Happy Labor Day!

You know, the day in early September that Grover Cleveland declared a federal holiday as a halfhearted apology for his troops murdering several workers during the Pullman Strike in 1894, a desperate, election-year attempt to stave off radical reform while also conveniently distancing the U.S. from the rest of the world’s celebration of the far more militant May Day, with its overtones of worker solidarity and outright revolution!

Oh well, at least some people get the day off, anyway. Let’s talk about movies.

The notion of the “labor film” is fairly malleable. After all, work, however defined, constitutes much of our lives; you don’t have to be a Marxist theorist to notice how greatly a character’s job or need for income frequently drives narrative. We could call every heist movie a “labor film” if we were so inclined. If someone is either rich or poor or in between, that’s a “labor film”. Class-consciousness and the oppressive demands of workaday society — accepted, grappled with, rejected for alternative modes of being, ignored altogether in favor of escapism for audiences looking to forget about a bad day at work themselves … these are “labor films”. In a very real sense, there are only labor films.

But we approach tautology. Over the years, many films have focused specifically on work and class, often explicitly intertwined with race and family (and how could they not be?). Several have already been included in the Great Movies series and its Counter-Programming companion: The Battleship Potemkin, The Last Laugh, Safety Last!, Let’s Go With Pancho Villa!, God’s Step Children, Street Angel, The Goddess. It is an enduring theme that has animated the cinematic imagination since the beginning.

In that spirit, here are five more recent favorites. The contexts, locations, and politics may shift, but work itself is a constant. Until the revolution comes, here are some suggestions for your queue.

Long-banned and notoriously hard to view for years, Salt of the Earth (1954) is a truly radical film. Scripted and shot by blacklisted filmmakers, it’s the story of a general strike called for by exploited Mexican workers at a zinc mine in New Mexico. The attention to class struggle and immigrant status would be striking enough for 1954, but Salt of the Earth goes much further, zeroing in on gender conflict within the community of working people and laying bare the ways in which masculinity itself is defined by class under capitalism. It’s an incredible film that should be compulsory viewing for anyone interested in social change.

2) Matewan

John Sayles’ depiction of the bloody events of 1920 is another film preoccupied with intersectionality, skeptical strikers, and uneasy solidarity. Tracking a West Virginia coal miners’ strike encompassing white, Black, and foreign workers, Sayles delivers a cinematic love letter to the IWW’s “One Big Union” concept — the notion that, as Chris Cooper’s organizer protagonist proclaims, “There’s only two classes: them that work and them that don’t,” race be damned. “We work. They don’t.” A young Will Oldham, of Palace and Bonnie “Prince” Billy hipster-fame, steals the show as an aspiring preacher who finds in Scripture a call to solidarity and rejection of the bosses, declaring, as he leaves the pulpit to escape armed Pinkerton agents, “And if Jesus were alive today, he’d be a Union man.” His elder relative, almost silent the whole film, responds, “Praise Jesus” as he flees.

I love this fucking movie.

3) 9 to 5

A comedy so radical and forthright in its feminism and class-consciousness it features not one, not two, but three fantasies about killing your boss. I still can’t believe it was ever made, much less successful with audiences. It’s a gonzo, bananas narrative about workplace takeover, it’s attenuated to gender and class expectations, and it works on every level. The theme song has remained a classic, but many forget just how confrontational it is.

They shouldn’t; it’s right there in the damn song! “It’s a rich man’s world, no matter what they call it / And you spend your life putting money in his wallet.” You tell ’em, Dolly.

