The horrifying saga continues. October will not be denied.

Taking stock, here is where we find ourselves on October 18th: 7 films from franchises, done; 5 decades, done; 5 films from before 1970, done; 1 silent, done; 1 classic Universal horror, done; 1 film with a witch/witchcraft, done; 1 Tobe Hooper film, done.

This leaves several criteria to hit for the rest of the month.

Before the end of October, we still need six countries (this is arguably satisfied, but Possession is technically a French/German co-production and so I’m not sure how to count it). I have first-watched nothing from Bava, Argento, Lenzi, Fulci, Henenlotter, Romero, or Stuart Gordon, much less five separate films. The quite poor Lake Placid, discussed below, is only the first of the requisite three crazy animal movies, and not particularly crazy at all, but let’s leave that to the side. The 2011 Fright Night needs its 1985 predecessor. And Stephen King has yet to make an appearance.

The clock is ticking, ominously.

Will I make it out alive? Will I satisfy the arbitrary requirements of this self-imposed challenge? When October ends, will I expect every movie, from quiet relationship dramas to slapstick comedy, to feature incongruous jump-scares and/or crocodiles?

Only time will tell. (By which I mean, “yes, probably”.)

The Fall of the House of Usher (France, 1928, before 1970, silent)

The most recent entry in the Great Movies series does double duty here. Liberally combining elements of multiple stories from Edgar Allan Poe, the great French director Jean Epstein conjured something fantastical and creepy. Serving both as a singularly cinematic treatment of the macabre and coda to a particular moment in the avant-garde, Epstein’s Usher is awash in dreamscape impressionism. Despite Ebert’s insistence, like many others’, that it is a work of Surrealism, Epstein is up to something else — a totalizing vision where every aspect in the frame correlates to psychology and message. Despite the participation of co-writer Luis Buñuel, that’s effectively the opposite of Surrealism, as would become clear with the two filmmakers’ mutual rejection and antipathy, underlined by the release of Un Chien Andalou the following year.

Movement credentials aside, though, Epstein’s quasi-Romantic, post-Freudian vision of obsession, hauntings, control, and the repressed is entirely effective as ghost story and silent film. He pulls out all the stops, and arrives at a film state somewhere between sleep and waking. Call it Lynchian, if you like. Regardless, it’s an unnerving masterpiece.

Friday The 13th: The Final Chapter (franchise, U.S., 1984)

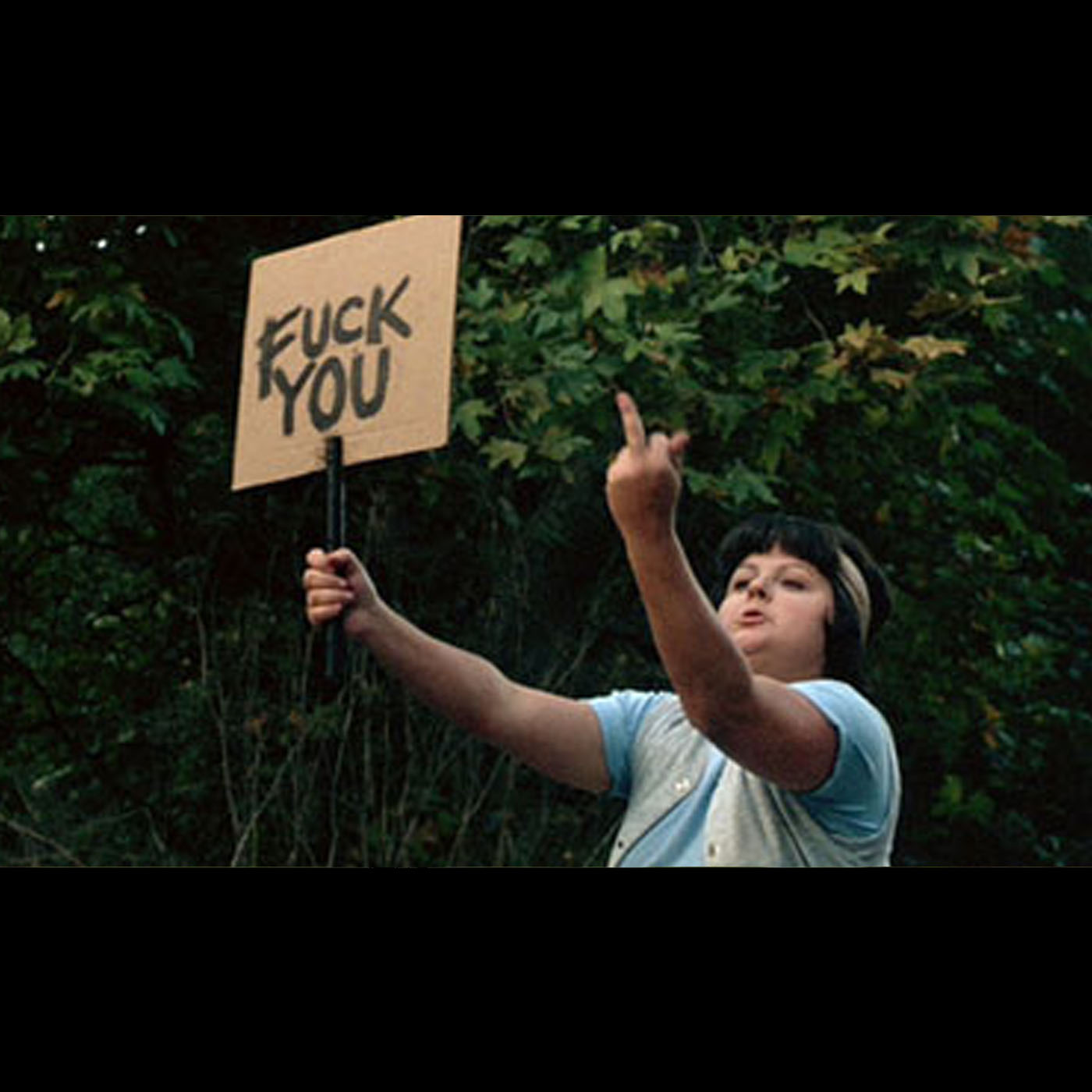

This still, featuring a minor character, sums up my reaction to Friday The 13th: The Final Chapter.

