Susan Oxtoby knows film.

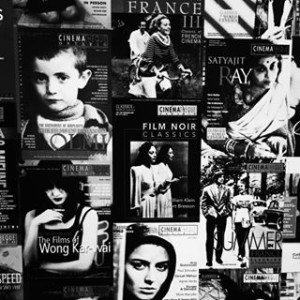

Over the course of her career, the current Senior Film Curator at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (Bam/PFA) has programmed countless series and retrospectives, introducing audiences to under-seen, rarely-screened masterpieces from throughout the world and across cinema history.

A filmmaker in her own right (her late friend Stan Brakhage charmingly provides her film All Fl esh Is Grass with the most Stan Brakhage-esque recommendation imaginable), Oxtoby’s passion for and commitment to cinema — its preservation and exhibition, its relevance to our lives and cultural memory — are evident.

esh Is Grass with the most Stan Brakhage-esque recommendation imaginable), Oxtoby’s passion for and commitment to cinema — its preservation and exhibition, its relevance to our lives and cultural memory — are evident.

Both were very much on display when she graciously agreed to sit down and chat about Bam/PFA’s first two months in its new location, what she’s most looking forward to this season, and what surprises future seasons might hold.

This is Part 1 of our interview: tune in tomorrow for a closer look at the challenges of film preservation, the role of archives in the modern world, and a curator’s thoughts on the “film vs. digital” debate.

(This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.)

_______

Rick Kelley: So it seems to me you have the world’s coolest job. What led you to enter the world of film curation in the first place? What was your path like?

Susan Oxtoby: In terms of curating films, programming films, that really began in a student film society at the University of Toronto. It was called the Innis Film Society – Innis was one of the 8 colleges in the School of Arts and Sciences system at the University of Toronto, but it was also where cinema studies as a program and discipline was based. And so I had actually gone through that cinema studies program at the University of Toronto and was in another degree, studying film production, and I realized I should get involved with the student film society because they were showing such great work.

And so there was a period of about 7 years – this is the essay answer! – where I was completing my second degree but I was also back at the University of Toronto showing this very impressive year-round program of largely avant-garde film, or art films. It was a Thursday night program, so that was where I got a sense of how to construct programs. Every year, we brought in about 15 visiting filmmakers, Canadians and Americans, some international guests, but usually it was working in the area of avant-garde film.

Then, my early jobs were actually in independent film distribution. In Toronto, there’s the Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, which is much like Canyon Cinema, the same kind of philosophy. So I worked in distribution for about 3 years representing independent work in an artist-run center and was always meeting with visiting film curators from all over the world, and helping them interpret this large collection of some 3,000 films, largely Canadian but also international in character. A position opened up at the very young Cinemateque Ontario, which is now TIFF Cinemateque. So I kind of joined and became a young film programmer for my first professional position in curating back in 1993 and stayed with that institution for 12 years and became the Director of Programming.

That was an interesting period because that was a young institution – I’d say for its first 15 years it kind of went from 0 to 60 in terms of becoming very well-known for its programming. Of course, I was working with the wonderful James Quandt, who was the founding Director of Programming and is still there as the Senior Curator. So that was great. And we really built it up. You know, we were modeling ourselves largely after the Cinémathèque québécoise in Montreal and, frankly, the Pacific Film Archive.

RK: It all comes full circle!

SO: It comes full circle. And so we were in very close contact with this international network of film archives, and we partnered a lot with the curatorial staff here at the PFA.

RK: So it was sort of a natural transition when you came over here. You already had the groundwork laid in some ways.

SO: Yeah. But that was how I got into programming. And, you know, from my early teens, I really got interested in foreign films. My parents were cinephiles, so I saw a lot growing up. [They] were really into films, concerts, interesting international travel. And I was growing up as a child of the ’70s, let’s say, in my university days, and that was when a lot of places would have the latest Fassbinder film, the latest new, contemporary Italian film playing in art houses around Toronto. So I very quickly got into following that as a major.

RK: And you made a few films of your own, too. You’re a filmmaker in your own right.

SO: I definitely studied film production and I worked with independent filmmakers for a couple of years, filmmakers in Toronto, either avant-garde filmmakers or documentary or narrative filmmakers. And then I have two 16 mm films that are in distribution.

RK: So, for those of us (like myself) who don’t really know, what is a day in the life of a film curator like? What do you, you know, do?

SO: [laughs] I think a lot of people think, “Oh, you spend your whole day watching films!” Actually, this is not the case.

We spend our days in correspondence, and, of course, as the head of our department, I spend a lot of time in meetings. And then I’m fortunate to see most of our programs, so I spend my evenings at the theater. But it’s interesting. When you’re dealing with contacts all over the world, I start my day very early, corresponding with Europe, and then of course the East Coast, and whatever I can get done by the end of the day in Pacific Standard Time. And maybe by the end of the afternoon, we’re working with contacts in Asia, trying to get those emails off …

RK: It sounds exhausting, actually!

