I distinctly remember being in ninth grade, trying to convince friends to make a movie with me. The pitch: the opening scene of the film was interrupted by the lead actor being hit by a car; as the serious narrative went on, the film kept being interrupted by worse and worse accidents, by more and more actors leaving, until the last scenes were filmed by the director alone in his bathroom, depicting the action with dolls.

What I remember was giving this pitch to a friend. He turned to me and said, very seriously: “A movie about making movies?” A pause. “It’s been done.”

Somehow, the sheltered private school kids in my ninth grade class already knew that movies about making movies are as masturbatory as it gets. Pere Portabella’s 1971 Cuadecuc, vampir isn’t quite the typical entry, though.

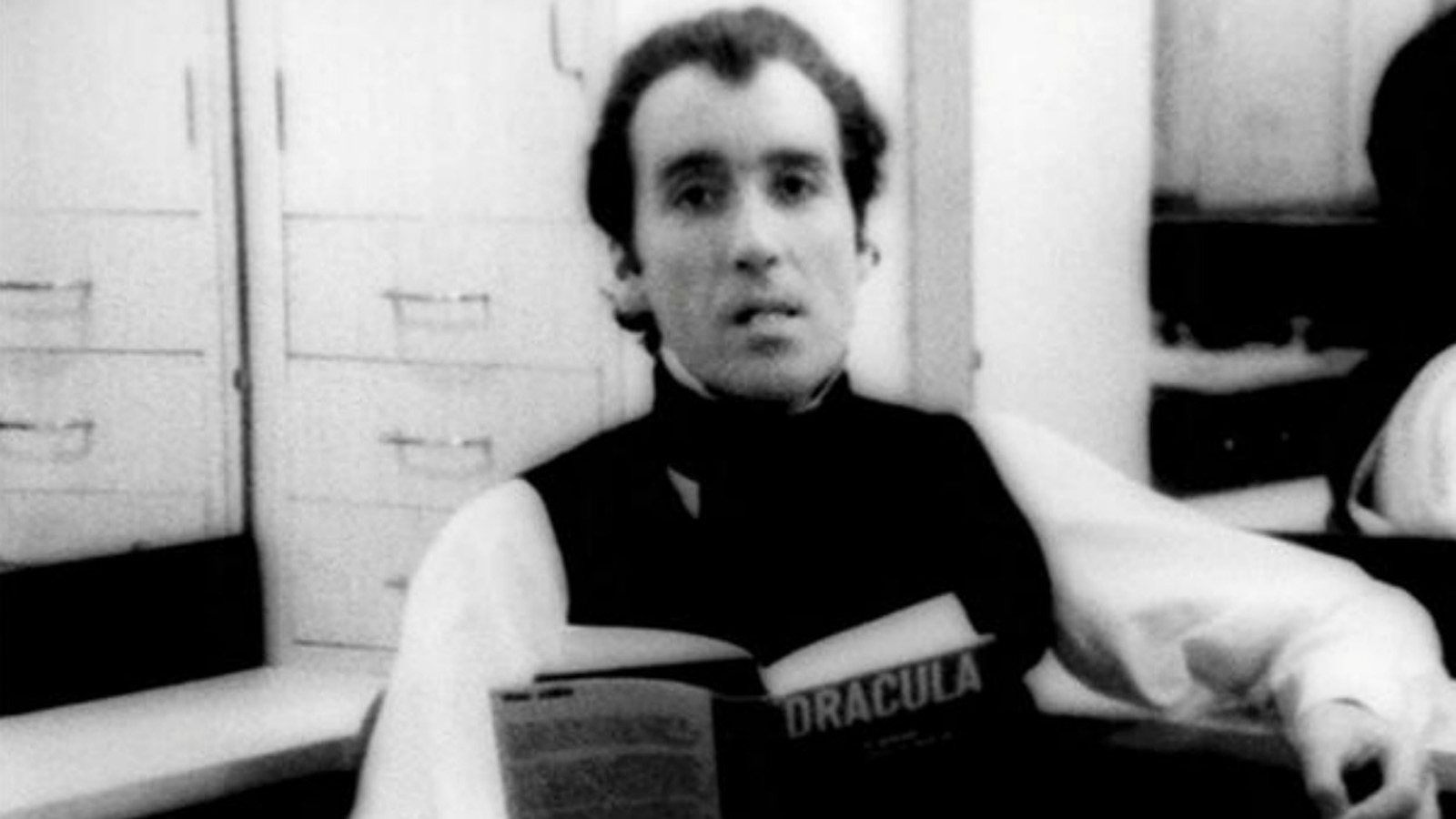

Cuadecuc is made up of footage shot on the set of Jess Franco’s 1971 Count Dracula, but, shot on very high-contrast black-and-white film with no spoken dialogue recorded, it can’t be called a documentary. Approximately two-thirds of the footage is shot as if it was diagetic, and we more or less follow the narrative of Franco’s Dracula film.

Cuadecuc is made up of footage shot on the set of Jess Franco’s 1971 Count Dracula, but, shot on very high-contrast black-and-white film with no spoken dialogue recorded, it can’t be called a documentary. Approximately two-thirds of the footage is shot as if it was diagetic, and we more or less follow the narrative of Franco’s Dracula film.

Between scenes, we see glimpses of set work: Christopher Lee, playing Dracula (despite this not being a Hammer production), lies in his coffin while PAs spray spiderwebs over him with a rotating fan; Maria Rohm and Soledad Miranda (as Mina and Lucy, respectively) ironically pose for Portabella’s camera.

But at no point do the interstitial scenes feel more real than the narrative ones. The complete absence of on-set sound (until the final moments) finishes what the cinematography begins, unmooring us as viewer from “the set” as a specific place. Instead, we are left with Carles Santos’ soundtrack, who sets everything to barely-audible drones and bleeps that sound like Stars of the Lid accidentally doubled their daily dose of laudanum.

The editing and camerawork, too, play too much into the story to allow the real and fictional worlds to settle into layers. Portabella uses a cut to turn Lee into a bat, matching Franco’s original cut, and the zooming handheld camera — Portabella regularly repeats that most characteristic of classic horror camera moves, the slow zoom on a woman’s horrified face — to invest emotional energy here and there, where it makes dramatic sense.

The editing and camerawork, too, play too much into the story to allow the real and fictional worlds to settle into layers. Portabella uses a cut to turn Lee into a bat, matching Franco’s original cut, and the zooming handheld camera — Portabella regularly repeats that most characteristic of classic horror camera moves, the slow zoom on a woman’s horrified face — to invest emotional energy here and there, where it makes dramatic sense.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, a vocal fan of Cuadecuc, sees in it a deep political significance. I will leave such speculations to those more informed about Portabella, who certainly was politically engaged in Spanish life, although I’m not sure the connection between Jess Franco the director and Francisco Franco the dictator is enough to go on. Even absent all subtext, though, Portabella’s film is a strange, wonderful thing, and deserves to be seen.