Kaneto Shindo was a remarkably prolific writer and director who dabbled in numerous genres. His horror Kuroneko (full translation of the original title: “Black Cat from the Grove”) is a surprising, eerie film, shot in haunted black and white by frequent collaborator Kiyomi Kuroda, that draws together elements of Japanese folklore and period setting with very modern sensibilities – a disdain for authority and tradition, a Freudian uncanniness, a clear attention to the plight of “commoners,” and a feminist edge.

Kuroneko shares much with other interrogations of samurai culture and myth more generally (like Shindo’s Japanese contemporaries, and also like the revisionist American Westerns of the same period), but it also resembles the creepy melodrama of classic Hollywood horror and points toward the violent revenge narratives of exploitation.

I knew none of this going in. I only knew that it’s a title which shows up on a lot of “important horror movie” lists. (I’ve since seen his Onibaba, which draws on the same myth to construct a very different story.) So the opening sequence – which, it should be noted, could be triggering to those who have experienced sexual violence – was pretty jarring. It’s not “I Spit On Your Grave,” but it was a lot more intense than I expected.

A group of 20-some samurai, famished from the road and far from their leader’s sight or their community’s awareness, emerge from a wooded area like a fog, like they are part of the landscape itself. They break into a secluded home occupied by a woman and her daughter-in-law, pillage their house for food and drink, rape them, and burn the house to the ground with the women inside, then fade back into the forest.

The images of different samurai grotesquely eating food with their mouths open while others assault the women are horrific, but make one thing very clear: these are not the noble warriors of myth, fighting for the common man and woman against lawless bandits. It’s an inversion of that mythology, and probably far closer to the truth of life on a battlefield in any country at war than the comforting stories of heroism we like to tell ourselves.

The women’s bodies lie, strangely intact, on the ashes of their destroyed house. A black cat walks between them, meowing, gently licking their faces. This at first seems forlorn – the cat has been abandoned, its loving keepers defiled and killed. Then the camera focuses on the cat lapping directly from their wounds. That forlornness is replaced with something eerier, and you wonder why it is, exactly, that their bodies weren’t engulfed in the fire.

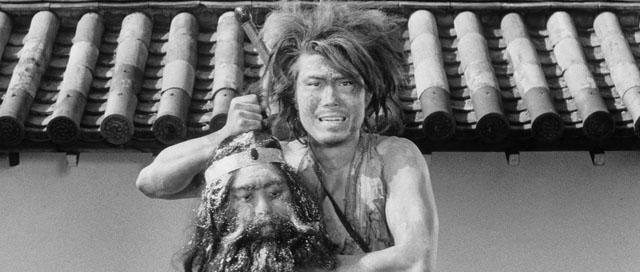

Samurai start dying near Rashomon Gate, found with their throats ripped out and wounds that seem to be made by claws. A woman in white, shrouded in the darkness, asks men for help getting across a particularly shadowy and dangerous road, invites them to the secluded house she shares with her mother, gets them drunk, entices them to bed, and kills them in the heat of passion, drinking their blood from the neck. The emperor is displeased with the mysterious deaths – it’s implied that they tarnish the image of the all-powerful samurai warrior, which is unacceptable – and tells the local leader to put an end to this embarrassment.

We discover that the two women from the beginning of the film had been waiting for a man named Hachi to return – son to one, husband to the other – who was conscripted into battle from the fields he was working, and it was in his absence that they met their horrible fate. Now, they’ve been granted extended life by powerful forces, contingent on them exacting vengeance on all samurai. Hachi does return, after three years. But now he too is a samurai, with a new title bestowed, somewhat cynically, on him for battlefield bravery. He’s asked to deal with the ghostly murders, and ventures into the mist and the woods …

It’s a familiar enough tale, but one that turns in on itself, with tragic implications for all involved. The horror is in the sense of inevitability, as it is in all tragedy – of course it would be this way. Shindo’s approach to these stories – the way in which he ties together different traditions and senses of the uncanny – is what gives the film its resonance, along with the stunning cinematography and believable characters.

This is all paired with a deep distrust, on the film’s part, of those in charge, not just the lower-level functionaries committing atrocities when no one is around. This distrust even extends to the stories they tell: Raiko Minamoto, the grand leader in this corner of the forest, tells Hachi they will embellish his exploits for the common man, as he has done with his own in the past, so that they will be thought all the more heroic, and consolidate power in their realm. He is both contemptuous of the commoner, who he rather dramatically deems “unfit even to live,” and at the same time oblivious to the larger forces at work that mock his petty aims and delusions of grandeur.

With this angry swipe, Shindo announces that Kuroneko is definitely a ’68 film. In an interview accompanying the Criterion version, he isn’t comfortable calling himself a Marxist, but says, “I am a believer in socialism … If you have to look at society through the eyes of those placed on the bottom level, you cannot escape the fact that you must experience and perceive everything with a sense of political struggle.” His Kuroneko is a creepy, accomplished, sly movie that should be more widely known than it is.