Every March, some folks over at Letterboxd hold a 30 Films In 30 Days From 30 Countries challenge, in which, unsurprisingly, you are challenged to watch 30 films in 30 days from 30 countries.

I’m giving it a go this year, though as you can see, I’ve already fallen behind schedule. I’ll occasionally cross-post these here throughout the month.

30 Countries in 30 Days #1: Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (Thailand, 201o)

There are moments in Uncle Boonmee which seem plucked from a much more interesting movie.

Unfortunately, the rest is a slow, exasperating march through magic realist tropes and the kind of extended takes that give “arthouse” a bad name. I actually had a pretty visceral feeling of irritation with it, but some of the images are definitely beautiful to look at.

#2: The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (UK, 1962)

Tom Courtenay’s Angry Young Man dominates nearly every frame of the film, scowling and smirking, playing the authorities for fools and waiting for his chance to undermine them.

The film definitely fits snugly in the British working class genre of its day — the cramped confines of shitty apartments, the offhand petty crimes and carousing of its misunderstood anti-heroes — but it’s Courtenay’s performance and the B&W, New Wave-ish cinematography that stands out.

I watched The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner in the context of comparing a bunch of “sports movies,” and that turned out to be an interesting lens to consider it through. Its aesthetic is obviously very much of its moment, but, as a film about “sport” in a general sense, it also features many recognizable aspects from that genre. Sports, first football and then track, symbolize different things for different characters here: an isolation and relative freedom for Courtenay’s Colin, who’s locked up in reform school; a means of success in the outside world for Michael Redgrave’s bourgeois Governor (but also a chance for his working class ruffians to stick it to the posh students and their coaches); and a mechanism for both social cohesion and individual rebellion, depending on where you’re seated.

Certain segments are edited to mimic aspects of the sport itself, or its individual affect on participants. The film flashes back to Col’s youth and all the things that led him here while he runs — the running itself seems a kind of meditation for him, or a way to reckon with the world. The freedom he finds in it is also reflected in a beautiful sequence when he is allowed to take off by himself through the forest, his pace and gait becoming a kind of solo dance number.

Those are just some of the interesting choices that director Tony Richardson and author Alan Sillitoe (adapting his own story) make. The combination of kitchen-sink realism and anti-hero sports story is a pretty fascinating one.

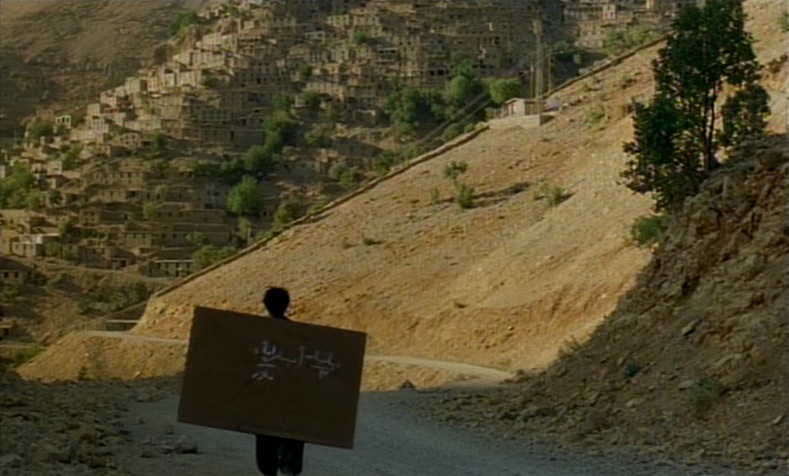

#3: Blackboards (Iran, 2000)

Samira Makhmalbaf’s portrait of wandering Kurdish teachers, seeking pupils in the mountains near the Iran-Iraq border during wartime, plays out like a fever dream. And like a dream, it’s fascinating, allusive, and occasionally boring.

The title refers to the blackboards these men carry on their backs, as they go around trying to find a school in need of a teacher or a pupil who can pay (if only in food). These blackboards serve double, triple, quadruple duty — they are for instruction, to provide shade from the elements, to shield members of the groups from gunfire, to carry and assist the wounded, and more. “Blackboards” are a free-floating metaphor throughout, a literal blank slate covered with attempts at instruction and then washed clean with water, or covered in mud to provide camouflage.

Makhmalbaf has things to say here, largely about the relative value of contemplative learning in a world where it’s impossible to sit still. But the film’s insistence on repetition of phrases, underlining of previous conversations, and the ways in which the teachers wear down everyone else in their vain attempts to impart knowledge that the pupils really don’t have time for ultimately become tiresome.

On the other hand, the location shots of the mountainous region are often stunning, and there’s sly comedy and some solid performances amid all the haranguing, shouting, and preaching.

#4: Our Neighbor, Miss Yae (Japan, 1934)

A charming slice-of-life picture, introduced with an impressive lateral tracking shot that places us as viewers solidly in the middle-class world of our protagonists. It also demonstrates right away that this will not be an epic, or a story of samurai, or a grueling melodrama.