SO: [laughs] Yeah, but you know, you work against the world’s time zones. I mean, it’s extremely varied. I love the fact that we’re in this new location, Bam/PFA, and that we have so many visitors coming in, like this chance to chat with you today or to host [filmmakers]. There’s a visiting filmmaker yesterday, Wang Bing from mainland China, who’s here in the Bay Area for a few days, and he wanted to come over and meet with our staff. So that was exciting. We’re not even hosting his work right now, he just wanted to come see our institution. It was fun to show him around the galleries, the couple of theaters and the outdoor screen, and talk about what we might be able to do in the future.

So that’s the thing. It’s been so exciting for us now to be in this new location meeting with so many visitors. It happens a lot, and in any given week we’ll have the guests that we’re bringing in for our programming but also meeting with the public.

I’m really delighted that in this spring semester, we’re offering some programs that are lecture screenings – the In Focus: The Role of Film Archives and this upcoming series of Japanese film classics – and that’s where I selected the programs we’re showing and invited guest speakers to come in and share their knowledge on specific film programs or topics. One of the things I think we do particularly well at Bam/PFA is the involvement of guests and specialists, from filmmakers to archivists to practitioners who might be editors or the wonderful academic talent here at UC Berkeley and beyond.

RK: How does the PFA build its collection? I know there were large donations back in the day, but how do things work now?

SO: Well, it’s very difficult for us to actually raise funds to go out and purchase prints. Some of our patrons are learning that it’s possible to make a gift that would go toward our film acquisition budget if it’s designated for that. But a lot of prints come in currently from film distributors who know they’re getting out of the business. [They] understand that we are an archive and that they can offer their prints to us and, if those prints are still in exhibition condition, we would take them in and be able to show them over time. So basically, donations from filmmakers and film distributors, acquiring films outright, [and] also working with other archives that might have recently worked on restoration … that’s the perfect time for us to acquire a new print.

We recently purchased a copy of The Seventh Seal from the Swedish Film Institute, and I’d love us to be doing as much of that as we can possibly manage, because it’s a great way to build the collection. We had some local donors who helped underwrite that, and it’s the perfect film for us to have in the collection. It will get screened a lot over the years. We had three very full programs [already].

RK: With the new location, did the move alter the programming, or change the audience, in any way?

SO: It has definitely changed the audience. Our numbers are really great. I think downtown Berkeley has … you know, I think there are more people going out for a bite and coming to the new Bam/PFA to see a film, look at the galleries. So it’s great. We’re now joining with all the other cultural venues based in the downtown core – the jazz festival or Berkeley Rep, Freight and Salvage or the new university theater …

RK: Sure. It’s very much in the community.

SO: It makes a big difference to be on the same block as BART. We’ve heard a lot from people who are just grateful we’re so much easier to get to. And then there are also all the restaurants, and just more night life at this end of the campus. So that really is great.

But I do think that just by launching this building, more people have found out about our programs and there’s been a great public response. The only thin g that’s

g that’s  really changed in our programming is that we’ve introduced some limited engagement films, so that’s a place where we might have three screenings of Rocco and His Brothers or, upcoming, we’re showing a contemporary Romanian film, One Floor Below. We’re showing that four times. The only other time that film has shown recently has been at Mill Valley. So it’s a chance to see a contemporary film from Romania, and there’s been a new wave of Romanian filmmaking that’s been highly recognized.

really changed in our programming is that we’ve introduced some limited engagement films, so that’s a place where we might have three screenings of Rocco and His Brothers or, upcoming, we’re showing a contemporary Romanian film, One Floor Below. We’re showing that four times. The only other time that film has shown recently has been at Mill Valley. So it’s a chance to see a contemporary film from Romania, and there’s been a new wave of Romanian filmmaking that’s been highly recognized.

We really wanted our inaugural season to be reflective of all the great strengths that we are known for, in terms of showing beautiful silent films with musical accompaniment or avant-garde film programs, or the focus on documentary filmmaking as always in our spring season. Plus complete retrospectives like the Maurice Pialat or the Jean Epstein series that’s on the screen right now. Upcoming, we’ve got the Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan, and that’s a rare chance to see his works to date in a complete retrospective. To my knowledge, the only venue in the U.S. that’s done a complete Ceylan series is MoMA in New York about a year and a half ago.

So our hope is that we will be on a closer to year-round schedule on our five-day-a-week program when the museum is open, which means we’re going to be showing more films than we were at our old location. And by allowing some of those to be repeated, make it a little easier for the public to get more of those films in their schedules.

