“I guess I wasn’t built for this.”

“Nobody was. It’s all just a trick we perform, when we’d rather not die immediately.”

Stanley Kubrick’s first feature Fear and Desire – famously considered lost for years, and famously dismissed by Kubrick himself as “a bumbling amateur film exercise” – is an existentialist war movie. And, with all due respect to its creator, it’s a kind of masterpiece.

There are hints at future Kubrick efforts throughout, especially Paths of Glory (and, to a lesser extent, Full Metal Jacket). Yes, it is over the top and enamored with its own insights in the way only the works of young artists can be. Yes, the performances are broad, and the whole thing is ostentatiously, sometimes clumsily shot. It is clearly the work of a young photographer-turned-director finding his footing. But in its focus on two unnamed countries at war, its stated insistence in the opening narration that the events exist “outside history” and that its characters’ “have no country but the mind,” and in its final reveal, Fear and Desire has an ambition that far outstrips its tiny budget and related shortcomings.

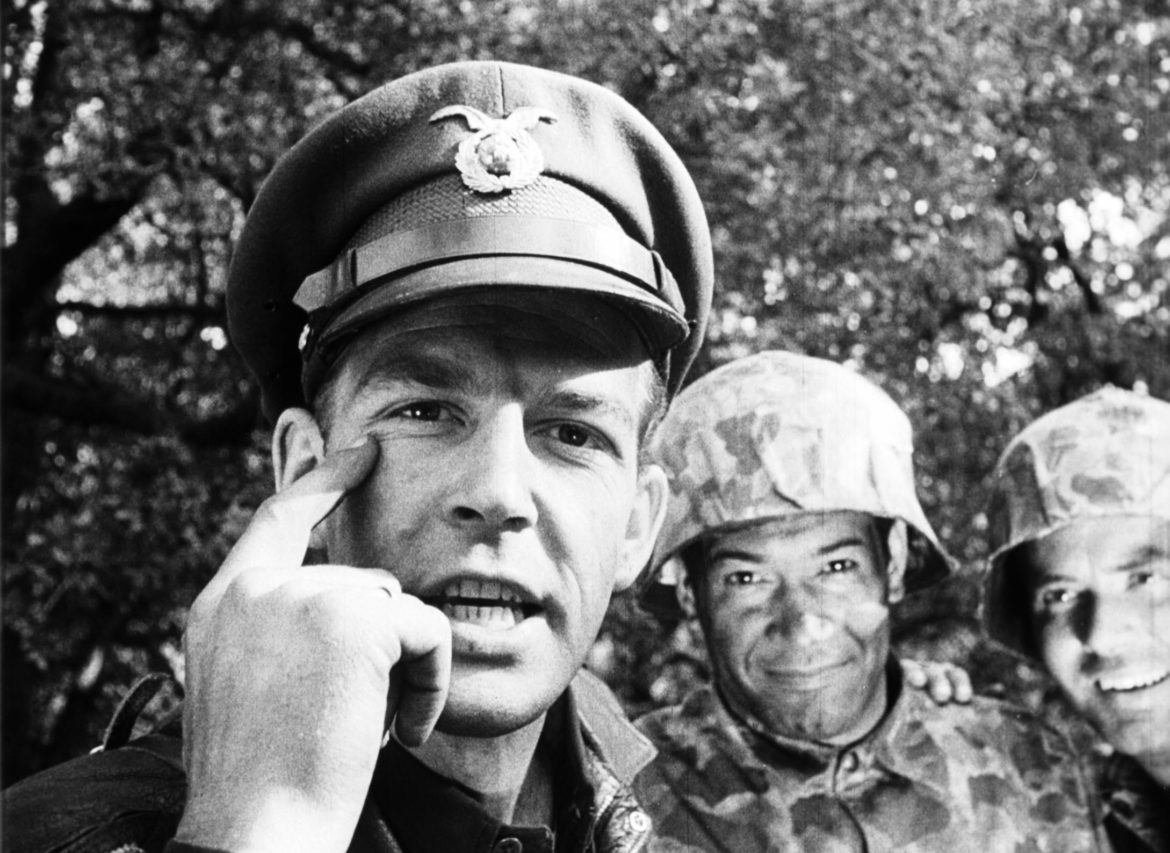

From the start, the film takes place in a nowhere space. Fog constantly obscures the wide shots. Shadows abound. Close-ups, which show all the hallmarks of Kubrick’s career as a photographer, seem to expose every pore on faces, but bring us no closer to these characters as individuals. Our four protagonists are clearly American (they wear recognizable camo uniforms and get dickishly frustrated when others don’t speak English) but that’s about the only signpost.

More an archetype or fable than anything else, the film comes on like some sort of wartime Godot: the central characters are behind enemy lines (whoever the enemy might be) and cut off, trying to make their way back down the river and out of danger, and in the meantime mostly grappling with the absurdity of their situation. At least one goes mad.

In their effort to escape danger, the crew comes across a peasant woman returning through the woods, and ends up tying her to a tree lest she reveal their position (there are brief suggestions of a kinkier subtext here, but the film doesn’t belabor the point). She’s entrusted to Pvt. Sidney (future director Paul Mazursky, who passed away last year); the private takes the opportunity to speak endlessly at her, pouring out his anxieties, mounting dread, and plaintive desires, despite her inability to understand a word of what he is saying.

Meanwhile, the rest of the crew works on putting a raft together to float out of danger. Once they discover an enemy General is close by – how many times do you get the chance to kill an enemy General? – the plan shifts. Its last moments argue that the “country of the mind” in which they find themselves might be theirs and theirs alone.

Aside from the climactic raid on the General’s camp, there’s little more to the story than that. Clocking in at almost exactly an hour, it has the air of a glorified short as much as a feature. Like Paths of Glory and Full Metal Jacket, there is a deep skepticism of war in and of itself – its absurdities stand in for the impossible relations humans have with each other and ourselves more generally. (It’s hard not to read the title echoing Kierkegaard’s foundational existentialist work “Fear and Trembling,” another account of a world that demands action while withholding any guidance on how to act.)

Unlike those later films, Fear and Desire is a full-on dreamscape, or, if you like, a nightmare. It’s not hard to see why the notoriously perfectionist Kubrick distanced himself from it further on in his career – it’s hardly subtle, and, while the low budget led to inspired improvisation (reportedly, tracking shots were done simply by affixing the camera to a baby carriage), it lacks the formal grace that we generally mean when we say “Kubrickian.”

But many of the later hallmarks are here, in sometimes staggering form, right out the gate. The photo-realism and composition of the shots stand in contrast to the eerie atmosphere and sense of inescapability, and its philosophical bent makes it completely compelling. Three years later, The Killing would remap these themes through the vocabulary of film noir; 27 years later, a very similar set of themes would emerge in The Shining, one of the most accomplished horror movies of all time (no matter what Stephen King thinks).

Fear and Desire might not live up to later Kubrick’s standards, or the standards of later Kubrick films, but so what? Little else does, either. It’s not only an incredible debut, but a striking exploration of what it means to exist.