In 1928, following the one-two punch of his celebrated U.S.-made releases Faust and Sunrise, and four years after he made The Last Laugh for UFA, the great German director F.W. Murnau predicted that the “films of the future will use more and more of these camera angles, or, as I prefer to call them, these dramatic angles. They help photograph thought.”

This is a much more useful vantage point from which to consider The Last Laugh than its famous plot synopsis, attributed to historian Stephen Brockmann: “a nameless hotel doorman loses his job”. True enough, as far as it goes, but not quite the whole story.

This is a much more useful vantage point from which to consider The Last Laugh than its famous plot synopsis, attributed to historian Stephen Brockmann: “a nameless hotel doorman loses his job”. True enough, as far as it goes, but not quite the whole story.

Murnau’s 1924 silent, shot by the legendary Karl Freund and starring a pre-disgraced Emil Jannings, does indeed hinge on that narrative. But its influence – on everyone from Welles to Ozu – is far greater than Brockmann’s cheeky summation would imply. But let’s start with the story, credited to Carl Mayer, anyway.

The portly, genial-looking Jannings is a doorman at the Atlantic Hotel, a glistening totem of modernity and luxury the film contrasts with the modest working-class tenement he inhabits. Jannings, sporting a ludicrously full beard and Father Christmas twinkle in his eye, is proud of his job and his doorman’s uniform, and is treated almost as a celebrity by his neighbors, who fawn over his arrivals and departures from home. In obsequious postures that come off as so hammy even by the generous standards of early silents that they almost feel ironic, the neighbors cheer their resident success story.

But we can tell right away that things will take a turn. Jannings is increasingly struggling to carry the hotel guests’ luggage, his large frame looking less respectable than a bit silly. When he takes a break to catch his breath at work, his manager makes a note of it. It comes as no real surprise when he’s summarily pushed out of the position for someone younger. To add insult to injury, he’s not only stripped of the uniform that constitutes his identity, and that allows him a sort of class mobility and ease, but demoted to washroom attendant. Jannings the actor seems to shrink on screen to a shadow of his former self – stooped and chastened, his superiors may as well have castrated him, as far as he’s concerned. It’s a precipitous fall from grace.

But we can tell right away that things will take a turn. Jannings is increasingly struggling to carry the hotel guests’ luggage, his large frame looking less respectable than a bit silly. When he takes a break to catch his breath at work, his manager makes a note of it. It comes as no real surprise when he’s summarily pushed out of the position for someone younger. To add insult to injury, he’s not only stripped of the uniform that constitutes his identity, and that allows him a sort of class mobility and ease, but demoted to washroom attendant. Jannings the actor seems to shrink on screen to a shadow of his former self – stooped and chastened, his superiors may as well have castrated him, as far as he’s concerned. It’s a precipitous fall from grace.

The former doorman can’t allow anyone at home to discover his professional failure, and so he steals back the uniform. If he must suffer indignity at work, his self-construction and class-consciousness can’t allow it at home, so he attempts to keep it secret and thereby maintain the illusion of prosperity.

Of course, this can’t last, either. When his rather pitiful ruse is revealed, the neighbors prove all too ready to engage in some classic schadenfreude – the uniform has become a mark of disgrace rather esteem, and a nightmarish sequence of overlaid mocking faces and derisive laughter follows him. Perhaps everyone was waiting for this, after all … for the revelation that he is no better than them.

Of course, this can’t last, either. When his rather pitiful ruse is revealed, the neighbors prove all too ready to engage in some classic schadenfreude – the uniform has become a mark of disgrace rather esteem, and a nightmarish sequence of overlaid mocking faces and derisive laughter follows him. Perhaps everyone was waiting for this, after all … for the revelation that he is no better than them.

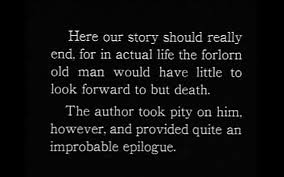

It’s a tragic story built out of the barest elements. Or it would be, if not for a ludicrously tacked-on happy ending, introduced with the following sardonic half-apology from Murnau, the only intertitle in a film that bravely (and remarkably) avoids the convention throughout:

So, rather than a tragedy, the film capitulates to what it expects an audience would demand, and we close instead with the doorman inheriting a fortune from a stranger. In case this were not heartening enough, Jannings doles out wealth to all the porters and washroom attendants, invites his old pal the night watchman to feast in the hotel, and even invites a tramp to ride off with him in a horse-drawn carriage. It’s wish-fulfillment on an almost comic scale, the sort of thing a child might imagine happening one day. (“But then he found a gazillion dollars and ate all the cake he wanted!”)

Of course, The Last Laugh didn’t make its mark on cinema history because of its thin narrative. It’s a spectacular visual accomplishment, embodying what would later be called “entfesslte Kamera” (unchained camera). Freund famously affixed the camera to his chest and bicycled through the set (notably, Murnau filmed entirely on sets, including the scenes in pouring rain). Another sequence was created by attaching the camera to a wire. Perspective is warped, with some camera movements played in reverse and structures towering above the doorman, conveying his psychological state. A memorable section visualizes his drunken state through in-camera tricks. Superimpositions abound. There’s a wealth of invention throughout the film, and a realized sense that Murnau and Freund were attempting nothing less than the invention of a purely cinematic language. It’s often thrilling.

And even though the narrative remains thin and its denouement fails as storytelling, there’s plenty of richness in its contours. As a reflection of Weimar anxieties, The Last Laugh is as evocative as Caligari or M. – there’s pessimism lurking beneath the splendor, a sense that stability is illusory and contingent, a class divide hiding in plain sight as the doorman tries, and fails, to straddle worlds.

And even though the narrative remains thin and its denouement fails as storytelling, there’s plenty of richness in its contours. As a reflection of Weimar anxieties, The Last Laugh is as evocative as Caligari or M. – there’s pessimism lurking beneath the splendor, a sense that stability is illusory and contingent, a class divide hiding in plain sight as the doorman tries, and fails, to straddle worlds.

There’s also the huge, looming import of the uniform. It is tempting to associate this, as Ebert himself does, with the coming rise of the Nazis – and there’s little doubt that the uniform is deeply fetishized in The Last Laugh. Like the black hand covering a map in Fritz Lang’s film, perhaps the uniform, as a locus of meaning and identity, signals the horrors to come. Emil Jannings, after all, would go on to a prominent role in the Third Reich, and from there to an eminently well-deserved position of universal scorn.

All of which is interesting but speculative. What’s clear watching Murnau’s masterpiece (one of his masterpieces, anyway) is that cinema, once it incorporated the film’s spirit of technical abandon and experimentation, would never be the same. Alfred Hitchcock, who apprenticed with Murnau, thought The Last Laugh a “nearly perfect film,” and a young Orson Welles was obviously paying attention – at least one shot in Citizen Kane is an outright homage.

Favorite Ebert quote:

His tragedy “could only be a German story,” wrote the critic Lotte Eisner, whose 1964 book on Murnau reawakened interest in his work. “It could only happen in a country where the uniform (as it was at the time the film was made) was more than God.” Perhaps the doorman’s total identification with his job, his position, his uniform and his image helps foreshadow the rise of the Nazi Party; once he puts on his uniform, the doorman is no longer an individual but a slavishly loyal instrument of a larger organization. And when he takes the uniform off, he ceases to exist, even in his own eyes.

Part of an ongoing effort to watch each of the films in Roger Ebert’s Great Movies series. The introduction and full list can be found here.