“In the event that find certain sequences or ideas disturbing, please bear in mind that this is your fault, not ours. You will need to see the picture again and again, until you understand everything.”

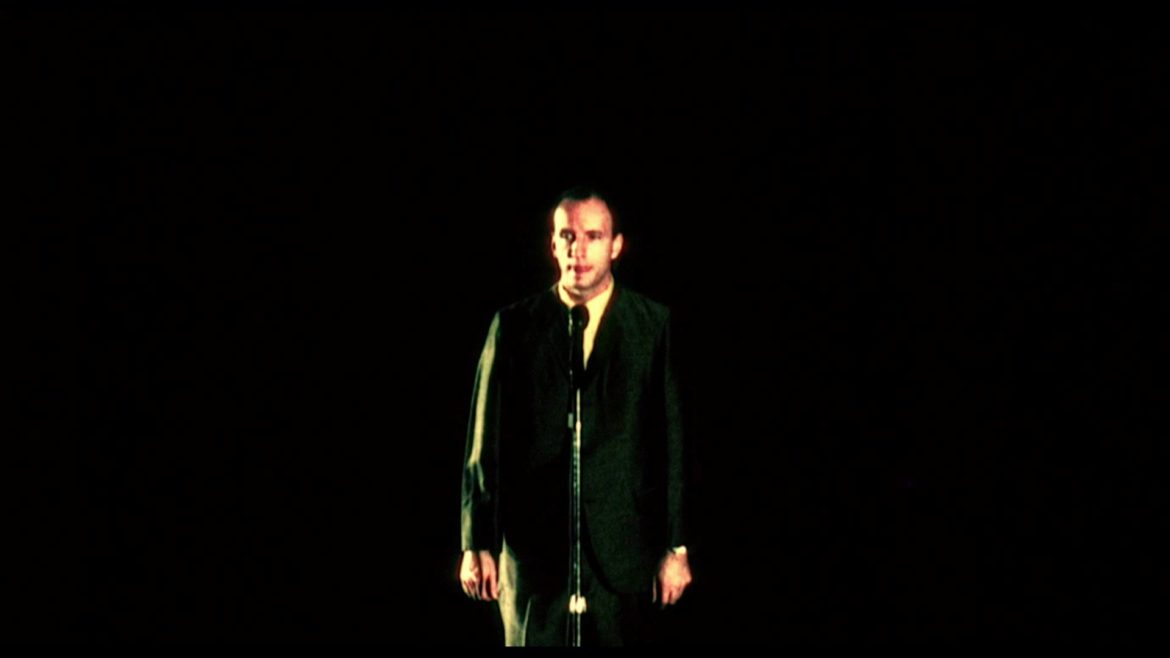

This delightfully caustic warning, uttered by director/star Steven Soderbergh in the first moments of the film, sets the tone for Schizopolis. Entering and exiting the stage half-bowed, like a carnival barker or a cut-rate Hitchcock directing from the proscenium (my new favorite word), he adds that you should pay full-price.

It’s a bitter, angry joke, but it’s still pretty hilarious. There are a lot of those in Schizopolis. The surprise is how melancholy things get. This is a film with no intro or ending credits, that spins wildly between comic plots in its typically Soderberghian three-act structure, and one which begins and ends with a pantsless man on a bicycle. Yet, beneath the breathless antics and absurdist shenanigans, it still manages to suggest a deep weariness.

Soderbergh plays both Fletcher Munson, an office grunt with higher ambitions, in the employ of one Theodore Azimuth Schwitters, an L. Ron Hubbard-like bullshit artist and founder of “Eventualism” (sample dogma: “Eventualism is not a cause, a course, a fashion, or a religion. Eventualism is a state of mind.”).

He also plays Dr. Jeffrey Korchek, a vainglorious, frequently jogging suit-clad dentist having an affair with Munson’s wife, who gets in over his head thanks to his own proclivity for writing notes to his female patients. These notes veer wildly between unfortunately misguided lyricism and, let’s say, inappropriate honesty. “Attractive Woman #2”, as she’s known, receives this sentiment in the mail, surely what every woman wants from her dentist:

I may not know much, but I know that the wind sings your name endlessly, although with a slight lisp that makes it difficult to understand if I’m standing near an air conditioner … I know that if for an instant I could have you lie next to me, or on top of me, or sit on me, or stand over me and shake, then I would be the happiest man in my pants.

Unsurprisingly, this bold gesture has professional consequences, along with personal ones. It’s a rough day. And that’s not even taking into account the unsavory type out to get to him thanks to his addict brother, and the subsequent theft of all of his money.

Laying out the plot further is a fool’s errand, mainly because Schizopolis is as much an interrogation of plot devices as it is an actual movie in the traditional sense.

For instance, one of its key figures, an exterminator named Elmo Oxygen who speaks in a carefully orchestrated nonsense language, is introduced in the first act only to renounce his participation in the film in the second, leaving to start his own reality show, and return to play a key role in the third. Before things fall apart, Soderbergh’s Korchek gleefully notes that he’s having an affair with his own wife (which is to say, Soderbergh’s Munson’s wife). At its conclusion, Munson flash-forwards to let us know how things turn out for him: with mock pathos, he tells that, in eight years, he will be drunkenly fall asleep in the snow at a wedding in Alaska and be discovered months later … and successfully thawed. When director Soderbergh (as opposed to Korchek or Munson) returns to take questions from the audience, we hear his answers but not the questions from the imaginary audience: “Yes. Yes. Foot-long veggie on wheat. Yes. Thank you.” The entire movie is a Dadaist dive into the meta.

It’s also an acerbic examination of the use, and the mis-use, of language. The examples are too numerous to list – they essentially constitute the film. Elmo’s repeated use of “nose army” and assorted lunatic vernacular. The confusion between Korchek and the strongman trying to extort him, as they repeat the sentence “Your brother, eight hours, fifteen thousand dollars” to each other, growing increasingly puzzled. Banal conversation is exchanged in descriptions of its contents, like this portrait of a sexless marriage:

– Ooh, really well-rehearsed speech about workload and stress.

– Genuine sorrow.

– Um, truthful-sounding promises of future satisfaction? Enticement to agree?

– Accepted.

– Gratitude.

Entire scenes are played with one character overdubbed in different languages, and then are replayed later with yet other languages substituted. There’s frenetic action everywhere you look in Schizopolis, and constant wordplay, but no one can understand each other.

This gets to the heart of the very funny movie’s sad center. In an invaluable conversation about Schizopolis on The Solute, two of its contributors point out that Munson’s wife (and Attractive Woman #2) is played, excellently, by Betsy Brantley, Soderbergh’s ex-wife. Without that knowledge, one gets the sense that deep personal pain informs this madcap piece of cinema; knowing that, it’s impossible to ignore. It also came at a time of professional frustration for Soderbergh, and, in consistently inventive ways, showcases a talented director both taking aim at the industry and exorcising his own demons.

The film is at once hilariously irreverent and deeply mournful. It’s a gonzo masterpiece and I’ve never seen anything like it.