heralding its innovations, and many are very good.

If a little exhausting. Nearly any discussion of montage in a given film now will feel obliged to trot out the term “Eisensteinian”, with or without explanation and whether or not it’s actually germane to the topic.

The “Odessa steps” sequence revolutionized film grammar while also startling and scandalizing enough audiences that Potemkin was banned in the U.K. through the ‘50s; by our time, in turn, it’s enough of a cliché to be included in outlandish comedies like Naked Gun 33 1/3 and The Untouchables. (Was De Palma’s film not a comedy? My mistake.)

As a consequence, Potemkin’s actual effect is somewhat lost in the historical notes and anxieties of influence it produced. Instead of formalist analysis (this one is fine) or deep dives into the material conditions of its development and creation (here’s a well-done entry from a sectarian Marxist), we are going to aim for something a bit more basic. Namely, what is it like to watch Battleship Potemkin in 2016?

As a consequence, Potemkin’s actual effect is somewhat lost in the historical notes and anxieties of influence it produced. Instead of formalist analysis (this one is fine) or deep dives into the material conditions of its development and creation (here’s a well-done entry from a sectarian Marxist), we are going to aim for something a bit more basic. Namely, what is it like to watch Battleship Potemkin in 2016?

I agree with those who say films must be received and evaluated within the contexts of their time and place, and that couldn’t possibly be more true than something like Battleship Potemkin. But we also encounter them in a time and place of our own.

The first and most obvious point is that the film’s propaganda function is so overt as to be almost laughable. When villains actually twirl their mustaches villainously while sending men to die, you know you are not in the most subtle narrative possible.

The first and most obvious point is that the film’s propaganda function is so overt as to be almost laughable. When villains actually twirl their mustaches villainously while sending men to die, you know you are not in the most subtle narrative possible.

Still, this is to be expected – Potemkin’s propaganda function is its defining characteristic, whatever the formalists might argue. There are more interesting aspects.

Still, this is to be expected – Potemkin’s propaganda function is its defining characteristic, whatever the formalists might argue. There are more interesting aspects.

A striking one is the heavy reliance on title cards. This surprised me, on this fifth or sixth watch: for all the well-deserved accolades about the film’s dynamism and emphasis of movement, it’s startling to see how frequently the action is broken by unnecessary exposition.

A year prior, Murnau told a deeply individualistic story in The Last Laugh without a single title card (except, of course, for one, the dumbest in film history). This individualism itself is at a huge remove from Potemkin‘s project, which is in many ways the cultivation of an anti-individualistic aesthetic. Still, the received wisdom holds that this collectivity will be constructed from pure image and visual juxtaposition. Strange, then, that Eisenstein breaks up the rhythmic flow with regular interjections, often simply repetitions of the previous line with exaggerated emphasis.

