The road trip belongs to an incredibly particular technological moment.

There must be an element of protraction; it must take long enough to get from point A to point B to generate enough plot to keep the opening and closing credits 90-plus minutes apart.

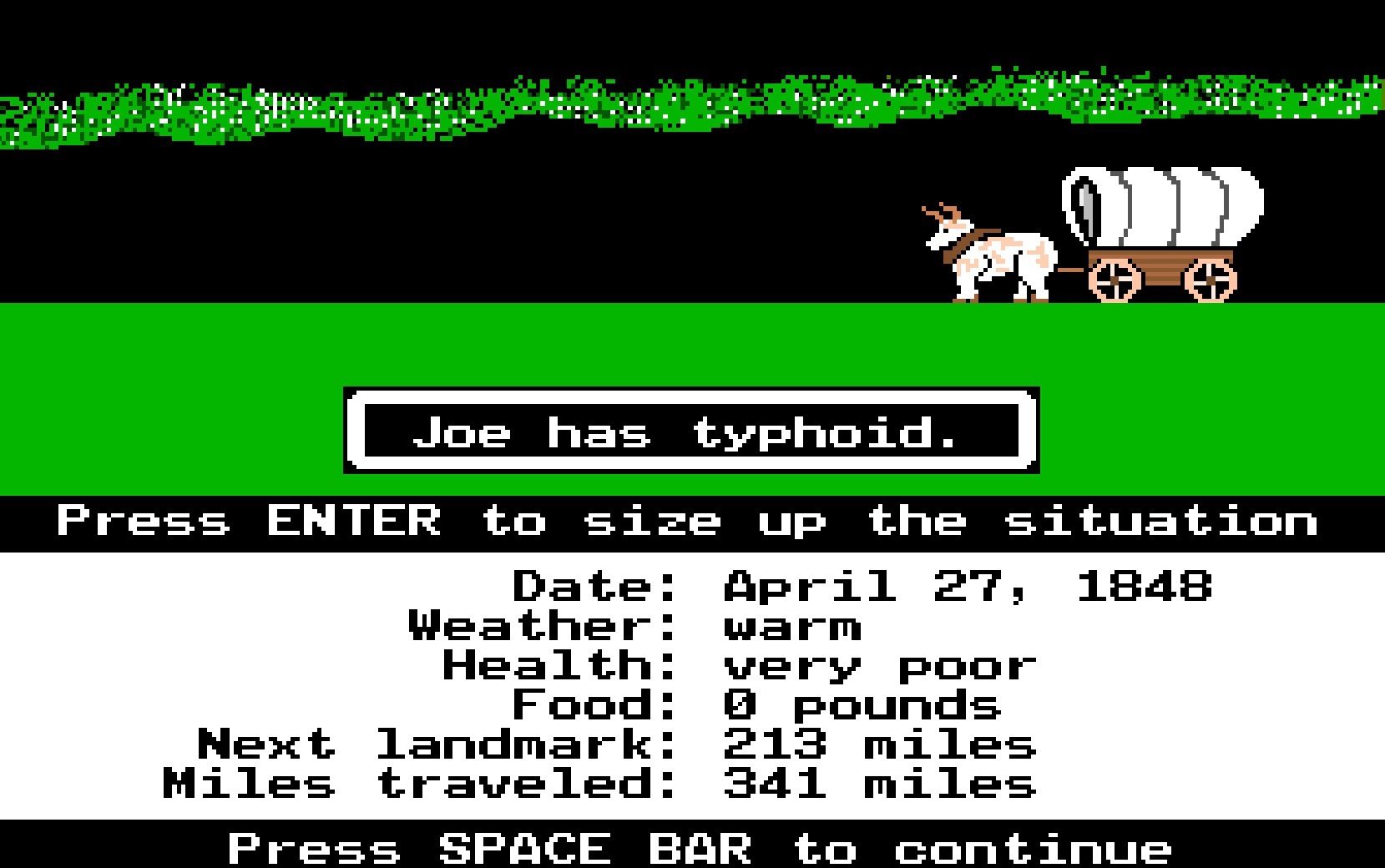

But there also must be an element of ease which makes the trip an escape from the travelers’ everyday lives, not a permanent and irreversible shift. The Joads were not quite going on a “road trip,” nor were the thousands of families who schoolchildren killed off playing Oregon Trail.

Before the post-war automobile production boom in the United States, the road trip movie couldn’t exist. What is—or was—its endpoint? Genres usually are born more suddenly than they die, but if Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World doesn’t mark the end of the genre as a real form of life (as opposed to a self-referencing, self-replicating fantasy machine), it can mark one of the logical endpoints of it.

