May 1968 looms so prominently over the cultural imagination, at least in some circles, that the occasion of its 50th anniversary was bound to produce a universe of responses and treatments. Its ecstatic title notwithstanding, João Moreira Salles‘ essay doc In The Intense Now falls decidedly onto the elegiac side of things.

The film takes a broad view, weaving the Parisian events of May into savvy, found-footage glimpses of Prague and his own mother’s trip to China two years prior. This widens the poetic scope of the film’s concerns. Even in its deep dive into the images that came out of Nanterre, Salles’ depiction goes out of its way to avoid hero-worship, and manages to do so without trafficking in embarrassing deflationary pastiche or cutesy callback (we have Michel Hazanavicius for that, God help us). But In The Intense Now goes almost too far into sorrow: contra its title, these images, resonant of fleeting glory, are presented as graffiti from an impossible yesterday. No one needs more ’68 riot-porn, but still: this is one remarkably despondent portrait of joy.

As a lyrical treatment of a tumultuous time, though, the film often succeeds in transporting the viewer, making unexpected connections that diverge from your standard barricades-and-pranksters portraits. In The Intense Now is at its best when zeroing in on specific fragments, usually culled from the archival material. The images of a family in a Czechoslovakian home movie are read — by their clothes, countenances, placement within the frame — for commentary on social and class conditions. Footage shot surreptitiously from an apartment window reveals the unseen dangers on the Prague street that drove the anonymous videographer upstairs, to film his or her own city like a spy. The joy evident on his mother’s face in China tells more about her life and its dwindling moments of possibility than it does about the Cultural Revolution she fails to see transpiring in the background.

As a lyrical treatment of a tumultuous time, though, the film often succeeds in transporting the viewer, making unexpected connections that diverge from your standard barricades-and-pranksters portraits. In The Intense Now is at its best when zeroing in on specific fragments, usually culled from the archival material. The images of a family in a Czechoslovakian home movie are read — by their clothes, countenances, placement within the frame — for commentary on social and class conditions. Footage shot surreptitiously from an apartment window reveals the unseen dangers on the Prague street that drove the anonymous videographer upstairs, to film his or her own city like a spy. The joy evident on his mother’s face in China tells more about her life and its dwindling moments of possibility than it does about the Cultural Revolution she fails to see transpiring in the background.

This tendency, and the film’s relentless melancholy, is encapsulated by Salles’ examinations of France. First, a wonderfully presented bit of footage depicts an attempt by the students to connect with Renault factory workers. The workers, who vocally consider these anarchists their future bosses, are seen above, lining an implacable wall, with the students in the street below, preaching revolt. They are literally on uneven ground.

