It’s a platitude to say that emerging technologies inform our fiction. How couldn’t they? The raw material of everyday experience – our buildings, schools, livelihoods, family structures, routines, modes of communication – has always weaseled its way into cultural production, realist or speculative. The very ways we capture and represent our experience shift with each new development, and so do the content and form of the stories we tell and consume. It will surprise no one reading this on a phone that phones themselves are having something of an inevitable moment. 2016’s millennial action narrative Nerve and last year’s prickly Ingrid Goes West indicate some of the reasons why.

The emphasis, in itself, is nothing new. High art or low, schlock or masterpiece, we’ve been fed a steady cinematic diet of people on the phone. (Lois Weber’s tri-furcated Suspense (1913) generates most of its, well, suspense from a woman on the phone and a threatening man at the door. We will see this more than a few times in the following 105 years.)

The emphasis, in itself, is nothing new. High art or low, schlock or masterpiece, we’ve been fed a steady cinematic diet of people on the phone. (Lois Weber’s tri-furcated Suspense (1913) generates most of its, well, suspense from a woman on the phone and a threatening man at the door. We will see this more than a few times in the following 105 years.)

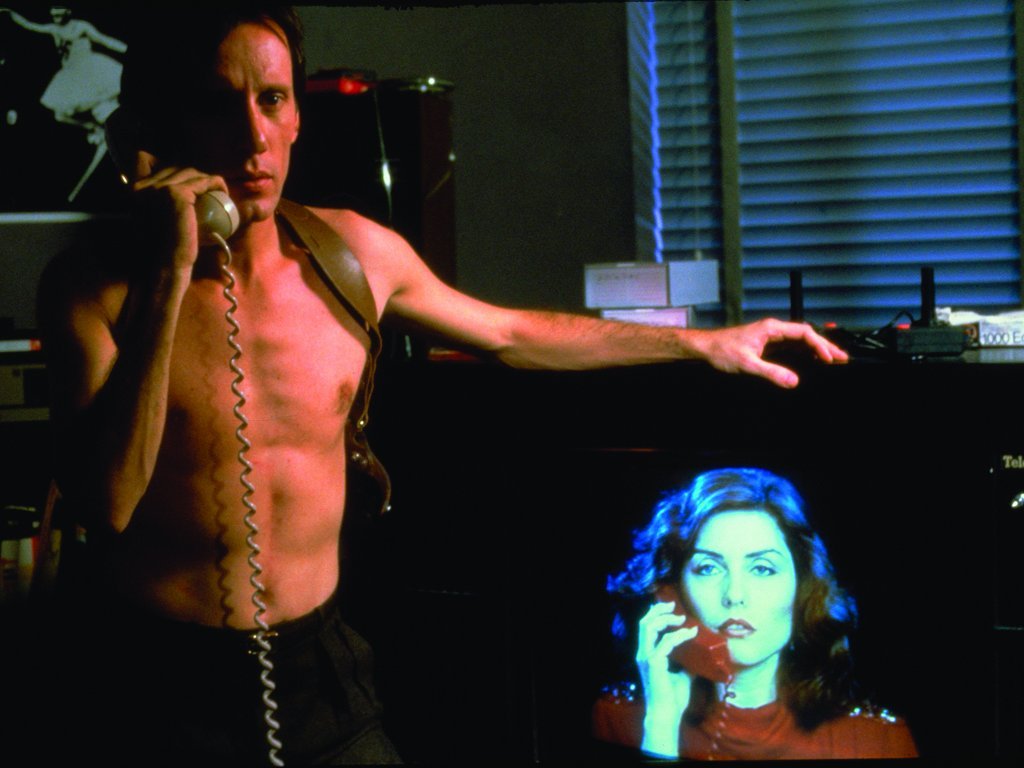

The ubiquity of various telecom devices – and their resulting paranoias, alienations, or possibilities for escape/subterfuge – is a sci-fi trope, of course; Star Wars or Trek or Blade Runner or 2001, the pervasive screens of Videodrome, Jack Palance‘s uncomfortably close videographic mouth in Cyborg 2, the comically large phone deployed by a comically large Rainer Werner Fassbinder in Kamikaze ’89. Hand-held space-age devices, glimmering screens that allow for proto-FaceTime interactions, telepathic  communication, AI … these are all familiar background elements, the sometimes literal wallpaper of the past’s dreams of the future, which, as Nick Pinkerton wrote about Kamikaze, “tells us more about the moment it was made than the future it imagines.”

communication, AI … these are all familiar background elements, the sometimes literal wallpaper of the past’s dreams of the future, which, as Nick Pinkerton wrote about Kamikaze, “tells us more about the moment it was made than the future it imagines.”

