One of the fascinating revelations gleaned from the Silent Era is the degree to which there really is nothing new under the sun. As Martin Scorsese told Roger Ebert, “Each film is interlocked with so many other films. You can’t get away. Whatever you do now that you think is new was already done in 1913.” Suspense, co-directed by Lois Weber and her then-husband Philips Smalley and not coincidentally appearing in that same year, is a case in point.

Suspense traffics in tropes that are immediately recognizable for modern audiences — an isolated potential victim, a menacing figure outside the home, possible help from a third character (in this case, the husband) who is some distance away, a clipped phone cable shutting down contact to the outside world.

Weber and Smalley might’ve called their film Suspense, but it just as easily could’ve been titled “Horror”, were that word not so associated with monsters and the macabre at the time. Weber herself is a fascinating figure, the leading female filmmaker in early Hollywood and, for a time, its highest paid. A dedicated suffragist who often deployed the camera for political purposes, making controversial, moralistic pictures about capital punishment, drug abuse, and contraception.

In Suspense, nothing is high-minded (though Charlie Keil argues that the film “shows us how the social- patriotic drive to celebrate women as icons of domesticity unravels”). Weber plays the female lead, a mother tending to an infant at home. Her servant walks off the job for reasons left mostly unexplained: her note simply indicates she can not work in “so lonesome a place,” an interesting touch of foreboding to the proceedings.

Meanwhile, her husband is off in the city at his office, and a menacing tramp is lurking about the grounds. Weber’s character, isolated in the empty home, is in danger. Her panicked phone call to the husband ends abruptly as the Tramp cuts the line; the husband, frantic, steals a car and races home to her rescue, even as he’s chased by the police and the car’s owner, who don’t understand the peril and urgency. This is all the stuff of horror movies, right down to the uncomprehending authority figures who are placed in a position, through their ignorance or disbelief or arrogance, of standing in rescue’s way.

Weber and Smalley introduce a number of technical innovations to this familiar tale. Bordwell recounts them. There are menacing close-ups as the Tramp climbs the stairs directly to the stationary camera, which watches his approach with mounting dread rather than following him laterally. There’s an incredible shot — “near-Hitchcockian” — that views the Tramp from above, taking the wife’s POV from an upstairs window as he looks up.

Another shot frames him in the corner of the window while she’s on the phone; instead of cutting between them, they occupy the same space, in ways familiar to anyone who ever got a jolt from a jump-scare. Suspense, indeed.

