It’s only May, but the top contender for documentary of the year has already arrived. Jason Zeldes’ portrait of Richmond, CA and the struggles of its youth in an incredibly dangerous environment is a staggeringly emotional and moving film. It provides narrative context for its subjects, and is both visually interesting and accomplished, but it also has the good sense to let these kids speak for themselves. Holy shit, do they ever.

The film portrays a city under siege, where those from the north and central parts are locked in intractable violence, dating back decades. Or more: the unincorporated part of the north side was where Blacks who came westward to work in the shipyards were pushed a generation ago, a division literally demarcated by train tracks. The Chevron refinery, prone to blowing up every few years (including during the production of Romeo Is Bleeding), spews toxins into the community. Draconian gang injunctions – arguably borne out of a desperate attempt to still the gun violence – essentially criminalize the vast majority of the population. It’s the kind of place where almost no one at all is untouched by the ongoing strife and agonizing list of fatalities.

And in the midst of all this, kids write poetry, trying to get a hold on what they’re experiencing.

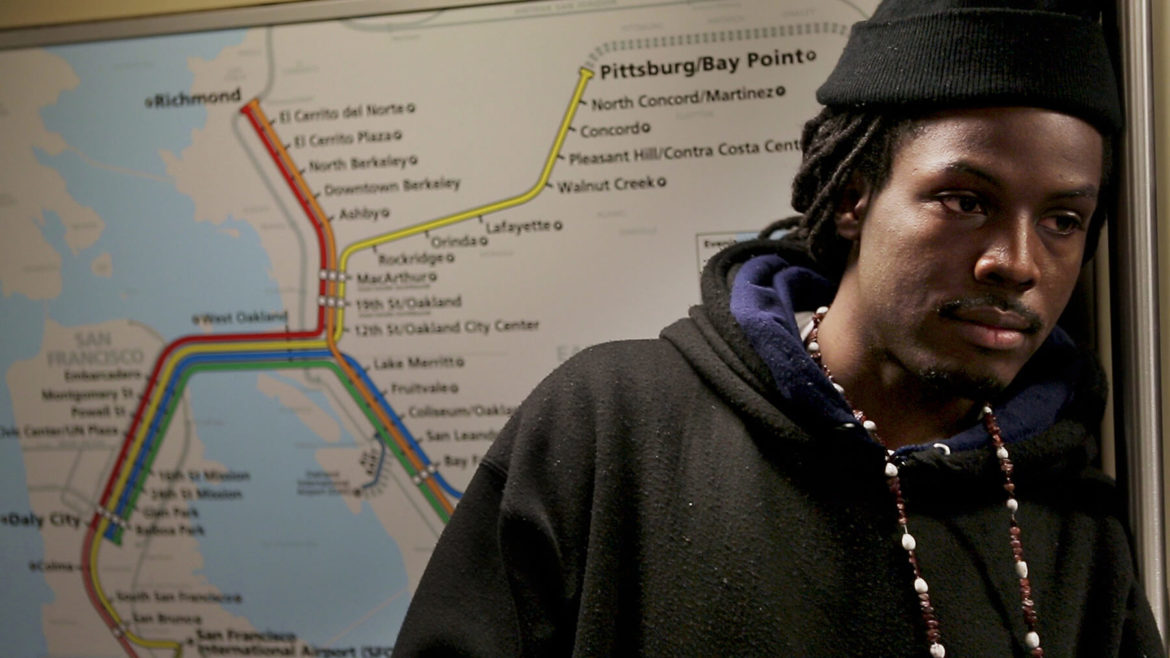

The film focuses on Donté Clark, an older but still young poet, and Molly Raynor, who together set up a spoken word and mentorship program for the youth of Richmond. Clark’s a lifelong resident, with family ties to a pivotal incident that might’ve played a huge role in opening the chasm between North and Central, which has been steadily filling with murdered Black men ever since. Without putting too fine a point on it, it’s clear this weighs on him. To the film’s credit, though, he’s not a salvational figure, and neither is Molly. They’re both driven primarily to give voice to the kids – or rather, allow the kids’ voices to come into their own, convinced that the silencing itself is a precondition for the violence.

After remarking on how the balcony of a particular theater they find themselves in would make for a good Romeo and Juliet, Molly proposes they stage one. Donté laughs it off – what do Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers have to do with Richmond. “Nobody would come to that play,” he laughs, not without reason. Then a bit later, he remembers how he read it again, no longer a disaffected 15 year old but as a 22-year-old poet and thought: “Oh shit, this is my life.” It is, after all, the story of violence between crews, of turf wars, of kids who’ve inherited the world their fathers fucked up and so find themselves acting out vendettas they don’t even really understand any more.

The decision? Donté and the group of young poets rewrite the play, holding on to plot beats and some of the language, while transposing it to Richmond and infusing it with rapid-fire spoken word and hip-hop rhythms. The poets draw on their own experiences to talk about home, family, doubt, grief, and rage. And they debut it in El Cerrito, for a crowd of their peers.

If you’re not sort of tearing up at the prospect, I worry about you.

In between footage of rehearsals, we get unobtrusive back stories and snippets of others – neighbors, family, even cops – talking about how things play out in Richmond. We get the frantic evacuation of their practice space downwind from the Chevron explosion, something the film makers couldn’t have anticipated but which just underlines the environmental racism of the situation.

And things being what they are, we bear witness to yet more tragic loss. It’s a lot to take, and the film doesn’t take it lightly, but it also keeps bringing things back to the topic at hand – the neighborhoods aren’t going to be fixed over night, but these kids have things to say and a forum in which to say them. This is valuable, they desperately want it, and self-expression has to start somewhere. To its profound credit, the film takes them totally seriously as both artists and goofy children all too aware of the dangers they face.

There are many ways this could’ve gone off the rails. It could’ve been maudlin, or disrespectful, or “important” (that “eat your vegetables” variety of damning with faint praise) or so worshipful that it obscured the flawed humanity and anxious doubt coursing through the whole thing. It is none of those things. It’s an honest, beautiful, and ultimately profound mediation on art and life, located in a particular place and time, and filled with individuals you immediately want to know better. It was screened at the San Francisco International Film Fest, where it received standing ovations at each of its three showings.

There may be a better documentary this year, but there won’t be a more vital one. It should be screened in every high school in the country. Or, as Raynor suggested in the Q&A, paired with Shakespeare’s play in the curricula. With the near-annual laments about declining readership for The Bard, maybe that’s something everyone can get behind. The connections these poets make to the source material are deep and wonderful, and the stories they tell need to be heard far outside the borders of Richmond, California.