As legend has it, Anger (born Kenneth Anglemyer) filmed Fireworks in his parents’ Hollywood home while they were away for the weekend. Like Cocteau’s Blood of a Poet and Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, both earlier entries in this series, Anger’s short takes the form of a “trance-film,” a series of images that don’t merely blur the division between the fictive and the real but destabilize the notions themselves. (Anger himself called Fireworks “a dream of a dream.”)

Should we summarize the “plot” of a dream?

Fireworks opens on a skewed vision of the Pieta, with a sailor clutching a prone man in his arms, before seguing onto a sleeping figure (Anger himself), seeming to awaken, seemingly with an erection. He removes the bedsheet to reveal what seems to be a carved African idol of some sort where the phallus would seem to be. He gets dressed, languorously, the camera lingering on his torso and, briefly, his crotch.

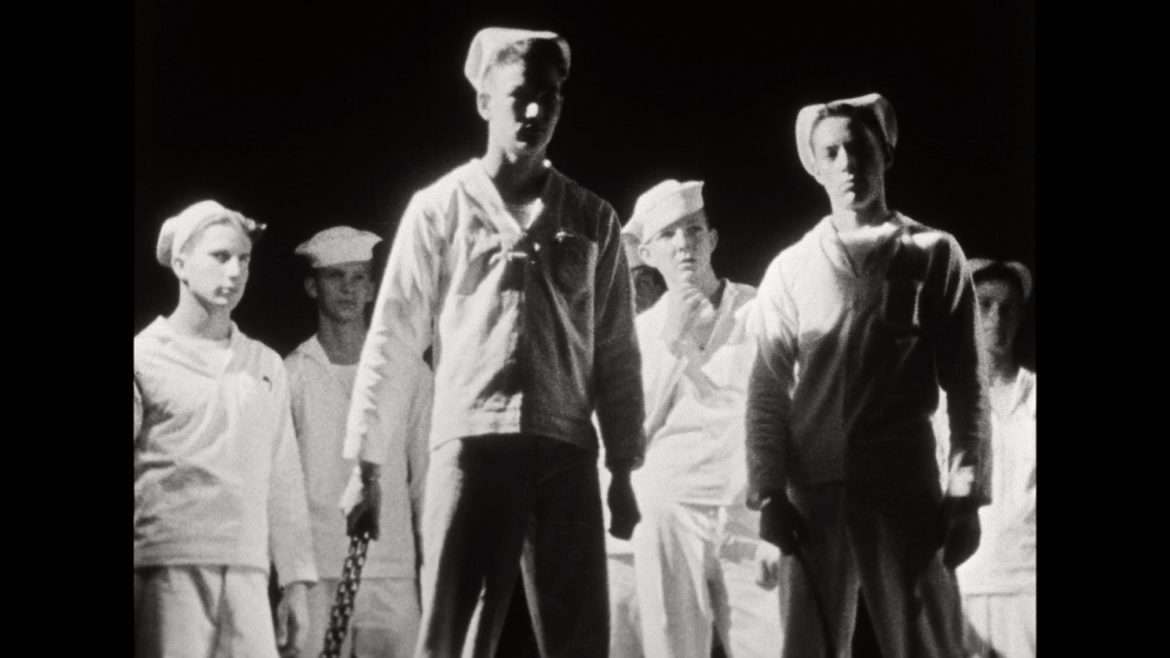

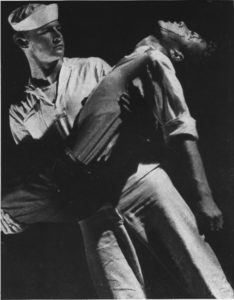

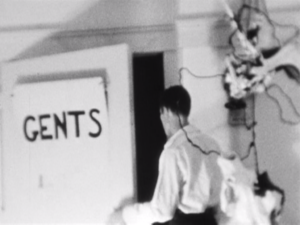

A door on the other side of the room reads “GENTS”, with a wire sculpture dangling in front of it that unmistakably recalls Cocteau, and he enters. On the other side, he encounters a sailor, bare-chested and flexing. We cut back to the original room, where the sailor lights our protagonist’s cigarette with a flaming pile of sticks. (The first, but not the last, bit of linguistic camp Anger has up his sleeve.) Still smoking, Anger re-enters the GENTS room, where he is brutally – and, by all evidence, willingly – assaulted by what has now become a group of sailors, all fists and chains and metal rods.

The camera flashes over his face again and again as fingers plunge into his nostrils, releasing a torrent of blood and fluid. A bottle of milk is smashed over him, and glass from the bottle is used to eviscerate his chest, revealing a mechanical heart. The milk itself than pours over his body, viscous and white, washing away the blood. He is again physically intact after the violations.

He once again enters the “GENTS” room, which now leads, as one would’ve initially expected, to a row of urinals, before which we briefly glimpse our protagonist, prone, now wearing the sailor’s cap.

We jump-cut back to the bedroom, where the original bare-chested sailor approaches. The sailor opens his pants to reveal an explosion of the titular fireworks emanating from his crotch, and we close on a jumpy image of the two in bed, with physical scratches to the film creating a halo of light around the dream-sailor’s head and eyes, and what seems to be a Christmas tree on fire.

Much has been written about “what it all means” – from analysis as the pre-Stonewall fantasies of queer youth to deep Lacanian readings about phallic displacement and “masochism as an act of subversion” – and I certainly won’t pretend to know. The overriding sense is one of loose connection – of desire, violence, submission, transgression, explosion as processed metaphorically and viscerally in turn. As in Blood of a Poet, the body is centralized and made profoundly unstable and vulnerable, and as in Meshes of the Afternoon, there is never certain, solid ground on which to stand, as allusions multiply and contradict.

Iconic figures of masculinity take on different, fraught resonances (and may come replete with low jokes: seaman, semen). Even milk, that “wholesome” staple of the All-American diet, is deployed with tongue firmly in cheek. As a teenager, Anger exploded in Fireworks as a fully-formed provocateur, even if it’s never quite clear what he’s “saying.” If we’re to take him at his word, it’s this: “This flick is all I have to say about being 17, the United States Navy, American Christmas, and the Fourth of July.”

That’s probably true, as far as it goes. But the fact that it’s up for debate for 70 years later, and still manages to scandalize probably means he did his job.

Part of an ongoing effort to watch a set of films from non-White, non-U.S., non-male, and/or non-straight filmmakers and depart a little from the Western canon. The intro and full list can be found here.