The events of May 1968 exist in memory, of course, but whose memory, and how? The overlapping texts of Philippe Garrel‘s Regular Lovers, Bernardo Bertolucci‘s The Dreamers, and Olivier Assayas’ Après mai offer clues.

Amid all the recollections of ’68 in the past few weeks — whether extolling the energy of a revolutionary moment or gleefully trumpeting its failure, or something in between — I’ve been surprised how many people in my generation, in the U.S., are at a loss for context.

Within some radical circles (in the Situationist-inflected sloganeering of Crimethinc, say, or the enduring wheatpaste aesthetic of protest movements) and among some cinephiles (those who remember, first or second or third-hand, the shutdown of Cannes and the long shadow of that period’s mythology) this is sometimes less the case. But on the whole, explanation seems required, 50 years out.

Within some radical circles (in the Situationist-inflected sloganeering of Crimethinc, say, or the enduring wheatpaste aesthetic of protest movements) and among some cinephiles (those who remember, first or second or third-hand, the shutdown of Cannes and the long shadow of that period’s mythology) this is sometimes less the case. But on the whole, explanation seems required, 50 years out.

This lack of reference points is a function of cultural and political distance, but also of the multi-pronged character of the events themselves. The sense of something lost in translation has hilariously informed many pieces this month, only adding to the confusion. A recent ABC write-up informs us that:

Events began in the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris in the western suburbs of the city, where there were a series of student occupations and strikes over, among other things, the right for male students to visit the women’s dormitories.

Several paragraphs later, we learn that “[A]s the protests unfolded, the students’ grievances were greeted sympathetically by workers elsewhere in Paris and throughout much of French society.”

The reader wonders, then, at this French insurrectionary miracle, where factories were shut down and a general strike called amid truncheons and barricades, all in defense of that most noble struggle, the undying integrity of collegiate horniess. The intended point – that demands for social and political change, largely springing from youth revolt, coalesced with labor’s aspirations in a time of widespread questioning of norms and global tumult – is so elided that we end up with a comic shorthand: Sex strike! (Not to say that fucking isn’t worth setting cop cars on fire for. Bien sûr.)

The reader wonders, then, at this French insurrectionary miracle, where factories were shut down and a general strike called amid truncheons and barricades, all in defense of that most noble struggle, the undying integrity of collegiate horniess. The intended point – that demands for social and political change, largely springing from youth revolt, coalesced with labor’s aspirations in a time of widespread questioning of norms and global tumult – is so elided that we end up with a comic shorthand: Sex strike! (Not to say that fucking isn’t worth setting cop cars on fire for. Bien sûr.)

But for the French, like most of Western Europe, even the encapsulating phrase “the events of May 1968” is redundant, implying a cultural memory that doesn’t need so much supplement to situate itself. Les événements de mai becomes les événements, or simply mai, avant- or après-. (This specificity leads me to use the French title of Assayas’ film; the English rendering Something In The Air carries with it a melancholy whiff of tear gas and a vague sense of the ethereal, but loses everything else.)

When, two days after his election, Sarkozy pledged to “liquidate the heritage of May ’68,” no one needed to ask what he meant – though how that weasel managed to contort his own memory and attribute “the cult of money as king, of short-term profit and speculation” to the soixante-huitards remains mysterious. (This is not, as a rule, the charge one would expect eternally-vacationing rat-faced billionaires to level against the students and strikers a generation gone.) The election of Macron, France’s first President born after 1968, signals May’s further receding: “After briefly floating the idea of a national celebration, Mr. Macron retreated, “ writes Laura Cappelle in the Times. “Extolling 1968’s spirit of freedom and anticapitalism was a juggling act too far for a liberal president facing strikes of his own.”

So 1968 is both epochal and hazy, either held in impossibly lofty esteem by an organized left who were largely the targets of its ire, eyed suspiciously by the pragmatic shopkeepers and homeowners who once fought the police, blamed or celebrated for everything from liberal identity politics and “political correctness” to dogmatic neo-Marxism, or ignored altogether. The question of whether to celebrate a 50-year return of the not-quite repressed is also to ask what and why we remember.

Film, of course, remembers. Between the Langlois affair, the cancellation of Cannes, and the active participation of cineastes in the city where cinema was born, film was central to May: the events were certainly one of the most videographed “orgasms of history” we have, a sort of lived memory even in the moment. But if we consider cinema itself as a collective memory bank and an art form both dependent on structurally time and in protracted conversation with itself, we find ourselves in a unique situation.

Film, of course, remembers. Between the Langlois affair, the cancellation of Cannes, and the active participation of cineastes in the city where cinema was born, film was central to May: the events were certainly one of the most videographed “orgasms of history” we have, a sort of lived memory even in the moment. But if we consider cinema itself as a collective memory bank and an art form both dependent on structurally time and in protracted conversation with itself, we find ourselves in a unique situation.

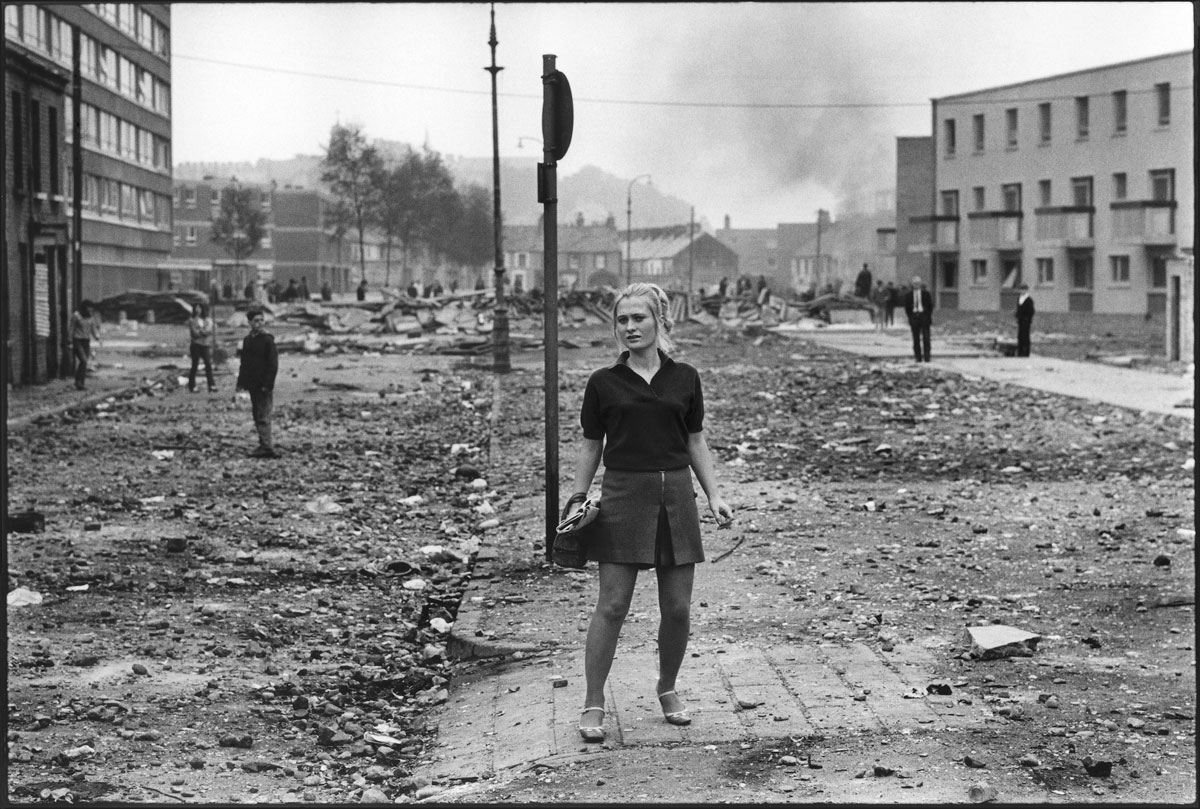

The images from the barricades galvanized the would-be revolution, documented it, processed it, and continue to provide the basis for dialogues of all sorts. Indeed, some of that documentation came from Phillipe Garrel, whose Actua I, once thought lost, Godard thought the best of the “actualities” captured on the street, and which he restages in Regular Lovers a generation later. (This esteem may or may not have something to do with the fact that much of it was shot from the passenger seat of a Godard’s Alfa Romeo, with his 35 mm camera: according to Jackie Raynal, Garrel’s editor and assistant director, “Because of the Alfa Romeo, the police left them alone.”)

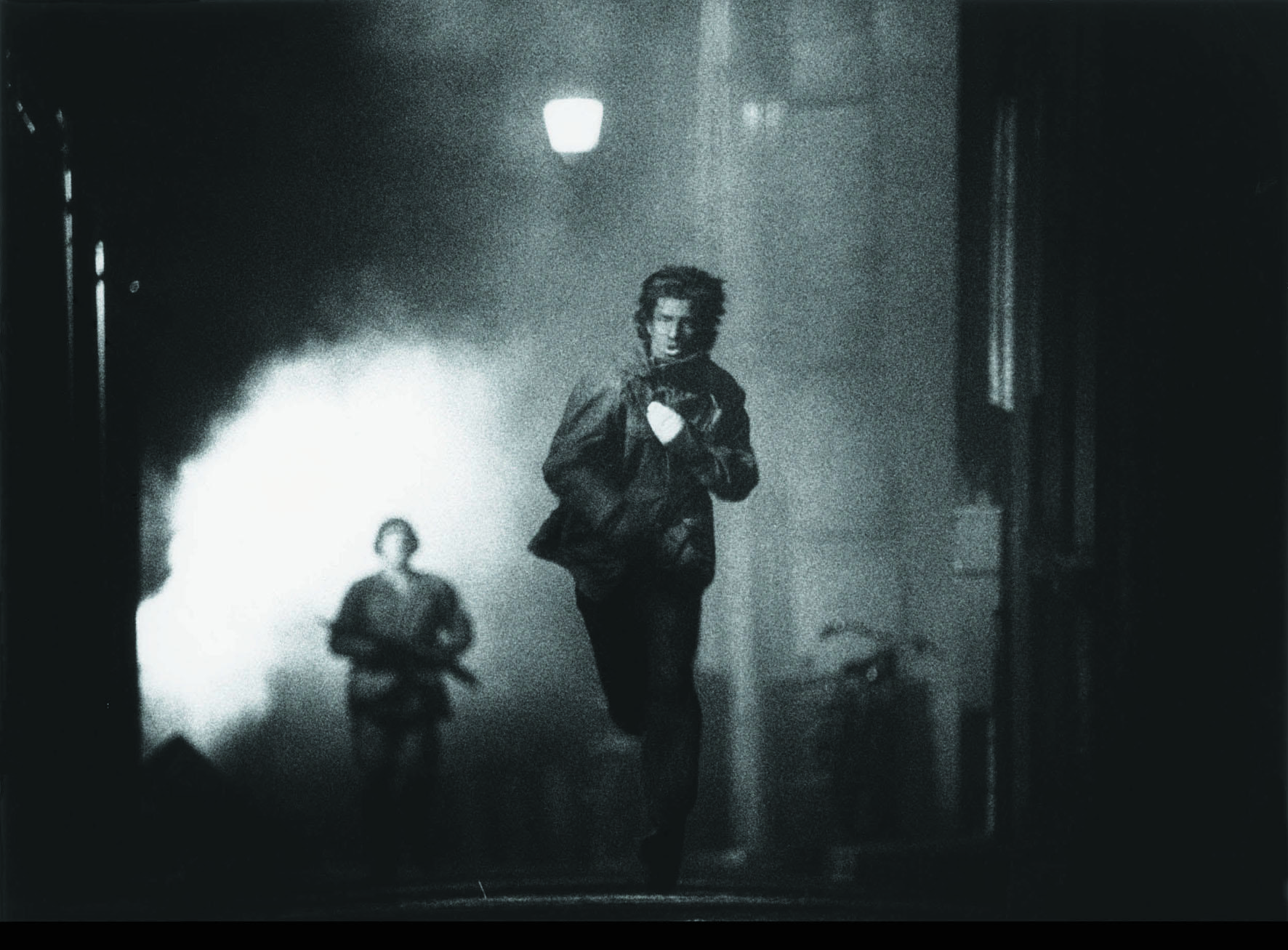

It’s a tidy encapsulation of 1968’s filmic time warp: Garrel would imagistically revisit this fraught moment of his youth by filming scenes on streets he himself originally filmed, though this time with his son Louis as his muse and stand-in. The same Louis Garrel who had, just the year prior, starred in fellow ’68 traveler Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, placing Garrel’s film in explicit conversation with it, and who would in 2018 portray Jean-Luc Godard in Hazanavicius’ stillborn idiocy Godard, Mon Amour.

In fact, at Regular Lovers‘ Venice premiere, the two Garrel’s amusingly recounted how the film was made: to cut costs, they intentionally followed Bertolucci’s footsteps like an old Hollywood B-movie, reusing costumes and sets. And even extras — the young Garrel is recounts with bemusement that he found himself staring down the same flics across the same barricades. The memories intertwine in their retellings and their images.

In fact, at Regular Lovers‘ Venice premiere, the two Garrel’s amusingly recounted how the film was made: to cut costs, they intentionally followed Bertolucci’s footsteps like an old Hollywood B-movie, reusing costumes and sets. And even extras — the young Garrel is recounts with bemusement that he found himself staring down the same flics across the same barricades. The memories intertwine in their retellings and their images.

What becomes remarkably clear from these films about 1968 — along with Assayas’ narrative of missing the revolution by a year — is the degree to which cinema provides an inroad to memory and identity for this generation, in this time and place. For U.S. audiences, it’s music that largely plays this role; the opening strains to Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth”, Hendrix’s “All Along The Watchtower”, or Steppenwolf’s “Born To Be Wild” situate us, with a groan, within the eternal tundra of Boomer nostalgia. (The Big Chill is stands unchallenged in its self-satisfaction, in its wisdom that nothing new is possible, as the champion of this eschatology of preciousness.)

For the 1968 generation reflected in Regular Lovers, The Dreamers, and Après mai, there’s something different going on in the conversation. We’ll feel out the uneven edges and remaining possibilities of its memory in part 2.