Part of an ongoing effort to watch each of the films in Roger Ebert’s Great Movies series. The introduction and full list can be found here.

“A text could be written about the impact of Pastrone’s experiments in lighting and camera movement, decisive in freeing the movies from the proscenium.”

~ Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times (quoted at the beginning of Kino Video’s restored Cabiria)

“Proscenium” is a word I was unfamiliar with when it appeared on the screen during my first viewing of Cabiria. It refers to “the part of a theater stage in front of the curtain.” So Thomas’ point is clear: Pastrone’s 1914 Italian epic (and I do mean epic) landmark marks one of the earliest attempts to chart a vocabulary and approach distinct from theater and opera, to create a film that draws from those traditions but is uniquely “a film.” There are moments over the course of its 2-hour-plus running time that it succeeds wildly, and other moments when the struggle between forms, or of a new form fighting its way into the world, is clear as day. It’s a fascinating tension, and a gripping experience.

Cabiria is epic in every way: in its scope, its setpieces, its ambition. It aims to tell both the entire story of the 3rd c. (BC) Punic Wars through the eyes of multiple protagonists, as well as chart their personal journeys and struggles, and to do so by making use of the new opportunities film presents.

We escape volcanic eruptions, walk through the gaping and terrifying mouth of an entrance to the staggering Temple of Moloch, climb mountains, scale fortified walls, trudge through gorgeously shot deserts. There are adventures galore, and cruelty, greed, the elaborate death throes of suicide by poison, mercy, and love. Pastrone seems intent on providing both the intimacy and heightened emotion of the stage with the grandeur of natural locations and wide shots of a cast that must rank in the thousands.

Our story begins one lovely, sun-lit morning in Sicily, on a palatial estate. Young Cabiria and her nurse play with toys on the lawn while servants start their day’s tasks. The eruption of Mt. Etna disturbs this, and the ensuing destruction (incredibly rendered, in ways I still can’t figure out exactly) destroys the home. Cabiria is presumed dead in the rubble.

Actually, she is spirited away by the fleeing servants. But, as usually happens when fleeing volcanic eruptions (if my experience is any guide), all are caught by Phoenician pirates, and sold into slavery in a Carthaginian marketplace. Cabiria is destined for human sacrifice to appease Moloch, the God of Bronze. (Alongside the servants pausing to collect as much treasure as they can carry, putting everyone’s lives in danger, this is an early note of the prominence of greed in the story. And not the last one.)