It’s hard when you only show something once. I mean, we do, and they do very well, but giving more chances, more opportunities to see particular programs will help us build our membership.

RK: One of the more notable projects in the old location that you were involved in was “Discovering Georgian Cinema”, and I was curious first of all how that came about, and what you think is vital about showing underseen or even never-seen films?

SO: “Discovering Georgian Cinema” was such a wonderful opportunity for me personally, because I had no background in Georgian film before I took on that project. But I think I did have the right kind of background to take on such a complex program because of my connections in the international archival community. So it was this wonderful opportunity and something I know I’ll be returning to, doing more with this area of cinema.

But it started from the point that Bam/PFA’s film collection has, in fact, the largest collection of Georgian films in North America, and I may be right in saying the third largest collection outside of Moscow.

RK: That’s amazing. And similarly true of Japanese films as well, right?

SO: Yes, that is true. Our Japanese collection is a very important study collection, and a portion of it would be of exhibition quality. But it’s definitely very important for researchers, especially researchers who might not have the Japanese language as a capability.

With the Georgian project, I received a grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation to allow me to visit a number of archives and to visit Georgia and make connections with the local film community there. So I went to Tblisi, I went to Berlin where there’s a very large collection, and to Moscow, as well as archives in Europe like Amsterdam and Toulouse. And I was partnering on this project with the Museum of Modern Art. It was so important to be working with MoMA because that really increased the profile of our series. It was about 57 different programs here in Berkeley, which is bigger than anything we’ve done. And [it was] an opportunity to bring in filmmakers from Tblisi or from Europe, and experts on Georgian cinema. So it was a great learning experience

RK: Is that one of the key roles an institution like the PFA plays, to bring these kinds of things to new audiences?

SO: Absolutely. And we thought carefully about calling it “Discovering Georgian Cinema”, but I think it is absolutely the case that a lot of these films are completely unknown here in the U.S. If you actually went through to see how many of these films had never been shown by any institution in North America, there would be a good percentage of them represented in that category.

RK: I’m hard-pressed to name too many Georgian films.

SO: [laughing] Exactly. But it is a beautiful body of work. And of course in many different types of ways.

But we were able to do a lot of different things with that program. I think certainly to show enough work from the silent era. Soviet Georgian filmmakers really were doing very inspired silent films. And then there’s the period from about the mid-’50s through the ’80s, which is kind of a beautiful period of narrative cinema and development, in terms of Georgian filmmakers perhaps being critical of the Soviet regime and their relationship within the Soviet Union. But also always making works that were very much about the history of Georgia, the spirit of the Georgian people, the music and poetic and dance traditions.

I’m sure we’ll circle back and present more of these films another time round. You know, we could focus on particular directors or … I think contemporary Georgian film is really exciting right now. Things are coming together and there are a lot of really creative young filmmakers, so I think it’s an area of the world to watch.

RK: Earlier today, I was making a list of all the different filmmaker retrospectives you’ve been involved in over the course of your career, and I eventually just gave up, because there were too many. And I just wrote, “Pretty much everyone I’ve ever heard of.”

But are there series you remember particularly fondly? Perhaps in terms of exceeding your expectations for audience engagement or for really lively discussions?

SO: Many, many. That’s what keeps me going – the relationship between the guests we bring in and the audience response to their work. But I’m a real generalist. I mean, I do have specialties – avant-garde film and now Georgian cinema for sure are two of those. But I really do enjoy the fact I’ve usually been with institutions that show 400+ films a year, and so I’ve always been researching in an area that’s new to me. And I think you need to be a generalist in a lot of ways. I find that very exciting, and I’m constantly learning from the films I’m involved in selecting, but also from my colleagues.

One area I want to come back to – and I haven’t been doing this in the last decade that I’ve been in Berkeley – but I’m fascinated by abstract cinema. Which is squarely within the avant-garde tradition. But I did a series in Toronto called “Abstract Cinema: A Century of Light Play”, and it brought together French films from the 1920s, some German avant-garde film. It was a chance to bring in experimental filmmakers to present their work and show it. One area of cinema that I love, and I think it’s also related to my time going to music concerts, is just films that deal with rhythm and color in a very abstract way. And maybe it’s because I’m somewhat challenged when it comes to narrative cinema. [laughter] I might forget how a story ends, but I’ll remember the mood and atmosphere quite well.

So I would love to start introducing kind of an ongoing series that looks at abstract cinema. I think it’s perfect for us, because we’re also an art museum, and I think that there’s crossover … whether it’s music, poetry, or fine art, [audiences] can connect to that kind of cinema very well. There’s just a wealth of wonderful filmmaking that could be shown. That’s something I’d love to do.