Before the post-war automobile production boom in the United States, the road trip movie couldn’t exist. What is—or was—its endpoint? Genres usually are born more suddenly than they die, but if Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World doesn’t mark the end of the genre as a real form of life (as opposed to a self-referencing, self-replicating fantasy machine), it can mark one of the logical endpoints of it.

In its extended form (the 270-minute The Trilogy version, which splits the movie into three feature-length films; a 300-minute, 2-part version recently toured as part of a Wenders’ retrospective and is rumored to have a Criterion release in its future), Wenders’ film is the road trip at the end of its life.

Released in 1991 and set in 1999, it feels like the last gasp of a world where points on a map are close enough to make travel possible, but far enough away to make them distinct, to make it still possible to tell a story about the getting there.

In fact, remarkably little attention is paid to the travel. Most of the “road trip” elements take place in the first 2-and-a-half hours, as Solveig Dommartin (who co-wrote the script with Wenders) tracks down William Hurt, a fugitive with whom she falls in love. But outside of their ‘meet cute’, a segment in which Dommartin gives Hurt a ride to help him escape from mysterious bounty hunters, all the travel of her chase takes place in brief shots of boats, of cars, or of planes as her former lover (Sam Neill) narrates.

hours, as Solveig Dommartin (who co-wrote the script with Wenders) tracks down William Hurt, a fugitive with whom she falls in love. But outside of their ‘meet cute’, a segment in which Dommartin gives Hurt a ride to help him escape from mysterious bounty hunters, all the travel of her chase takes place in brief shots of boats, of cars, or of planes as her former lover (Sam Neill) narrates.

As all points on the map become neighbors to all the others — and I’m using the term as much in its mathematical sense as its commonsense one — each individual place they visit becomes essentialized. Removed from its place in Japan as a whole, the traditional inn Dommartin and Hurt visit becomes merely a magical place where the mystical owner uses vague ancient  rituals to heal Hurt’s failing eyes. The trip to Japan serves as an essential turning point in the movie, occurring roughly 2 hours in and marking a transition from European ports of call like Germany and America, which still manage to retain some uniqueness, to Eastern locations which increasingly stand in for the magical other-place.

rituals to heal Hurt’s failing eyes. The trip to Japan serves as an essential turning point in the movie, occurring roughly 2 hours in and marking a transition from European ports of call like Germany and America, which still manage to retain some uniqueness, to Eastern locations which increasingly stand in for the magical other-place.

As the film moves into its final third (The Trilogy is so clearly divided into thirds that the credits run in their entirety before each section), it reaches the final stage of a terminal acceleration. It settles into the Australian outback as an EMP blast wipes out all technology, and aboriginal Australians begin to stand in for all sincere life. Whether or not Wenders’ depiction of indigenous Australians is essentialist or Orientalist (I’m not nearly informed enough to say for sure), they are really stand-ins for something else. They are the ultimate end of the “road trip” as such. Absolutely situated, unable to move from their place (several scenes center around them marking sacred spaces in the land so they are not destroyed by radiation), they are every point on the road the road trip travels down brought to a point.

After all, that is always the essential relationship of the stops on the road to the travelers on the road. For the travelers to travel down the road, everything along the side must stay still. And for those things to stay still, they must have their own frames of reference. As travel changes and those points become closer, the uniqueness of the places at which one can stop must shrink inwards. The magic secret that was located in a place now has to be located somewhere inside. What does that do to the road trip as a narrative idea?

The exhaustion of the movie, the sense that this is the “ultimate road trip movie” (to quote the tagline) — ultimate in  the sense of final — is what drives the colossal running time. One wonders if it is the increasing closeness of everything that has led to the stagnation of the second half of Wenders’ career; other than the documentary Buena Vista Social Club in 1999, he hasn’t made an acclaimed movie since Wings of Desire (1987).

the sense of final — is what drives the colossal running time. One wonders if it is the increasing closeness of everything that has led to the stagnation of the second half of Wenders’ career; other than the documentary Buena Vista Social Club in 1999, he hasn’t made an acclaimed movie since Wings of Desire (1987).

Maybe it’s time to reorganize how we think about Wenders’ films. It is easy to celebrate the brilliance of his early movies like Alice in the Cities, Kings of the Road, Paris, Texas, and a half-dozen others and ignore everything post-Wings of Desire as the result of a brilliant artist losing their touch. But maybe it is closer to an artist whose world shriveled up in the face of technological progress, and has spent half his career trying to recreate and recover it. Maybe it’s in that failure that we can understand the world better and more beautifully than in a nostalgic desire for his golden period.