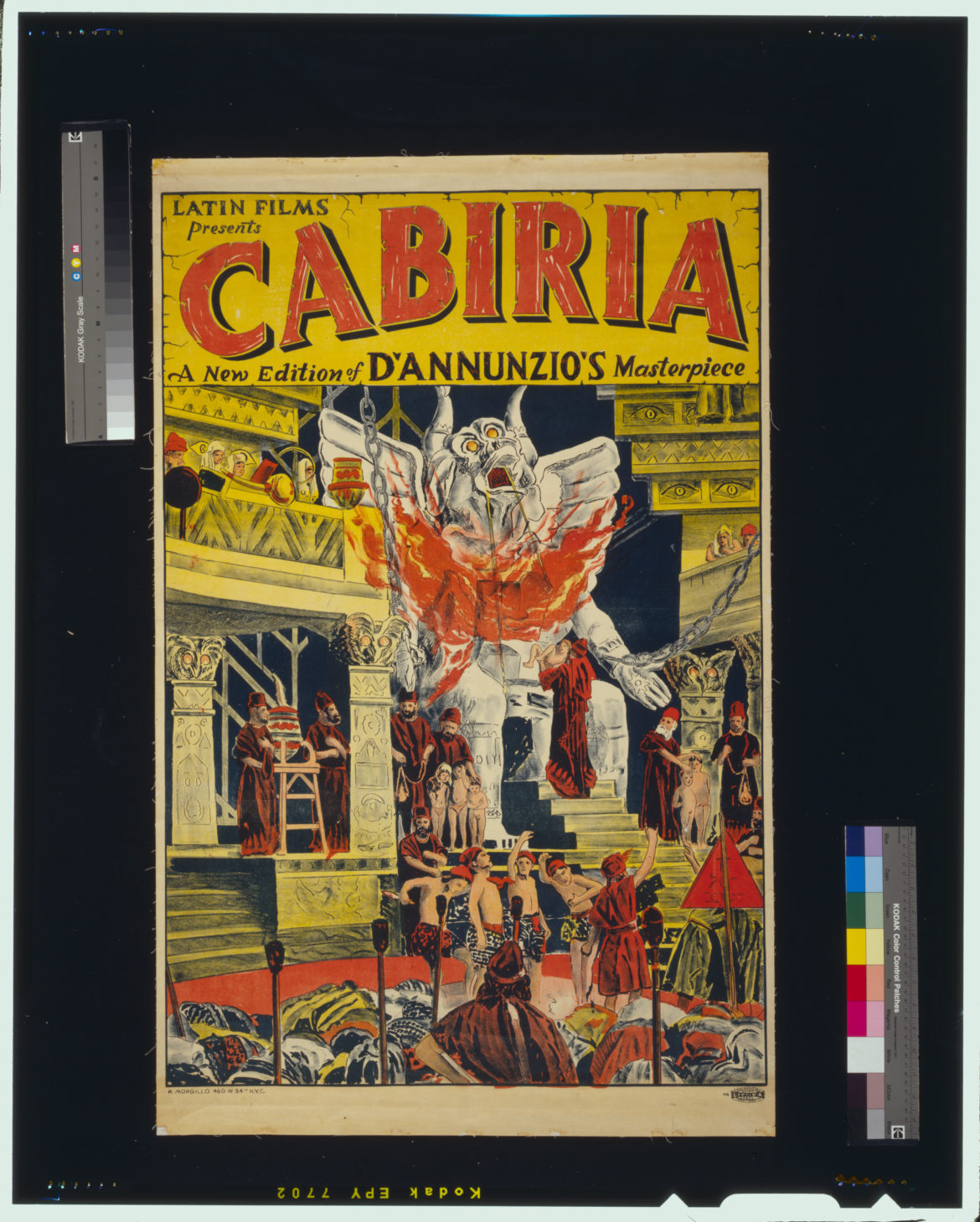

She is only one of the “100 innocent children” destined to be burned alive to curry favor with the divine. The scene in the Temple of Moloch is legitimately terrifying and completely surreal. The masses head into the temple through a gaping mouth set in stone under a bright, sunny sky; inside, it’s mostly lit by flames held aloft, and the sacrificial fire that is set inside a huge stone idol/crematorium. Priests and others hold up strange, oversized fake hands, palms upright, and Pastrone holds the shot – we are left with the flicker of fire and the unnatural appendages. It’s incredibly disconcerting. One by one, naked, resisting children are fed to the flames, the aperture closing behind them and then smoke emanating from the god’s stone head. These grim proceedings go on for several minutes, far longer than I would’ve expected audiences to tolerate in 1914. Or now — It’s as scary as anything from a modern horror film, and scarier than most.

But not to fear, too much. (At least not for Cabiria – pretty sure 99 naked children were burned alive, but let’s not dwell on that.) Through a series of stagy interventions, Cabiria is rescued by the Roman Fulvilo Axilla and his faithful “servant” (that means “slave”) Maciste, an improbably muscular, Johnny Weismuller-type who later even climbs a tree limb and swings on a rope. Escape is short-lived, however – the trio is split up in the ensuing chase, and each must find their own way. Some are captured, some manage to flee to fight another day.

There are reconnections between them, but the film then shifts from the personal to the political. The machinations of war grind on, in ways too complicated to go into very much, and our focus seems to shift to Fulvilo and Maciste more than Cabiria, which is sort of odd in a movie called Cabiria. And then to the leaders of Carthage, Rome, and elsewhere, and court drama behind them, and proto-femme fetales in a vaguely Cleopatra mold. Pastrone’s epic intent, and his uneasy update of Shakespearian history tropes to the screen, are clear in some of the almost hilariously wordy intertitles that serve as awkward exposition. Here’s a favorite, which introduces Episode 6:

Syphex, King of Cirta, has stripped Massinissa of his realm. Massinissa has vanished into the desert. Hasdrupal gives his daughter, Sophonisba, to the more powerful suitor and secures from this aging son-in-law an alliance against Rome.

Got that? Good.

And that’s not even a particularly confusing one. Viewers might want to bring a list of characters to the film – it approaches Pynchonian levels at points.

The intertitles deserve some mention themselves, as they might be the most evident aspect showcasing the tension between the stage and early cinema. While later silents – like those of Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, or Charlie Chaplin – would work to make the action and motivation apparent on the screen with minimal overlaid text, rightly figuring people weren’t coming to the movies to read, Pastrone did not. (There are also virtually no close-ups on faces, a defining feature of “later” early cinema.)