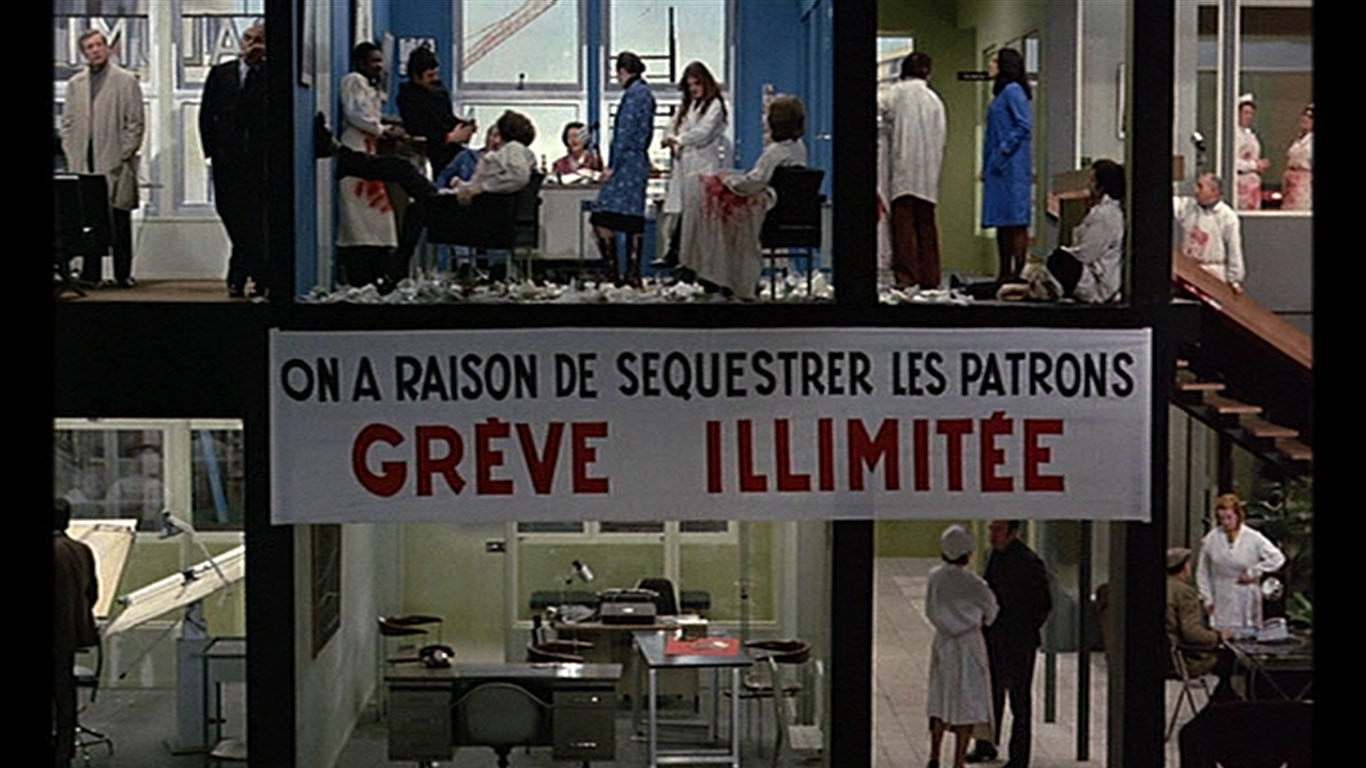

4) Tout va Bien

Godard’s feverish hate-letter to consumer capitalism, Tout va Bien is positioned exactly between the well-liked New Wave period and the much-derided Maoist productions of this auteur’s auteur. In some ways, it’s a synthesis of both sensibilities. A sausage factory strike sets the (rather literal) stage for Godard’s evisceration of systems out to dehumanize and deligitimize, while Jane Fonda and Yves Montand break fourth walls and generally lay waste to narrative expectations. Filmed like a stage-play gone mad, Tout va Bien is a post-’68 grenade hurled at the viewer, an irrepressible intervention in the cinema of discontent.

Agnes Varda’s self-reflexive portrait of people digging through the refuse to find and repurpose things mainstream society has discarded might not seem to fit the bill here, but I think it’s among the greatest labor films ever made. (Incidentally, the English translation of the French title — Les glaneurs et la glaneuse — isn’t just gramatically awkward; it actually obscures the centrality of her role and its meaning. Fucking Americans.)

Implicitly addressing consumerism and the ideologies that create “waste” in the first place, Varda approaches her subjects’ labor on the margins with wit, compassion, and nuance, while also drawing attention to the kinds of work we do as viewers and meaning-makers. Unlike Godard above, there’s no fist in the air. This is a melancholy reflection on outsider status and changing modes of living, but also a celebration of the ways in which humans refuse to knuckle under to oppressive control. It’s a beautiful and incredibly smart film, absorbed by possibilities and struck through with empathy.