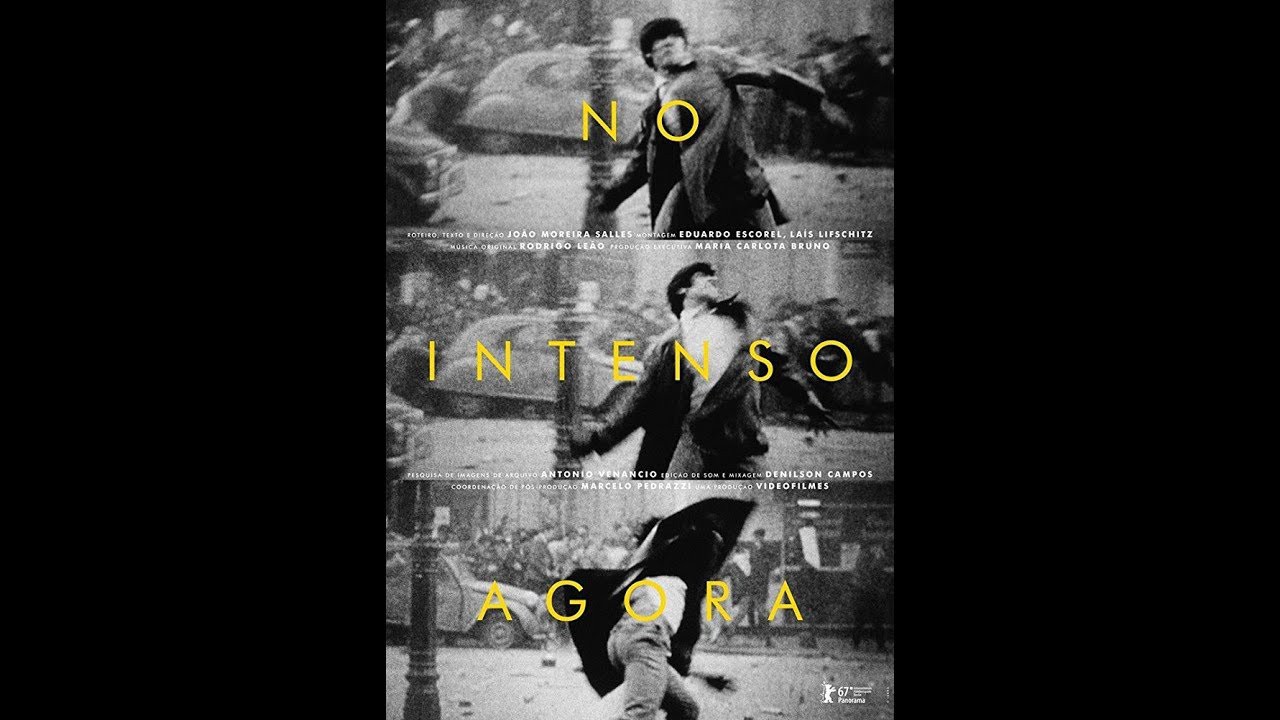

And then there is the famous image of the Parisian protester hurling a stone; you know the one. It adorns every depiction of the events of May, carried down to us by screenprints, Banksy, and, inevitably, the promotional materials for In The Intense Now itself. Salles’ analysis is stirring, astute, and ultimately delivered with a sigh: we always see the insurgent’s wind-up, a fiercely physical expression of possibility, the heroic moment of release. We rarely remember the retreat. And there is always a retreat, as the footage makes clear again and again, even in the moment. The stone is hurled, the momentum carries passionately outward, and then there are several steps back. We remember the general strike on the 13th, but not the hundreds of thousands marching for a reclaimed stasis on the 30th. It’s the film’s aesthetic and politics, embodied in the moment.

And then there is the famous image of the Parisian protester hurling a stone; you know the one. It adorns every depiction of the events of May, carried down to us by screenprints, Banksy, and, inevitably, the promotional materials for In The Intense Now itself. Salles’ analysis is stirring, astute, and ultimately delivered with a sigh: we always see the insurgent’s wind-up, a fiercely physical expression of possibility, the heroic moment of release. We rarely remember the retreat. And there is always a retreat, as the footage makes clear again and again, even in the moment. The stone is hurled, the momentum carries passionately outward, and then there are several steps back. We remember the general strike on the 13th, but not the hundreds of thousands marching for a reclaimed stasis on the 30th. It’s the film’s aesthetic and politics, embodied in the moment.

Still, Salles understands, or the poetry of his images understands, that we usually do not see what we see. Like a proper radical, he is prepared to be toppled by his own ideas, and In The Intense Now gives plenty of time to Cohn-Bendit, gleefully pointing out that May ’68 was never intended to last forever. It was a vast propaganda of the deed, an “orgasm of history,” in Yves Fremion’s phrase. When Sartre despaired at the students’ antipathy to platformism, the 23-year-old Cohn-Bendit all but shrugged at the great philosophe. Sure, there was an explosion; there were many explosions. “But there will be other explosions later on … The movement’s only chance is the disorder that lets men [sic] speak freely, and that can result in a form of self-organization”:

But now that speech has been suddenly freed in Paris, it is essential first of all that people should express themselves. They say confused, vague things and they are often uninteresting things too, for they have been said a hundred times before, but when they have finished, this allows them to ask, ‘So what?’ This is what matters, that the largest possible number of students say ‘So what?’ Only then can a programme and a structure be discussed. To ask us today, ‘What are you going to do about the examinations?’ is wish to drown the fish, to sabotage the movement and interrupt its dynamic. The examinations will take place and we shall make proposals, but give us time. First we must discuss, reflect, seek new formulae. We shall find them. But not today.

Sartre and Cohn-Bendit appear mythically here as the Marxist and the Anarchist, some sort of Aesopian fable we haven’t lived to see resolve yet into a moral. It pops up every time we are asked to give a 10-point plan, for it to be subsumed, in time or almost immediately, into the mechanics of governance or aesthetic despair.

Sartre and Cohn-Bendit appear mythically here as the Marxist and the Anarchist, some sort of Aesopian fable we haven’t lived to see resolve yet into a moral. It pops up every time we are asked to give a 10-point plan, for it to be subsumed, in time or almost immediately, into the mechanics of governance or aesthetic despair.

In many ways, May ’68 from Nanterre outwards was an aesthetic endeavor as much as a political one, as Salles well knows, its slogans “owing as much to the Surrealists as Marx.” Beauty is in the streets, sure; but also “Workers of the world, have fun.”

In The Intense Now is on the lookout for beauty, but fun is almost entirely elusive here. Salles’ found cinema often shows faces illuminated with desire, as ablaze as any burning barricade, but the joy vanishes as quickly as it emerges. The idea that it could be reclaimed, that there might be embers beneath the rubble, is outside the film’s many frames. It’s not just memory but an in memorium.