In less speculative contexts, the devices themselves are enlisted for symbolic reasons, giving us a sense of the characters and their relations – Gordon Gecko’s monstrosity in Wall Street, for instance, is funny now, but it’s clearly meant to give a sense of who he is, how his identity is constructed and how he functions in the narrative world we’re encountering.

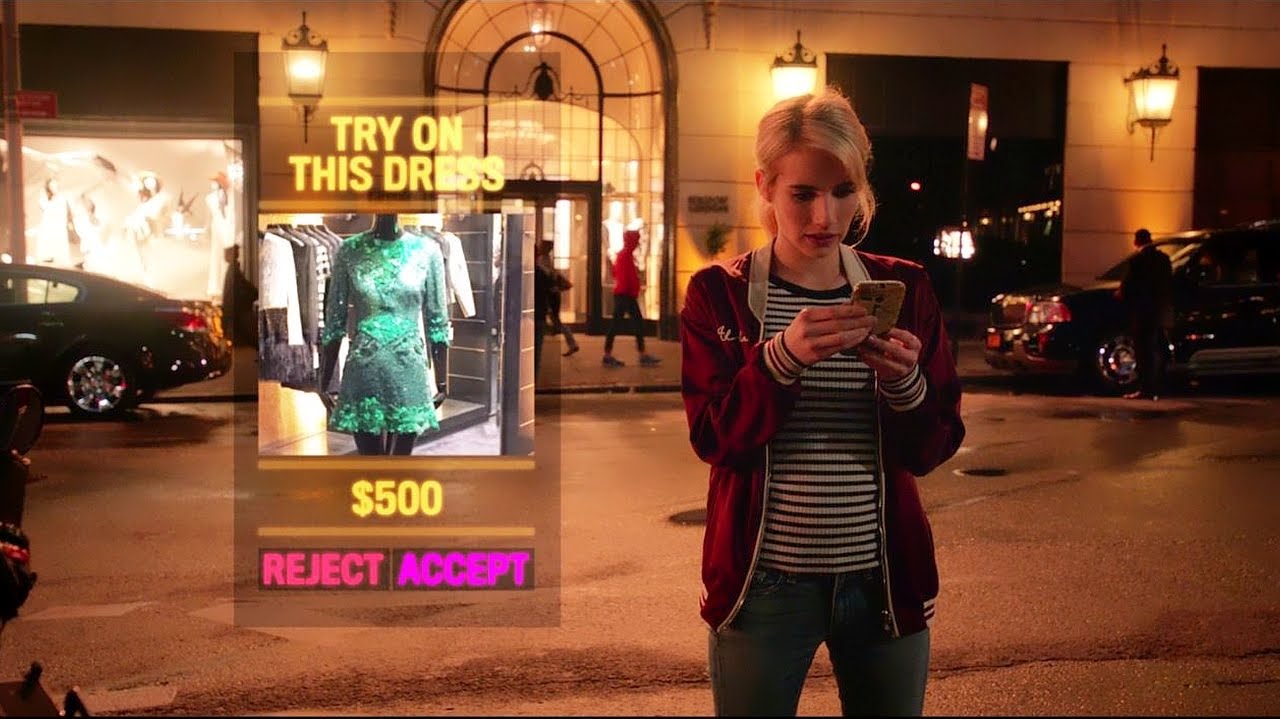

Nerve and Ingrid Goes West mark a fairly radical shift from that construction, though. In Wall Street, the phone is an accoutrement, a capitalist signifier of Gecko’s own power and ubiquity, and those of people like him. In these newer films, the relation is reversed. Our protagonists are creatures of the phone in a way completely alien to a creation like Gecko; the worlds we encounter in Nerve and Ingrid Goes West, the interesting parts of those worlds anyway, largely do not exist outside of the phone. It’s not that the world are fake, as in the “gnostic movies” of 1998/1999 films that Liz has been tackling; it’s that the characters only matter in relation to their technologies, which give shape to the narrative and images.

Nerve and Ingrid Goes West mark a fairly radical shift from that construction, though. In Wall Street, the phone is an accoutrement, a capitalist signifier of Gecko’s own power and ubiquity, and those of people like him. In these newer films, the relation is reversed. Our protagonists are creatures of the phone in a way completely alien to a creation like Gecko; the worlds we encounter in Nerve and Ingrid Goes West, the interesting parts of those worlds anyway, largely do not exist outside of the phone. It’s not that the world are fake, as in the “gnostic movies” of 1998/1999 films that Liz has been tackling; it’s that the characters only matter in relation to their technologies, which give shape to the narrative and images.

