Part of an ongoing effort to watch a set of films from non-White, non-U.S., non-male, and/or non-straight filmmakers and depart a little from the Western canon. The intro and full list can be found here.

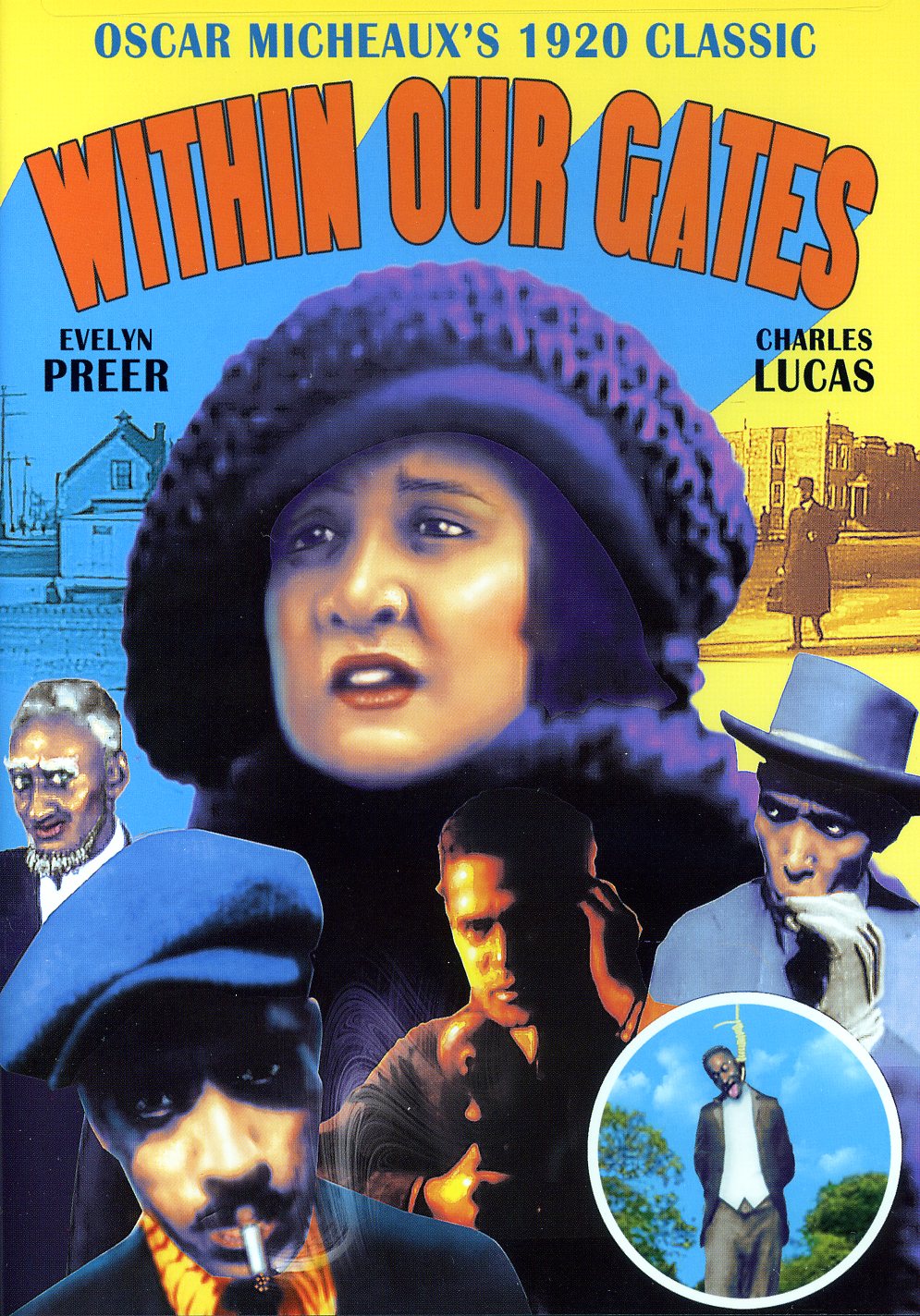

What if The Birth of a Nation, D W Griffith’s groundbreaking and deeply nasty epic, had been made by Black people in the U.S., the community it most excluded, caricatured, and vilified? Oscar Micheaux’s moving 1920 silent Within Our Gates suggests one answer.

Micheaux himself claimed his second film was not in direct response to Griffith’s notorious requiem for “the empire of the South,” but the mirror-image nature of Birth of a Nation’s plot structure and use of technical devices make that more than a little difficult to believe. Even taking Micheaux at his word and leaving aside questions of intention and influence, the similarities are fascinating and hard to miss.

While Birth of a Nation begins with white family members from the North visiting relatives on a plantation in the South, Micheaux’s film introduces us in its early scenes to Sylvia Landry, a Black Southern school teacher visiting her cousin Alma in the North. Sylvia’s waiting for her beau Conrad to return, in the hopes they will be married. Micheaux paints a lived-in, believable portrait of bourgeois Northern Black life – barely a white person to be seen until the movie’s half over – and lays the groundwork for a classic melodrama.

