How do you approach making a bio-pic about a filmmaker like Jean-Luc Godard, whose aesthetic and political concerns are so deeply interwoven into the cinema of a particular time and place that entire strains of film history are unthinkable without him? How do you bend the hoary conventions of the mass-market bourgeois romance, the subversion of which was so central to his art, in illuminating ways?

It’s like writing a theology of Nietzsche, and the answer is almost certainly: You don’t. But if you accept the challenge of making cinema about a filmmaker who proclaimed its death, and then proceeded to interrogate its forms and warp his own mythologies for decades after the funeral over which he presided, you better think this thing through.

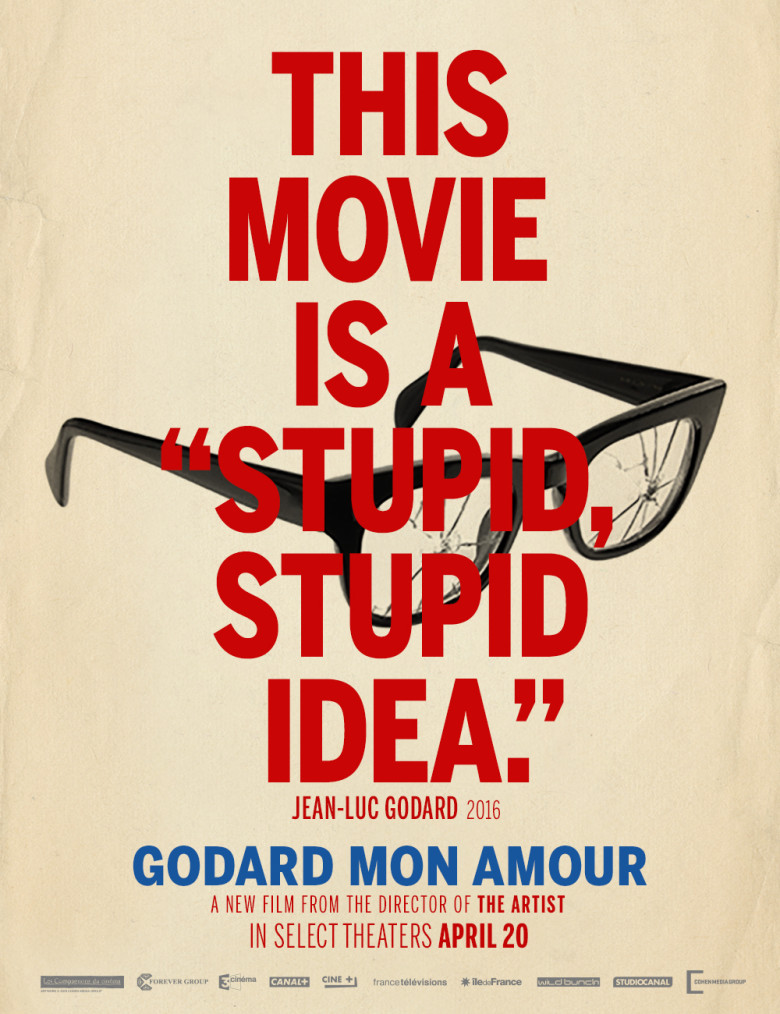

Thinking things through is not Michel Hazanavicius‘ strong suit. His Godard Mon Amour evinces virtually no understanding of its subject. It barely even registers an interest in an understanding. Like his Oscar-winning The Artist, a gimmicky “tribute” to silent film that also mimed an undergraduate disdain for an entire era he seemed mostly to have heard about second-hand, Godard is a checklist of references without substance, a hollow highlights reel that can’t distinguish saying something from meaning it. It’s the kind of film invariably described as “irreverent,” by which we mean “not funny, but generally shaped like a funny thing.” It is, as Godard himself pointed out when approached, “a stupid, stupid idea.”

Thinking things through is not Michel Hazanavicius‘ strong suit. His Godard Mon Amour evinces virtually no understanding of its subject. It barely even registers an interest in an understanding. Like his Oscar-winning The Artist, a gimmicky “tribute” to silent film that also mimed an undergraduate disdain for an entire era he seemed mostly to have heard about second-hand, Godard is a checklist of references without substance, a hollow highlights reel that can’t distinguish saying something from meaning it. It’s the kind of film invariably described as “irreverent,” by which we mean “not funny, but generally shaped like a funny thing.” It is, as Godard himself pointed out when approached, “a stupid, stupid idea.”

That this quote was used on a promotional poster is, of course, part and parcel of Hazanavicius’ irreverence. “See?” we are begged, “Godard doesn’t like it, curmudgeon that he is! Isn’t that fun? Well, isn’t it?”

Godard Mon Amour, adapted from the memoirs of actress Anne Wiazemsky, his second wife, positions itself from the get-go as operating at several removes. The couple’s relationship, spanning the tumultuous years of 1968 and ’69, overlapped with world historical events, on the streets and screens of Paris, and marks a pivotal point for Godard the filmmaker, essentially the frantic approach to what he considered an aesthetic and political dead-end.