Instead, Our Neighbor, Miss Yae is a story of regular folks living regular lives, of teenage longing and middle-class striving, of changing norms for women in society, of the pleasure of a day spent with friends at a movie theater in the city. It’s almost entirely without incident — unless you count a baseball breaking a window — but never slow.

In short, it’s charming as hell.

(Full review, as part of the Counter-Programming series, here.)

The word “oneiric” is clumsy and almost always a little irritating, but it fits Embrace of the Serpent well. This is a dreamlike passage down a river and through time, occasionally punctuated by bracing (and surreal) moments of colonialist violence. Fans of Apocalypse Now and Aguirre, its clear touchstones in many ways, will admire it, but I think it would be reductive to just leave it with those comparisons.

Embrace aims at something more mystical and allusive, while still pulsing with anger at the despoilment of the world. It’s structured around two stories running in parallel, about people who are the same and yet different, and it all comes back around, eating itself by design. It’s a gorgeous and unique film.

(Also: I feel lucky to have seen it on a screen, and if you can, do that. The images alone are worth it.)

The plus-side: It’s endlessly inventive. The down-side: it’s kind of exhausting. Maddin’s trademark infatuation (bordering on fetish) for early film is on elaborate display here. So are the jokes: compared to My Winnipeg, Brand Upon The Brain, and the shortThe Heart of the World, which are the others I’m most familiar with, The Forbidden Room is fucking hilarious.

There are jokes aplenty in the other ones, but the very nature of this movie — tiny featurettes created from lost silents and rumored titles, not so much strung together as stuffed inside of each other narratively, like Russian nesting dolls — is funny.

We open in a submarine where people are eating flapjacks to survive, because they have little air pockets. A woodsman knocks on the door. (Yes, the submarine door.) He tells his story to the bewildered submarine crew, but that story gets interrupted by another, and that one by another, and another. There are kidnapped maidens, thieving cave-dwellers, men who can listen to the snow, a musical interlude about guy who gets brain surgery to remove his obsession with butts, an amnesiac. This goes on for so long that the film finally has to resort to a “Book of Climaxes” at teh end to sort everything out. And it still doesn’t mean anything at all.

Maddin, the most mild-mannered guy around, is an anarchist of a filmmaker, part Situationist insurrectionary, part post-Freudian prankster, and part little kid playing with pictures on the floor.The Forbidden Room might be a bit too up its own ass for its own good, but Maddin certainly didn’t take any half-steps.

This is an absurdist tale of the future, aggressively (and humorously) presented in the vocabulary and grammar of cinema’s past, and if I’d seen this last year, it would’ve probably topped my list. It’s every movie, real or imagined, as filtered through a very unique sensibility.

In short, I like this weirdo movie very much.

Of all my oddly and accidentally surrealist “March Across The World” choices, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is the most pure so far in its dream-like aesthetic.

A coming-of-age story taking place (maybe? maybe?) in the unconscious, slightly-askew Czech New Wave auteur Jaromil Jires draws on fairy tales, vampire myths, and apparently deep wells of angst about incest. It’s impossible to say what happens and what does not: the mundane and the magical overlap consistently, and it’s not even clear what time period we’re visiting.

Such as it is, Jires tells the story of young Valerie, a wide-eyed and oddly beguiling 13-year-old who has just got her period (memorably represented with drops of blood on a daisy, as in the picture used here). She then floats through a series of adventures involving young love, vampires determined to steal youth, clerical corruption and pedophilia, witches burned at the stake, enchanted earrings, forest-based orgies, and so forth.

Valerie, to her credit, takes it more or less in stride, which is probably good advice for the viewer, too. This is less allegory than collision of sensibilities and images, many of them extraordinarily beautiful and many of them confounding … which is actually a very good way to depict growing up.

It’s also the first and only Macedonian film I’ve ever seen, so I don’t have much to compare it to on that score. But at its heart, it’s the kind of elliptical and sorrowful film that places you right in the middle of its absurd confrontations and moral ambiguity.

There are three central stories — a young monk shielding an Albanian girl on the run, an English reporter covering the events in the region, and her sometimes-lover Alexsander, a war photographer returning to his village in Macedonia for the first time in more than a decade. Manchevski arranges the narrative in a set of three, and then skews them, playing them against each other and juggling time and incident in ways that suggest this may go on forever, or it may be possible to end it tomorrow. The film makes no argument one way or the other.

Rade Serbedzija, as the emotionally-wounded Alexsander, makes the biggest impression, but the cast is full of well-chosen faces and presences. “Before The Rain”, the title, refers to a moment full of possibility, promise, and danger, and Manchevski literalizes it a bit much by the end.

But this imagistic vision of a world coiled around itself, and its people stuck in loves and antagonisms almost beyond their control, lingers after its done.