Christine McPherson (Saoirse Ronan) — the preternaturally calm, quirkily rebellious titular protagonist who has renamed herself Lady Bird — seems awfully familiar. As the heart of Greta Gerwig’s adorkable coming-of-age-in-Sacramento writing/directing debut, her mannerisms, her slightly antiquated vernacular and social gestures, her entire mode of qualified suburban angst and dubiously offhand witticisms call to mind something or someone we seem to know. This is a strength and a weakness.

Lady Bird tracks moments in its lead’s final year of Catholic high school, the collection of soon-to-be memories of 2002, as she exits her parents’ nest and comes into her own. There are the requisite, awkward couplings with boys, shitty end-of-year dances with gauche adornments, the looming threat and promise of college. We’ve seen this story a million times, but it’s whimsically rendered and Ronan is ideal for the role, a world away from her soulful turn in 2015’s Brooklyn; here she embodies the inarticulately smart, affectionate, slightly daft generosity of … well, of Greta Gerwig.

Cue the familiarity. A more generous reading would argue that this sense of déjà vu is personal resonance – that everyone will find themselves, with a mix of embarrassment and a nostalgic grin, in Lady Bird’s characterizations. That’s surely part of it, and speaks to the film’s greatest strengths. (I was, I am sad to report, a total Kyle.)

But on a number of structural levels, this is a different sort of familiarity. It relates to Lady Bird’s status as something of an origin story for Frances Ha, replete with Joan Didion epigram. (In the age of the superhero blockbuster, even endearingly clumsy, millennial anti-heroism gets an origin story.)