Alma, we learn, also loves Conrad, and so she engineers a situation in which Sylvia looks compromised, off alone in a room with another man (and a white one, at that). After a rage-fueled, but not lethal, attack on his beloved, Conrad flees, and we never hear from him again. (Apparently, he goes to Brazil, but this footage has been lost.) Uninterested in other local options, like Alma’s brother-in-law Larry, a petty thief and gambler, Sylvia returns home, to the South and to her school.

The school, Piney Woods, is facing tough times. Devoted to the education of Black children in the South, it is underfunded and overcrowded. Rev. Jacobs, who runs it, can’t bring himself to refuse any children who want to come, since he believes it’s both a Christian mission to accept them and a secular responsibility to future generations. This resonates throughout: the film frequently echoes W.E.B. Dubois in its call for education as a means of empowerment and self-determination, but also shows all the roadblocks – financial, ideological, and prejudicial – thrown in the way. While Jacobs and Sylvia believe an educated populace will be better positioned to fulfill their potential and less likely to be duped and abused, the wider society – mostly Whites, but some Blacks too – actively wants to maintain the status quo.

On the brink of bankruptcy, Sylvia again travels north, this time trying to raise the needed funds to keep the school open. She has little luck, until a White woman hits her with her car one day. (An extreme but effective source of school funding.) It’s an accident – Sylvia had pushed a child out of the car’s way – but the vehicle’s owner turns out to be a wealthy, forward-thinking philanthropist, and hearing Sylvia’s pitch, agrees to fork over the money. Their interaction has a bit of the flavor of Birth of a Nation’s Ben Cameron in the hospital after being wounded sheltering a Northern soldier: in both cases, their selflessness and willingness to put their bodies on the line for those on the other side of the ranks are rewarded.

The sequence in which Sylvia explains her predicament is the first time, of several, that Micheaux deploys a flashback. For all its lauded cutting between locations, Birth of a Nation was never so audacious. As she describes the school, we get a soft dissolve to earlier footage of a father dropping off his kids to Rev. Jacobs, entrusting him with their future, and then back to Sylvia. It’s a technique we take for granted now, but the first time I’ve seen it in any of the films on the Great Movies list.

Of course, this is the same year that The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was messing with perspective and time and a full five years since Birth of a Nation came out, but it’s notable all the same. The audience is meant to understand that events depicted on screen are not happening in sequential time, that memories are being invoked for current action. And we do, instantly.

Even more elaborate flashbacks are in store. After securing the school’s funding, over the objections of a deeply racist acquaintance of the benefactor, Sylvia’s story comes to light. The film effectively leaps backwards in time, and then circles around to show how her history impacts the story in the present. While Within Our Gates is aesthetically pretty staid, content with mid-shots for the most part, its narrative structure is daring.

Our leap back to Sylvia’s past reveals that her own education, and her ability to recognize her adoptive parents were being ripped off by the landlord, leads to the lynching of her entire family. We understand that her passion for education is rooted in this. Unlike Birth of a Nation, Within Our Gates shows the horror of lynching in full, in this case cross-cut with an attack on Sylvia by a white man (who ends up being much closer to her than either of them realize).

Where Griffith’s film was fixated on the ever-present threat of Black male sexuality (representing the dangers of a new social order), Micheaux focuses on the much more proximate (and real) horror of white terror. It’s a terrifying vision, and the film argues there are few ways out.

There are several lynchings in the film, and even more references to them. This is a world apart from Griffith’s bucolic South, and offers a welcome corrective.

Micheaux also levels his sights at the palliatives of religion – embodied in the figure of Old Ned, a hypocritical pastor who tells the congregation to keep their heads low and wait for heaven – and Efrem, a shucking and jiving kissass who mainly wants to curry favor with the whites in power. It doesn’t end well for either of them, despite their allegiances.

However, even Old Ned and Efrem are extended sympathy from the film. There’s the sense that individuals are doing what they feel they need to get by, and that the social order itself is sick.

Like many a story before it, Within Our Gates closes with a marriage. It signals hope for a better day, and the title cards urge Black folks to acknowledge their centrality to the nation and resist notions of Otherness – “We were never immigrants,” one character says.

The film, as it exists today, is in many ways a bit artless, but that’s an incredibly radical sentiment for 1920, accidentally evoking Malcolm X’s famous statement, “We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock. The rock landed on us.”

Within Our Gates is generally grouped with what were known as “race movies” – that is, movies that featured largely Black casts and dealt with these issues in the teens and 20’s. But it’s also a fascinating interrogation of contemporary norms and a challenge, to Griffith specifically (no matter what its creator says). It’s generally considered the oldest film from a Black director that has survived.

Even in 1920, filmmakers like Micheaux were trying to capture the nuances of everyday lives that we don’t usually see on screen. Whether he did it to open the field up for different representations, as a response to mainstream depictions, or just because these stories spoke to him, it can’t help but stand in contrast to the larger, whiter paradigm that dominated then, and continues to dominate now.

Watching Within Our Gates now, I’m most struck by how much is packed into this thing: an anti-racist narrative, anxieties about mixed race heritage, women’s suffrage and white Northern women’s racist opposition to it, the Great Migration, long discourses on education and the desire of parents everywhere that their kids will do better than they did. It’s amazing how many themes Micheaux hits which still resonate.

Mostly, I’m struck by the blending of its characters’ longing for a better world, and the brutality of the one in which they find themselves. Some things don’t change.

Next up: Body And Soul, another from Micheaux, starring Paul Robeson.