We are familiar with the “making-of” documentary, but Sandi Tan‘s Shirkers turns it inside out. This is a “losing-of” documentary — a relentlessly charming love letter to indie cinema and its irrepressible DIY spirit, but also a confounding psychological mystery that asks, “How do you represent a film that exists almost entirely in memory?”

The film in question was meant to be titled, like its decades-later doppelganger, Shirkers. A metaphysical ghost story / revenge narrative / road movie written by and starring Tan, and filmed in an early 90s Singapore that wasn’t exactly a haven of filmmaking, independent or otherwise, Shirkers was not so much “lost” as “absconded with.”

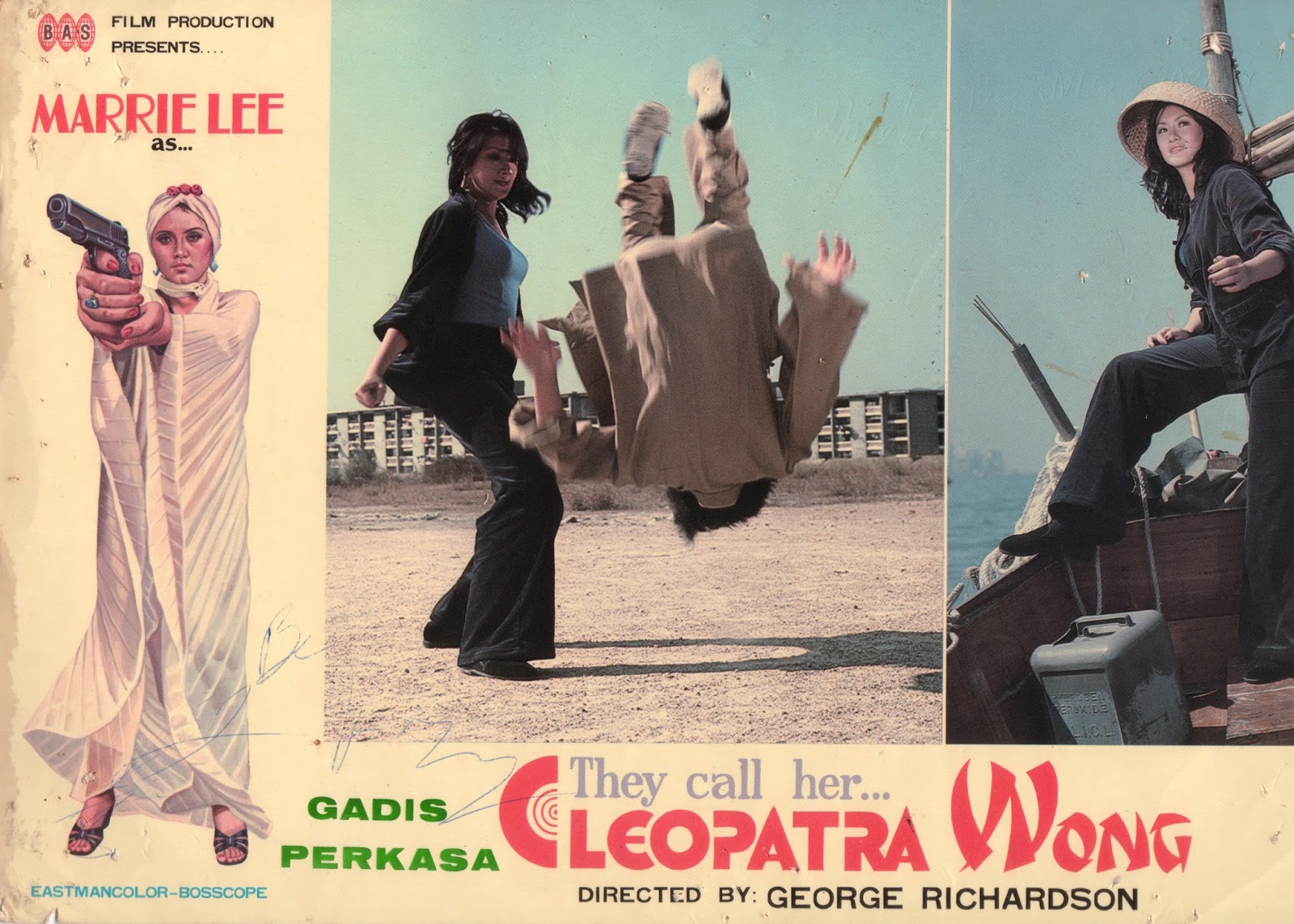

For a variety of reasons, Singapore has not historically been known for its cinema, certainly not its home-grown productions. With the notable exception of They Call Her Cleopatra Wong, a 1978 martial arts / distaff superspy flick self-consciously reworking the Blaxploitation of Cleopatra Jones for local audiences, there are very few touchstones after the industry declined post-Independence in 1965. (Wikipedia’s “List of Singapore films by year,” for example, collapses the 1920s – 1990s into a single category.) Shirkers might’ve changed that, or at least marked an early explosion of rebellious energy, had the reels not been stolen by a sinister, charismatic international man of mystery named George Cardona. Cardona — who represented himself as a filmmaking mentor and well-connected old hand, and even dubiously bragged that he’d been the model for James Spader‘s character in sex, lies, and videotape — was Shirkers‘ erstwhile director. He zealously coached a group of Jarmusch-and-Varda-loving teenagers into making their road movie passion project, and then vanished with the footage, like a total, absolute weirdo.

For a variety of reasons, Singapore has not historically been known for its cinema, certainly not its home-grown productions. With the notable exception of They Call Her Cleopatra Wong, a 1978 martial arts / distaff superspy flick self-consciously reworking the Blaxploitation of Cleopatra Jones for local audiences, there are very few touchstones after the industry declined post-Independence in 1965. (Wikipedia’s “List of Singapore films by year,” for example, collapses the 1920s – 1990s into a single category.) Shirkers might’ve changed that, or at least marked an early explosion of rebellious energy, had the reels not been stolen by a sinister, charismatic international man of mystery named George Cardona. Cardona — who represented himself as a filmmaking mentor and well-connected old hand, and even dubiously bragged that he’d been the model for James Spader‘s character in sex, lies, and videotape — was Shirkers‘ erstwhile director. He zealously coached a group of Jarmusch-and-Varda-loving teenagers into making their road movie passion project, and then vanished with the footage, like a total, absolute weirdo.

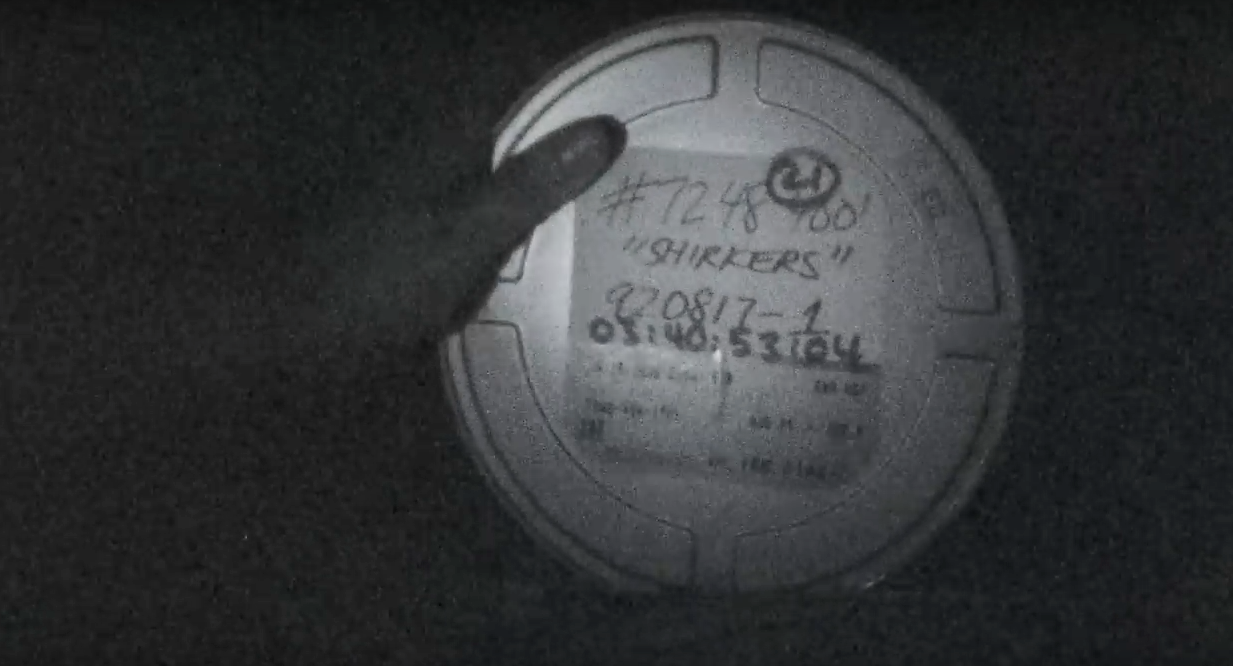

Tan’s documentary is an evocation of the time, place, and people involved in this oddball story, and also something of a necromancy. After Cardona’s death decades later, his widow gets in touch; Shirkers lives! The complete reels of film, minus the sound, had been kept and preserved over the years, transported obsessively between the houses and countries where Cardona had lived in the interim, along with an alarmingly meticulous collection of Shirkers ephemera. He’d somehow appointed himself sole curator of the world’s most bizarre personal archive, like a mythological creature hoarding other people’s memories.

Tan’s documentary is an evocation of the time, place, and people involved in this oddball story, and also something of a necromancy. After Cardona’s death decades later, his widow gets in touch; Shirkers lives! The complete reels of film, minus the sound, had been kept and preserved over the years, transported obsessively between the houses and countries where Cardona had lived in the interim, along with an alarmingly meticulous collection of Shirkers ephemera. He’d somehow appointed himself sole curator of the world’s most bizarre personal archive, like a mythological creature hoarding other people’s memories.

Why would he do this? Shirkers, and Tan, try on some answers for size — To sabotage success he could never obtain personally, a pattern other Cardona acquaintances recognize? To wield some kind of fetish power? Did he envision editing and releasing the film himself? — but nothing really fits. Cardona’s motivations remain as absent as the location recordings he pointedly trashed. The whole situation has a strong sense of abuse — the age and power differences; recollections of his increasingly controlling, occasionally outright suspicious behavior during production; sending, as his final gesture of post-Shirkers contact, dummy videotapes full of snow in lieu of the footage, like a serial killer without the killing or a bizarro James Spader — and Tan seems to feel that something, an innocence or trust, was indeed stolen along with her movie.

We are left with a triple absence, in the form of a movie that never was and a man it is nearly possible to situate in a country that has changed dramatically since Tan’s cameras captured its storefronts and countrysides. Shirkers, the documentary, is not simply Cardona’s story, as creepily compelling as it is. It’s also the road movie — its unspooling, indeterminate structure emphasized with experimental manipulations and complex textures in the sound design — that Tan never got to release, an excavation of memory and an occasion for reunion. Her Shirkers compatriots Jasmine Ng (with whom Tan endearingly pledged to form “the Coen Sisters” back in the day) and Sophia Siddique are on hand to give their takes, which range from lingering bewilderment to bemused grievance; the two are, respectively, a filmmaker/activist and the chair of Film Studies at Vassar. Their Shirkers is a flickering, cinematic bond between the three, made of fugitive stills.

We are left with a triple absence, in the form of a movie that never was and a man it is nearly possible to situate in a country that has changed dramatically since Tan’s cameras captured its storefronts and countrysides. Shirkers, the documentary, is not simply Cardona’s story, as creepily compelling as it is. It’s also the road movie — its unspooling, indeterminate structure emphasized with experimental manipulations and complex textures in the sound design — that Tan never got to release, an excavation of memory and an occasion for reunion. Her Shirkers compatriots Jasmine Ng (with whom Tan endearingly pledged to form “the Coen Sisters” back in the day) and Sophia Siddique are on hand to give their takes, which range from lingering bewilderment to bemused grievance; the two are, respectively, a filmmaker/activist and the chair of Film Studies at Vassar. Their Shirkers is a flickering, cinematic bond between the three, made of fugitive stills.

It’s tempting to clamor for the reconstruction and “re-release” of Shirkers, the enigmatic road movie, now a silent (or, as Tan puts it, “rendered mute.”) What we see of the footage is intriguing: it could be lyrical, post-punk outsider art, wearing its color-saturated heart on an absurdist early-90s Singapore sleeve. The Tan who comes across in the documentary seems unlikely to make that film now, though. Her interrogation of Shirkers and its ghosts is more interesting anyway. It is Shirkers, and we’re lucky to have it.