Introductory text explains every scene, as though the filmmakers were nervous audiences simply wouldn’t understand the goings-on through image alone. On the one hand, this can be kind of annoying to modern eyes (mine, anyways). On the other hand, they provide a wonderful test of Ebert’s maxim that “It’s not what the movie is about, but how it’s about it.” Since you know going in what will occur, more or less, you’re somewhat freed to examine how it occurs. This has nothing to do with Pastrone’s intention and everything to do with how we watch movies, but it’s pretty interesting. He also manages some quite witty moments: a title card that reads “Maciste convinces the innkeeper” is followed by Maciste grabbing the innkeeper by the collar and thrashing him a bit, which is pretty funny. That’s one meaning of “convince,” I suppose.

Those intertitles are also flowery to a degree most would find absurd now, but suggest Pastrone and others wanted to connect their film to previous traditions that contemporary audiences might know and relate to. There are many examples, but I loved this exchange, between a woman of privilege and her attendant, about the guy who just sent her an invitation to meet for a tryst in the woods:

– What is he like? Tell me?

– Like the spring wind that crosses the desert on feet of clouds bearing the scent of lions and the message of Astarte!

I don’t even know what the message of Astarte is, but I was hoping she’d reply, “So, he’s hot, then, I guess?” Unsurprisingly, this is not the direction things headed, but definitely showcases the lyrical sensibility that guides the film’s approach.

As the film goes on, the epic aspects increase – battles are fought, kings are captured, armies surrender, towns are sacked. But the main interest here is how the technique reflects the interests of the time, and how it points to future developments.

According to that Kino Video prologue, D.W. Griffith was so struck by Cabiria that he radically changed the project he was working on, which would be released as Intolerance. I’ll be watching that in coming weeks, but what’s clear from Pastrone’s film is how the camera itself is coming into play, and how lighting affects scenes and suggests character’s states of mind. It’s staggering: there are shots that seem to have crawled off the wall of a gallery.

And there are sequences that are startling in their forward-thinking technique. One to cite, in particular: in Episode 6, a steady shot is held from close to the street as one of the main characters approaches, and he, obviously, increases in size until he comes to loom over the viewer, suggesting authority and swagger. As he walks away, headed towards danger, his figure, obviously, diminishes, until it’s just his feet and those of his companions we see in the distance. The camera doesn’t move in these shots, just observes, but you get the sense of power in the first shot, resignation and danger in the second. It called Kurosawa immediately to mind. Which is to say, it brought cinema to mind.

Other scenes play with natural light (much of the film is shot outside, again diverting from the confines of the stage). They hide characters in the shadows while others are fully illuminated. We watch the sun fade over the desert and the slow motion of people across it. Pastrone’s intent couldn’t be clear if he actually put up text saying, “This is a movie, everybody. Movies could be a thing, and different.”

The film ends on a triumphant note, affirming Rome’s supremacy over the all the people of the world (er…) and the power of love (aw…). The film’s release came on the heels of Italy’s victory in the Libyan War of 1911-12, and it’s one of many epics produced just prior to World War I (which, I wager, might have sapped some of the enthusiasm for violent historical epics out of the movie-going public, at least for a little while). That might be a dreaded “extra-textual,” but it helps explain why Pastrone, in 1914, wanted to make a film about the triumph of Rome in the 3rd c.

But Cabiria is anything but a history lesson on the Punic Wars. (For one thing, I don’t think Archimedes constructed a huge mirror to blow up enemy ships using the power of the sun. Correct me if I’m wrong.) That’s one aspect, but it’s also about the tragic collision of doomed lovers, the moral corrosion of power, the omnipresence of greed, and the redemptive elements of love and mercy.

More than anything, though, it’s about how to use cameras, light, darkness, imagery both surreal and naturalistic, and episodic, cross-cut storytelling to distinguish film from other media. Its real legacy is the very idea that captured images can be arranged to delight and amaze, that this sort of magic is possible. For all the merits of the stage, you can’t actually trudge through the mountains, or construct a half-pyramid shape with actor’s shields to climb the walls of a fortified building while things are on fire, or cast 1,000 people to mount a battle in a wide-shot.

That’s a job for a different medium, and Pastrone was trying to figure out how it worked. He was enormously successful.

Ebert’s review is here. Favorite line:

What we are now beginning to realize, as more silent films are rediscovered and restored, is that no one film was a breakthrough but excitement and innovation were everywhere in the air; since films from all nations could play anywhere just by changing the languages of the title cards, what directors learned from Sweden tonight was in the films they were making tomorrow in Italy or America.

Next up: Birth of a Nation. Oboy.