First of all, as we know, it is not the “final chapter”. Secondly, it is not scary when Jason throws people out windows. The presence of a young Corey Feldman and an eternally teenaged Crispin Glover, delivering his line “I’m soooo horny” in hilarious fashion, help mitigate the death march to nowhere. But this is just paint-by-numbers-in-blood schlock.

At least we’ll always have this.

Fright Night (U.S., 2011, an original and its remake)

As noted, I’ve yet to see the original Fright Night, and so I have arrived at this 2011 remake in questionable order.

That said, the 2011 Fright Night is a ton of fun. The performances — from Colin Farrell, David Tennant, and the late Anton Yelchin — are all perfectly suited to the self-aware hijinks of Marti Noxon’s post-Buffy script. There’s tension, gore, and comedy (in that order). No one is going to hail this film as groundbreaking — the film itself would mock them for doing so — but it scratches a particular itch.

The whole central conceit of the Vampire Next Door is perfectly in Noxon’s wheelhouse, equally mining high school anxieties and middle-aged divorcee desire for that patented, blood-soaked wit. Plus, without Joss Whedon there to muck it up with relentless punning, Fright Night is just straight-ahead drive-in fare. Tennant, especially, seems to be having the time of his life, as a part-charlatan vampire expert, swaggering about and quipping.

Lake Placid (U.S., 1999, crazy animal)

What do you get when you cast Bridget Fonda, Bill Pullman, Brendan Gleeson, Oliver Platt, and Betty White in a film about crocodiles, written by TV scribe David E. Kelley?

Not a lot! Lake Placid asks us to suspend a lot of disbelief — in the way things work, in how people talk, in the responsibilities of both Fish & Game Wardens and New York City museum paleontologists, in the idea that Oliver Platt is charming. In fact, it asks far too much, and delivers far too little.

There might be a good crocodile monster movie gestating in someone’s fevered imagination right now. It is not this one, which relies on post-Jurassic Park CGI of the most half-hearted variety, the woodsy sexual allure of Bill Pullman, and Betty White saying “hilarious” things like, “If I had a dick, I’d tell you to suck it right now.” Stop that, Betty White. Stop it, all of you.

The Old Dark House (U.S., 1932, before 1970, classic Universal)

This is no Bride of Frankenstein, but James Whale’s creaky, creepy The Old Dark House does feature Boris Karloff in a mostly mute turn, alongside an ably talkative cast and a whole lot of shadows.

The standard genre tropes are all dutifully deployed, familiar to any acolyte of October scares: weary travelers in a storm, a mishmash of characters sequestered in close confines, weird noises from upstairs. They’re then combined with stage-y comic bits. Charles Laughton is there to declaim and speechify, but most of the fun comes from the rapid-fire interactions and the final, fiery set-piece, complete with burning banisters and hands, emerging from the darkness, to surprise the terrified guests.

The Omen III: The Final Conflict (franchise, U.S., 1981)

The eeriest aspect of the original Omen — apart from Jerry Goldsmith’s iconic score and its famous “It’s all for you, Damien!” scene — was its ending. The film presented a vision of corrupted innocence and a sense of the inevitable dominion of Evil that helped round out its more ridiculous moments.

Oddly, The Omen III: The Final Conflict presents a world in which Damien’s triumph is not so assured at all. An entire theology informs its machinations — there are 7 sacred knives to kill the Antichrist, there’s a cabal of the holy and a counterforce of Satanic minions, and so forth. We are no longer held in dread about Evil’s triumph; as the title suggests, we only await the battle.

Still, Sam Neill (appearing for a second time on my October list, after his memorable turn in Possession) is an ideal adult Damien, that son of the Devil devoted to Hell on Earth. Neill runs a multinational food and commodity conglomerate (because of course he does), while also angling for an Ambassadorship to position himself for his Father’s return. In the meantime, he carries on wildly in monologues with blasphemous statues of Jesus, and gets caught up in a plot to murder the infant Christ, whose second coming has been foretold and has now come to pass.

The Omen III is often ridiculous itself, but compulsively watchable. Its final moments lapse into self-parody, but there is so much going on here — the elision of corporate interests and manifest evil, the convoluted Daddy Issues seeming to affect everybody on Earth and Beyond — I’m willing to give it a pass. If I slammed my beer down in frustration two minutes before the credits, it was out of affection for what preceded them. This is very close to a good horror movie. It’s certainly an interesting one.

What We Become (Denmark, 2016)

We covered this last week, when it showed up new to streaming on Netflix. It’s a taut and smart treatment of zombie mythology, but one much more interested in the ways we cope with trauma than the visceral, face-biting nature of the trauma itself. Until the end. Then, there go the faces.

The bloody climax is all well and good, though, and likely to please the October gore-fans who patiently waited. For everyone else, What We Become is a study in how quickly and resolutely the structures of bourgeois society can unravel. The idea that we ought to lock our doors, take care of our own, be reasonable, keep our heads down, trust in authority … these are monstrous conceits, in context.

Especially when that context involves actual monsters.