There’s plenty here to examine, and, according to Richard Brody (the books haven’t been translated into English), Wiazemsky provides more than enough unsparing detail for a curious filmmaker to fashion something probing, empathetic, or vital. Not Hazanavicius. He “doesn’t so much adapt Wiazemsky’s memoirs as lay waste to them, pillaging the books for anecdotal sketches of a romance that he detaches from its surroundings, minimizing its intellectual fervor and historical urgency.”

Brody is too kind. Godard Mon Amour posits that Godard (Louis Garrel) participated in the Cannes boycott, in a leadership role no less, because of an offhand remark from a mocking student in the street, right before a pitched street battle takes hold, which Hazanavicius presents in montage backed by a jaunty Gallic score. Generally speaking, political commitment, when it surfaces, is a punchline, with a perpetually clueless Godard buffoonishly stumbling about, desperate for the kids to like him, up to and including an inability to stop talking politics even when he’s going down on his girlfriend. (A psychoanalytic analysis would ask where this film’s breathless desperation is actually issuing from.)

Brody is too kind. Godard Mon Amour posits that Godard (Louis Garrel) participated in the Cannes boycott, in a leadership role no less, because of an offhand remark from a mocking student in the street, right before a pitched street battle takes hold, which Hazanavicius presents in montage backed by a jaunty Gallic score. Generally speaking, political commitment, when it surfaces, is a punchline, with a perpetually clueless Godard buffoonishly stumbling about, desperate for the kids to like him, up to and including an inability to stop talking politics even when he’s going down on his girlfriend. (A psychoanalytic analysis would ask where this film’s breathless desperation is actually issuing from.)

As Anna, Stacy Martin is a flighty teenage know-nothing in thrall to a self-deluded, already past-his-prime oaf, the kind of girl who genuinely laughs when her lover demonstrates his unconventional approach to life by literally walking backwards when others walk forwards. There isn’t the slightest indication she’s ever had a thought in her pretty little head. The formation of The Dziga Vertov Group is played for laffs: Hazanavicius is one step removed from a bemused wag wondering how collectivists ever make decisions at meetings. This happy horseshit trolling continues unabated.

Garrel is encouraged to play Godard as the Forrest Gump of the revolution, stalking around with the mock-simian postures of a Groucho Marxist, minus the anarchist glee. A recurring slapstick motif finds Godard’s glasses repeatedly crushed, often by protestors, which does double duty in demonstrating that: a) he’s a Harold Lloyd figure, minus the athleticism, in perpetual danger of being pushed in a locker; and, b) that Hazanavicius discovered, in his research, that Godard wore glasses. At moments like this, we remember that we are watching an account of May ’68 from the guy who made the OSS 117 movies.

Garrel is encouraged to play Godard as the Forrest Gump of the revolution, stalking around with the mock-simian postures of a Groucho Marxist, minus the anarchist glee. A recurring slapstick motif finds Godard’s glasses repeatedly crushed, often by protestors, which does double duty in demonstrating that: a) he’s a Harold Lloyd figure, minus the athleticism, in perpetual danger of being pushed in a locker; and, b) that Hazanavicius discovered, in his research, that Godard wore glasses. At moments like this, we remember that we are watching an account of May ’68 from the guy who made the OSS 117 movies.

Apartments are festooned with copies of Mao’s Little Red Book and primary color installments (check). A long tracking shot (check) takes in the Situationist graffiti. Hazanavicius even has Garrel give the little speech about how he hates actors; later, this proud reference morphs into a nude Garrel and Martin declaring they’d never appear nude on camera. Interstitial pun titles abound, complete with overdetermined gunshot effects. There’s a dialogue in which the subtitles convey inner thoughts rather than the words spoken, a la Annie Hall, presumably because someone told Hazanavicius to look up signifier/signified on Wikipedia. Check, check, check.

Why, then, does Godard Mon Amour exist? For who? The biopic elements, that bourgeois romance, is clumsily intertwined, a transtexual Contempt for the Cliff’s Notes set. The whole air of insouciance, this trademark irreverence, advertises itself as a good-natured ribbing, but it is not. Hazanavicius seems determined to puncture a deflated balloon. Every moment has a sense of sticking it to the pretentious elites, the academic filmmakers and their slavish idolators, while simultaneously professing to have enjoyed the films once upon a foolish time.

Why, then, does Godard Mon Amour exist? For who? The biopic elements, that bourgeois romance, is clumsily intertwined, a transtexual Contempt for the Cliff’s Notes set. The whole air of insouciance, this trademark irreverence, advertises itself as a good-natured ribbing, but it is not. Hazanavicius seems determined to puncture a deflated balloon. Every moment has a sense of sticking it to the pretentious elites, the academic filmmakers and their slavish idolators, while simultaneously professing to have enjoyed the films once upon a foolish time.

In what world is that necessary? The festival crowd around me — these people who paid top dollar to be insulted by a guy who acknowledged he didn’t know much about the Hays Code, while making a film about it — laughed it up, knowingly applauding every half-studied reference, as impressed as parents of grade-school kids on report-card day. But, god, why? Art cinema is in need of being taken down a peg?

If The Artist was a tortured stand-up routine whose punchline amounted to, “Silent films? Those guys don’t even talk!”, Godard Mon Amour is simply beside itself. What a riot, the notion that anyone ever thought cinema could matter!

It’s too late for that joke, though. No one thinks that anyway.