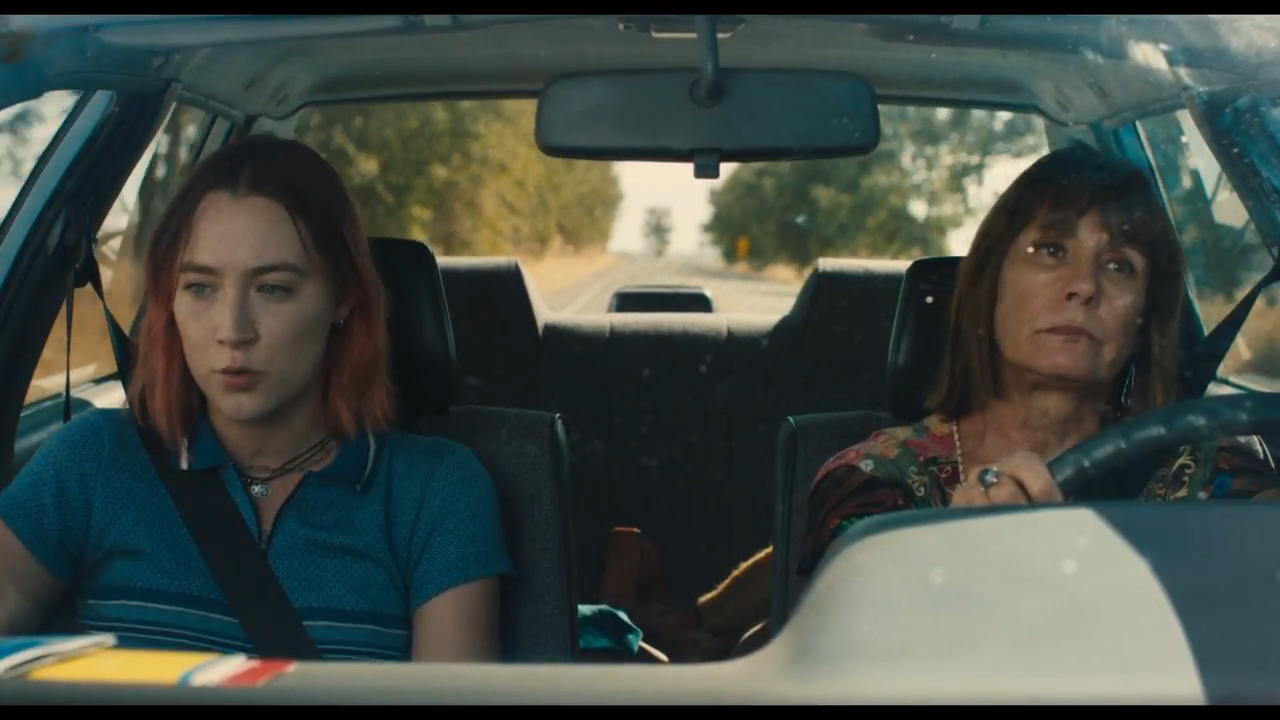

It emerges from the well-worn bildungsroman structure, an episodic treatment that calls to mind John Hughes with a Dave Matthews Band soundtrack. And it’s there, internally, in the generational doppelgangers: father Larry (Tracy Letts) and son Miguel (Jordan Rodrigues) vying for the same job in a fractured economy, mother Marion (Laurie Metcalf) and Lady Bird edited together in a lyrical, final reminiscence of gauzy, car-culture Sacramento, the “Midwest of California.”

All of this is, for the most part, played loose and snappy. There aren’t too many truly mumblecore moments, but the spirit of that movement, from which Gerwig emerged as its most familiar voice, remains. Lady Bird is fast and often funny, sprinting, like its hero, from scene to scene at a breakneck pace, eager to get out of Sacramento and on with life. Individual moments ring true – especially anything involving best friend Julie (Beanie Feldstein), the secret hero of the film – even if they seem to evaporate seconds later in the rush to get nowhere in particular. And, on that level, perhaps Gerwig has fashioned an acutely accurate portrait of adolescent longing.

Of some adolescences, anyway. For a film that self-consciously centers gender and class, Lady Bird is awfully quiet about race. The only non-white characters who play any real role – or, by and large, even show up on screen for that matter – are adopted brother Miguel and his girlfriend Shelly (Marielle Scott), both of whom Gerwig’s narrative sidelines with an almost comical shrug. (One conversational aside posits that they’ve become the same person since they started dating, which would be of a piece with both the focus on doubles and the amount of individual attention they receive from a story that thought they should be included but promptly forgot why, exactly.)

Of course, this forgetting is probably preferable to their cinematic cousin Long Duk Dong, who we remember all too well. Speaking of which, the outsized critical celebration of class-consciousness in Lady Bird is puzzling – one reviewer actually asks how many of these films even dare to address such things, as though John Bender and Claire Standish never existed, not to mention the entirety of Pretty In Pink. (Lady Bird, with its sartorial choices and even an explicit sequence in which a second-hand dress is altered at home, seems more aware of this anxiety of influence than its viewers, somehow.)

Still, Gerwig does ground Lady Bird in the economic anxieties of the time and place in a very non-Hughesian fashion. Marion’s entire character seems rooted in working-class privation, and it grants an almost believable edge to her unrelenting, borderline-manic pessimism about literally everything in her daughter’s life. Metcalf sells this beyond the script she’s provided – her reaction shot when her daughter’s date laughs that the family really does live on “the wrong side of the tracks” is heartbreaking – but you can feel the effort at every turn.

That groaning half-realism hamstrings the film’s central relationship – only in Lady Bird would its teen protagonist accept the mountain of emotional abuse heaped on her. This, we are told, is actually a brave reflection of female relationships, but it ends up lacking the honesty of Lady Bird’s friendships, relationships, and social group foibles, which benefit from Gerwig’s episodic approach. School does feel fleeting in the rush to adulthood; family doesn’t.

All of which might sound more negative than intended. Many of its faults – like “characters mov[ing] in the wrong direction on screen, so that meaningless little transitional scenes suddenly feel like a horror movie,” in Walter Chaw’s hilarious observation – reflect its first-film status. Others seem ingrained in the worldview presented, though not in any particularly awful fashion.

At its best, Lady Bird pulses with vitality, drawn from the strength its performances, its sympathy for the characters, and its unabashed affection, visual and otherwise, for Sacramento, or at least some sort of Sacramento-of-the-mind. Gerwig’s fans will warm to it immediately and her detractors likely roll their eyes a bit, for exactly the same reasons.

Which is fine. In an age of tentpole blockbusters and grueling reminders of the patriarchy at every turn, Lady Bird is still a welcome corrective — small-scale, female-centric, and guided by a personal vision.