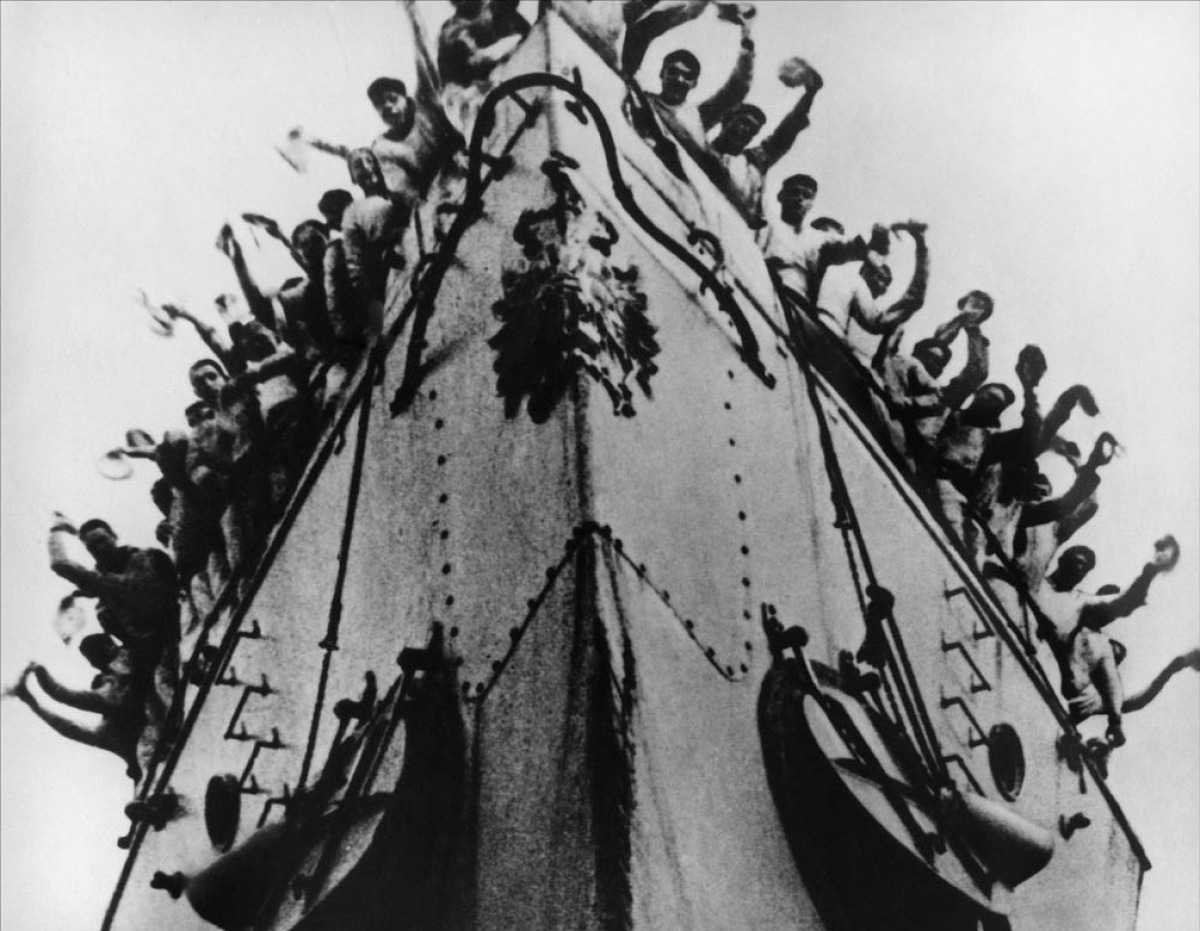

On the other hand, the two central set-pieces – the massacre of common people on the Odessa steps and the climactic, nail-biting naval engagement between the revolutionaries and those sent to destroy them – are indeed thrilling. The editing is justly lauded. But more than the montage itself, it’s striking to see how his theories of “conflict” are embodied in the frame.

The most jarring images are often not the most famous, which tend towards bloodied close-ups or teetering baby carriages, but the juxtaposition of light and dark, and a huge emphasis on contrasting angles that put you on edge. The viewer is fully aware, as any Marxist would encourage her to be, of oppositions and tension, rendered aesthetically in lines and form. These sailors at rest in overlapping hammocks is a good example:

The most jarring images are often not the most famous, which tend towards bloodied close-ups or teetering baby carriages, but the juxtaposition of light and dark, and a huge emphasis on contrasting angles that put you on edge. The viewer is fully aware, as any Marxist would encourage her to be, of oppositions and tension, rendered aesthetically in lines and form. These sailors at rest in overlapping hammocks is a good example:

So is this rather erotic sailor image, more Kenneth Anger than Marx and Engels:

So is this rather erotic sailor image, more Kenneth Anger than Marx and Engels:

It’s not a far leap from the jagged positioning of looming white-coated troops and helpless victims below on the Odessa steps to the most characteristic aspects of Soviet Realist painting and design. Interestingly, Eisenstein, the patron saint of motion and montage, seems just as much an influence on the static art meant to convey collision.

Even at little more than an hour, though, Battleship Potemkin can drag, despite moments of extreme tension and carnage; lay this at the feet of the polemical title cards. It’s still an extremely engaging movie, an action flick before that was even a term. (Indeed, Matyushenko and Vakulinchuk, the first two characters introduced, seem to prefigure some sort of revolutionary buddy-tragedy, as opposed to buddy-comedy.)

The formalist constructions are of enormous import, and there are obviously issues of world-historical consequence at play, but Battleship Potemkin is also still a movie about mistreated dudes stealing a ship and sticking it to the bastards who fed them rotten meat and shitty soup.

They are undermined by superiors, linked to their comrades, and out to make a difference, no matter the cost. This is the logic of the action movie, one imbued with political content even in a non-revolutionary context.

I’ve emphasized the difficulty of writing something new about Potemkin. The question, fair enough, might be raised: why write anything at all about it, then? Obviously, I was prompted by this series to do so, but more generally, I think it’s similar to the rationale for revisiting texts in the first place. As a gauge of where you are, as a viewer and participant, that kind of engagement in valuable. If there aren’t exactly new scenes to discover, there are always new experiences to process. If there aren’t profound revelations, there are resonant moments of connection and disjunction, and an awareness that the viewer, however positioned, helps create the text. Potemkin is a classic for many reasons, but one of them is surely its ability to be found, image by image, strange again.

That there was, in fact, no czarist massacre on the Odessa Steps scarcely diminishes the power of the scene. The czar’s troops shot innocent civilians elsewhere in Odessa, and Eisenstein, in concentrating those killings and finding the perfect setting for them, was doing his job as a director. It is ironic that he did it so well that today, the bloodshed on the Odessa Steps is often referred to as if it really happened.

Part of an ongoing effort to watch each of the films in Roger Ebert’s Great Movies series. The introduction and full list can be found here.