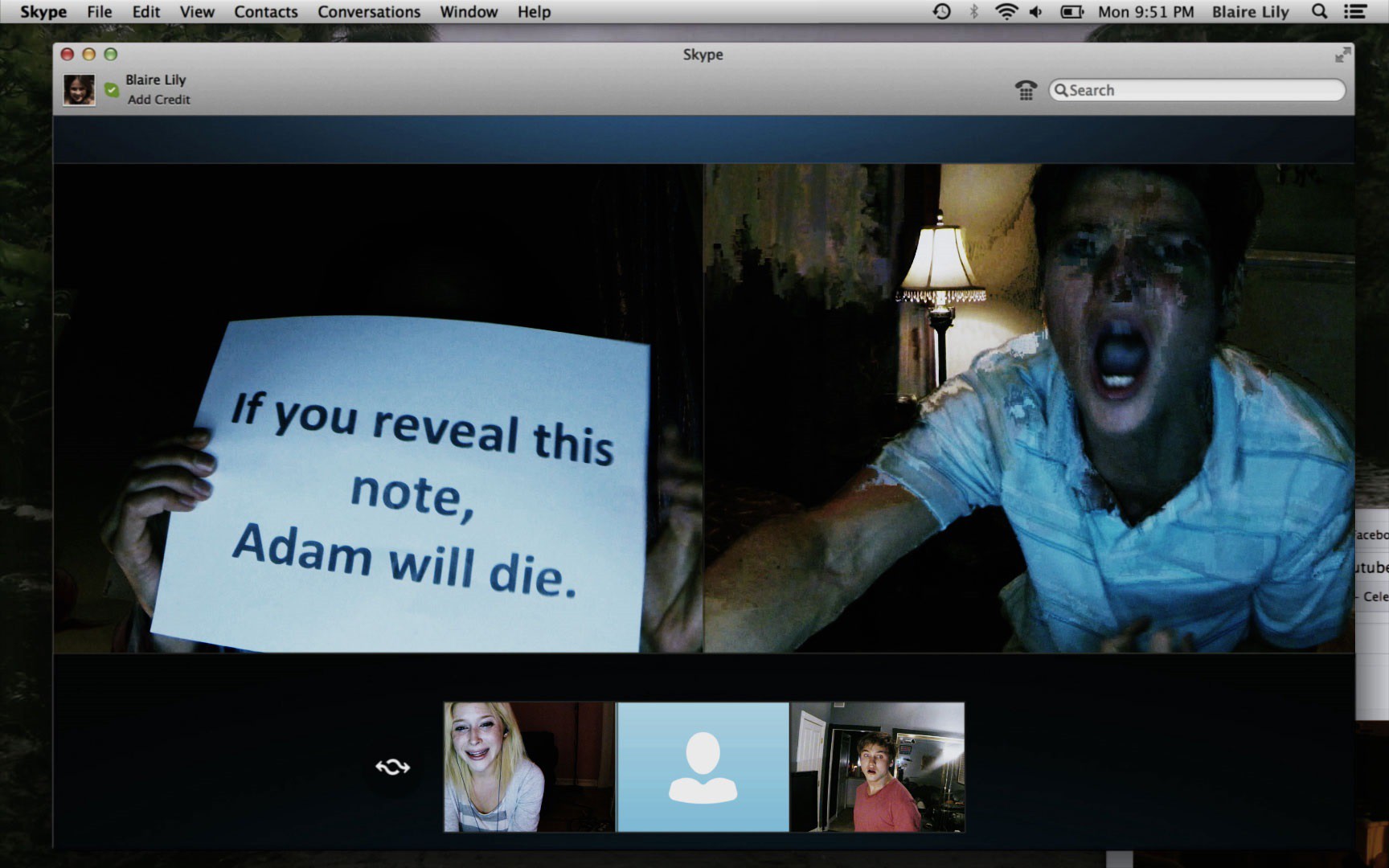

And then there are the split-screens. The most famous shows the wife making the call, the husband receiving it, and the Tramp breaking into the house. Bordwell notes that this serves to:

substitute for crosscutting: instead of giving us three shots, we get one, showing the plot advancing along different lines of action. These splintered frames function much like Brian De Palma’s multiple-frame imagery in Sisters, Blow-Out, and other films.

Later, as the stolen car barrels down the road, we catch a glimpse of his pursuers in the side-mirror, once again exploiting POV (in this case, the frantic husband’s) to both call up identification and to rather ingeniously keep the action moving in a way that propels us forward through the narrative and frame, rather breaking it up with cuts between subjects.

These formal techniques, now commonplace or even cliche (see the De Palma reference above, for instance), still seem startlingly original for 1913. But the narrative itself was anything but. Bordwell again:

If the plot sounds familiar, it’s probably because you know that one of D. W. Griffith’s most famous films, The Lonely Villa (1909) tells the same basic tale.There are still earlier versions, including one, The Physician of the Castle (Le Médécin du chateau, 1908), which may have inspired Griffith. The ultimate source seems to be a 1902 play by André de Lord, Au téléphone.

From cinema’s beginnings, working and reworkings of narrative are more the rule than the exception. Perhaps that’s even more true for genre pieces like Suspense and the horror / thriller / action entries to follow over the next century.

In a recent piece titled “America has a horror movie problem”, Greg Cwik bemoans what he perceives as a lack of originality in the current crop of genre offerings. He makes several valid points — and briefly goes to bat for the often and unfairly derided Unfriended, my favorite found-footage-inspired movie in a long while and a fun treatment of that same split-screen technique, made recognizable for a new generation — but there’s a still a sense throughout the piece that the trend he assails dates back a full 100 years.

The well-received Don’t Breathe is, Cwik writes, “by no means bad, and has certain admirable qualities … but we’ve seen — and heard — this before.” Indeed we have. But I’m not convinced this is a negative, or even avoidable. The re-routeing and re-consideration of genre tropes are acts that lie at the heart of these kinds of creations; I’m not even sure they’re avoidable, without ceasing to be genre pictures.

In fairness, Cwik raises up two films — The Witch (which I’ve seen) and The Love Witch (which I haven’t) — as exceptions. Rather than simple retreads of formal and narrative tropes, pastiche and homage trafficking in things audiences have been mercilessly trained to recognize and appreciate in and of themselves, each of these films “uses its influences to say something. That’s what homage should do.”

Fair enough, but a look at something like Suspense also indicates that formal innovation and narrative re-purposing go hand in hand. Weber didn’t set out to tell a new story, but rather to use the camera to tell an old story in a way that felt new.

Cwik could, and I assume would, respond that this is the point: the films he feels fall short do so for precisely this reason, their failure to feel new.

That’s subjective, of course, but it’s a familiar enough sense. But even in 1913, filmmakers were poaching stories from a decade prior for their treatments. In the case of Suspense, there were layers still to uncover. It seems likely this will always be the case.

You can watch Suspense below on YouTube: