In a world of near-constant commercial imperatives, the library’s very existence is something of a miracle. It’s easy to forget just how rare it is to simply exist in a space where you aren’t expected to purchase something until you’re standing in one. I mean, you can just take the things! And, instead of chasing you, the people are actually pleased you took them, and politely ask that you bring you them back sometime soon! How odd.

Reading about the new indie streaming service OVID.TV (slated to launch in March and featuring titles from “six different independent film distributors — Bullfrog Films, Distrib Films US, First Run Features, Grasshopper Film, Icarus Films, and KimStim,” according to IndieWire) made me reflect on the public library. This is no slam on OVID.TV or any paid service, per se. With the demise of FilmStruck, a new streaming service offering films from “Chantal Akerman, Michael Apted, Nikolaus Geyrhalter, Patricio Guzman, Heddy Honigmann, Chris Marker, Ross McElwee, Bill Morrison, Raoul Peck, Jean Rouch, Wang Bing, and Travis Wilkerson” is certainly welcome. And of course, the cinephile-beloved FilmStruck is itself set to be reincarted, in a fashion, joining MUBI, Fandor, Amazon, Netflix, Shudder, and who knows what else, dotting the ever-shifting landscape of information transfer, CRM segmentation, and contractual agreements once known as “movie-watching”.

You could spend a fortune on all that. And you might! Then there are the less legal avenues, from questionably proprietary YouTube uploads to out-and-out file-sharing.

Which brings us to Kanopy. Many public libraries have long had impressive film and video collections (and still do, now adding Blu-ray to the mix), but the vast radness of their streaming selections is something I’ve only recently come to appreciate. Libraries that offer Kanopy to anyone with a library card are doing something important in terms of public access to cultural history in the digital age, and something libraries are uniquely positioned to do: stripping away the flattening sameness of streaming. It’s our paradox, which became more acutely felt and articulated after FilmStruck called it quits – what Joana Scuts termed “a slow erosion of cultural heritage under the guise of infinite availability.” Speaking to the central problem of corporate curation, Richard Brody wrote that “the best analogy for, and the best use of, streaming video is as a supplement to new releases, particularly of films that aren’t likely to get wide theatrical distribution:

Streaming puts the low-budget, independent, or foreign film on the same footing of wide availability as a studio tentpole film. But when it comes to classics, the era of streaming is as the days of repertory theatres—with the difference that, then, the limits were technical as well as financial. Film prints and projectors are costly and cumbersome. Now the limits are those of manufactured scarcity in the guise of abundance, manufactured dependence marketed as freedom. Consumers have been weaned off disks with the promise of convenience, of weightlessness, spacelessness, infinite portability, and a large (but unstable) library of offerings. In exchange, they’re tethered to the mothership for good.

In some sense, Kanopy is simply a different mothership, but anyone who genuinely considers it would almost certainly prefer to board the one steered by the public library, which is at the very least less likely to explode on a whim. (Funding, of course, is a different matter.)

On a practical level, there’s just something revelatory about scrolling through. Kanopy services differ regionally, but from where I’m sitting, I can watch nearly the entirety of the A24 catalog. Frederick Wiseman‘s documentaries are nearly all here, from Titicut Follies to 2017’s Ex Libris (about the New York City Public Library, appropriately enough). Yesterday, as news of Jonas Mekas’ death at 96 and appreciations of his astounding legacy filled my social media feeds, I took the opportunity to watch him in conversation on “Screening Room”, a Boston public access show that ran for 10 years and featured most of the luminaries of experimental (or, as Mekas prefers, independent) cinema. Kanopy has episode after episode: Mekas, Bruce Baillie, Brakhage, showing their work and art they admire or that influenced them, wearing ugly 80s pants and saying things like, “God created the artist to make the work, but God also created the archivist for the outtakes.” It’s delightful.

On a practical level, there’s just something revelatory about scrolling through. Kanopy services differ regionally, but from where I’m sitting, I can watch nearly the entirety of the A24 catalog. Frederick Wiseman‘s documentaries are nearly all here, from Titicut Follies to 2017’s Ex Libris (about the New York City Public Library, appropriately enough). Yesterday, as news of Jonas Mekas’ death at 96 and appreciations of his astounding legacy filled my social media feeds, I took the opportunity to watch him in conversation on “Screening Room”, a Boston public access show that ran for 10 years and featured most of the luminaries of experimental (or, as Mekas prefers, independent) cinema. Kanopy has episode after episode: Mekas, Bruce Baillie, Brakhage, showing their work and art they admire or that influenced them, wearing ugly 80s pants and saying things like, “God created the artist to make the work, but God also created the archivist for the outtakes.” It’s delightful.

The curatorial impulse shows up in the subject groupings: Films Directed By Women (which I’ve repeatedly groused isn’t available on other platforms, and which any #52FilmsByWomen enthusiast should value); a robust LGBTQ+ category; Must-See Classic Films and Film 101, a primer for many of the very titles in danger of being washed away by the streaming tide; Criterions aplenty, to fill the gap FilmStruck left. There are Sundance and NYT Staff picks, shorts, early film, and more. And this is to say nothing of the documentary and educational offerings, which focus on language, history, philosophy, and the arts. It’s as expansive as any library, and as free. There’s a practical constraint — a set number of “credits” for users to cash in — but it’s far, far better than nothing. (The Berkeley library sets this at a mere seven per account, unfortunately, though that still is seven more than you might otherwise have. Meanwhile, the L.A. Public Library allows users to watch as many Criterion titles as they’d like.)

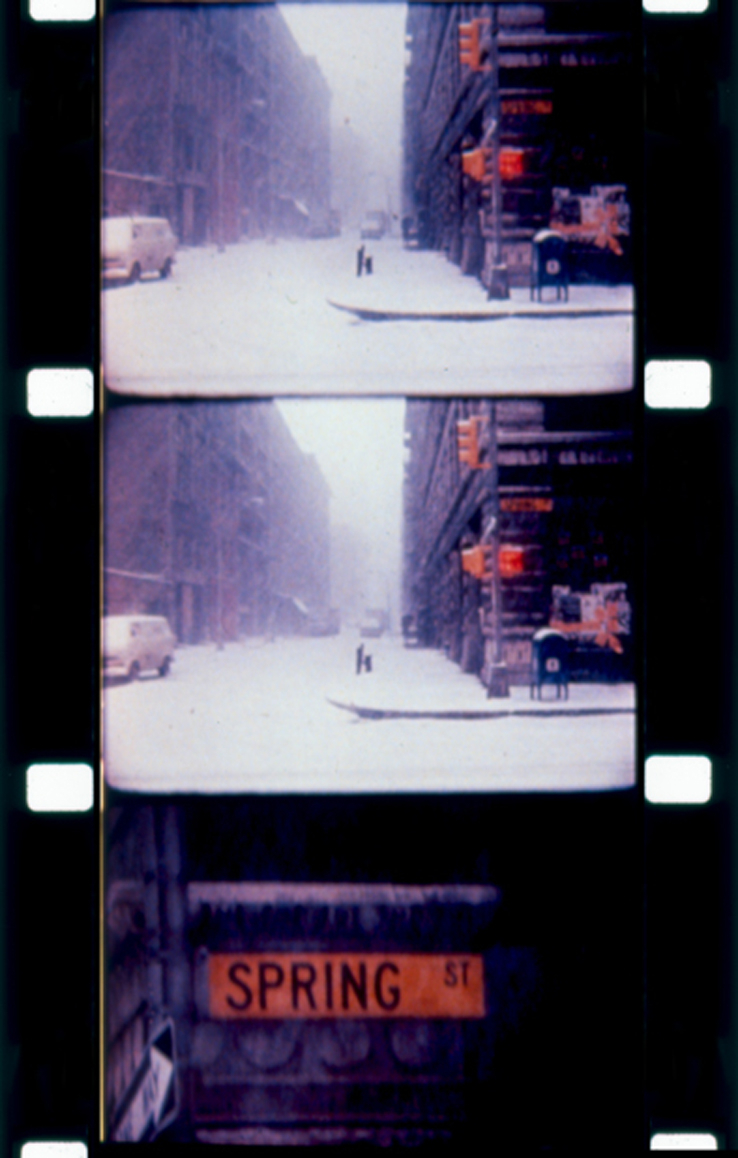

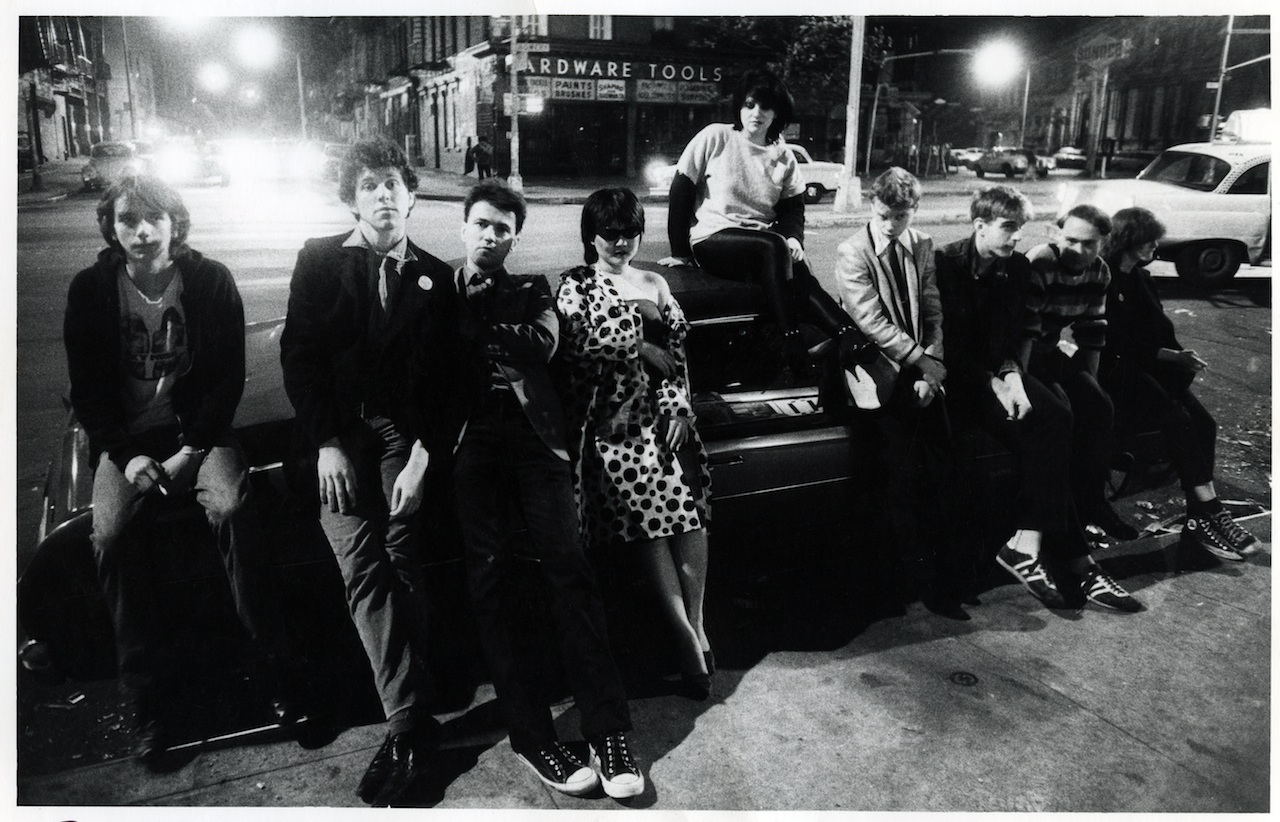

Most recently, I finally watched Celine Danhier‘s Blank City, an engrossing portrait of No Wave that I’ve been trying to lay hands on for a while. It’s fantastic and vital, mixing archival footage with snippets from No Wave artists, anchored by contemporary interviews with those who came out of the scene or were scene-adjacent: Jarmusch and Lurie and Buscemi and Waters, Lydia Lunch, Vivienne Dick, Richard Kern, Nick Zedd and the Cinema of Transgression representatives (as well as those still pissed they ever got lumped in). James Chance is there, tweaking about, and a baby-faced Thurston Moore peeks out from the back of an old photo. We get conflicting assessments of Basquiat and Wild Style‘s LES panorama at the moment of hip-hop’s birth. It’s as gripping a depiction of bombed-out NYC as you can get, and I couldn’t help thinking how weird it would feel to pay Jeff Bezos to watch it.

Most recently, I finally watched Celine Danhier‘s Blank City, an engrossing portrait of No Wave that I’ve been trying to lay hands on for a while. It’s fantastic and vital, mixing archival footage with snippets from No Wave artists, anchored by contemporary interviews with those who came out of the scene or were scene-adjacent: Jarmusch and Lurie and Buscemi and Waters, Lydia Lunch, Vivienne Dick, Richard Kern, Nick Zedd and the Cinema of Transgression representatives (as well as those still pissed they ever got lumped in). James Chance is there, tweaking about, and a baby-faced Thurston Moore peeks out from the back of an old photo. We get conflicting assessments of Basquiat and Wild Style‘s LES panorama at the moment of hip-hop’s birth. It’s as gripping a depiction of bombed-out NYC as you can get, and I couldn’t help thinking how weird it would feel to pay Jeff Bezos to watch it.

Not that Kanopy is above the “Because You Watched …” algorithm that increasingly defines our relation to our machines. Blank City prompted recommendations for Rumble, the new doc about the influence of American Indian musicians on rock n’ roll, and Salad Days, about the birth of Dischord and post-hardcore in DC. Perhaps I might want to check out Jarmusch’s Permanent Vacation, which Sam wrote about eloquently a year ago (and in which I did know the cast had to move a sleeping Jean-Michel Basquiat around the room to keep him out of the shot). Or Susan Seidelman‘s Smithereens, or Bette Gordon‘s Variety?

The thing is: yes. Yes, I might. The last time I logged in to Netflix, my enthusiasm for Mystery Science Theater led to a recommendation to check out their apparently quite similar production, Voltron: Legendary Defender. With all due respect to the Super Robot, I think I’d rather be at the library.