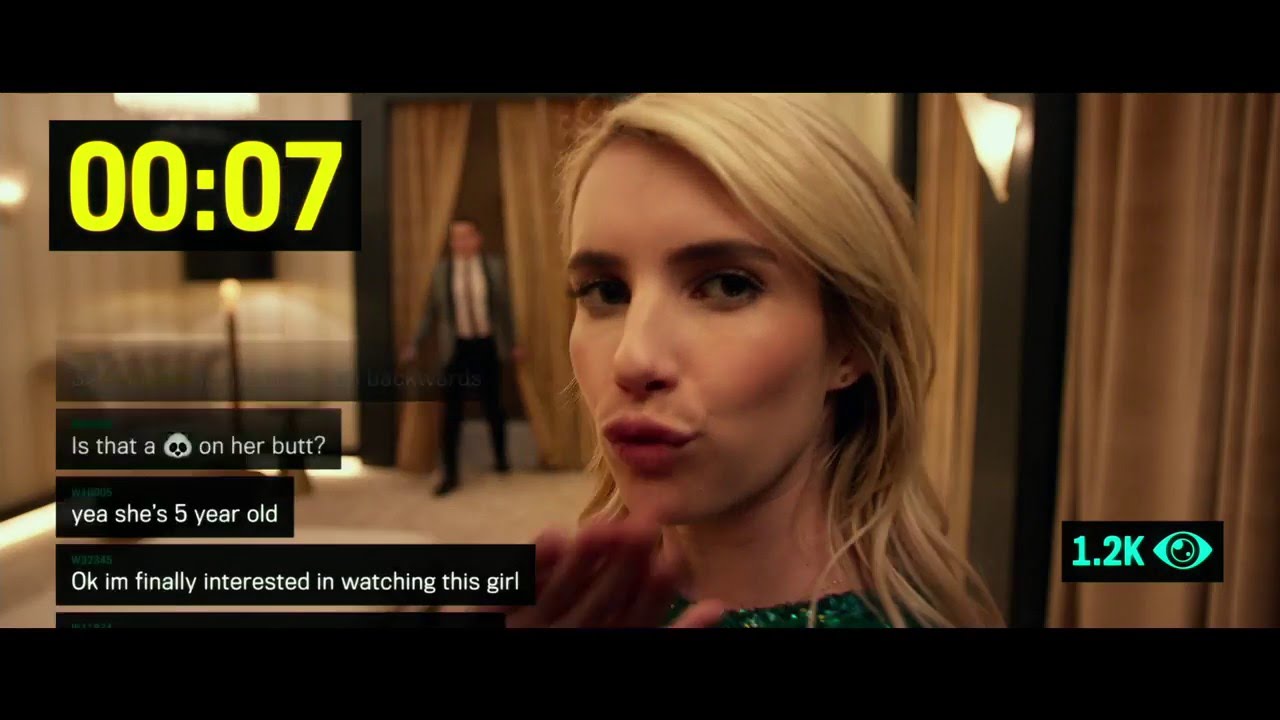

Nerve tells the story of a sort of Dark Web interactive game, in which users sign on as “players” or “watchers”. The watchers suggest outlandish dares, ranging from Jackass-style cringe-comedy to life-threatening stunts, and the players seek to outdo each other for the anonymous approval of strangers (and also prize money). Directors Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman, and cinematographer Michael Simmonds, give Nerve an appropriately videogame pastiche aesthetic, with overlaid text flickering against a garish vision of the world-as-casino; even the diners look like you’re somewhere off-Strip in a YA-friendly Vegas. A once-shy Emma Roberts and a suspiciously casual Dave Franco traverse city streets doing wacky shit, but their real home in the story is somewhere more amorphous and crowd-sourced.

Nerve tells the story of a sort of Dark Web interactive game, in which users sign on as “players” or “watchers”. The watchers suggest outlandish dares, ranging from Jackass-style cringe-comedy to life-threatening stunts, and the players seek to outdo each other for the anonymous approval of strangers (and also prize money). Directors Henry Joost and Ariel Schulman, and cinematographer Michael Simmonds, give Nerve an appropriately videogame pastiche aesthetic, with overlaid text flickering against a garish vision of the world-as-casino; even the diners look like you’re somewhere off-Strip in a YA-friendly Vegas. A once-shy Emma Roberts and a suspiciously casual Dave Franco traverse city streets doing wacky shit, but their real home in the story is somewhere more amorphous and crowd-sourced.

Meanwhile, Ingrid Goes West takes place mostly in a sun-dappled L.A., where Aubrey Plaza’s protagonist, an Aubrey Plaza type, has fled after an unfortunate stint in the mental hospital. She, too, is more an accessory to her phone than the other way around. Consistently refusing to realize that, as David Ehrlich puts it, “No one is as happy as they seem on Instagram, as depressed as they seem on Twitter, or as insufferable as they seem on Facebook,” Plaza’s character constructs her identity through the always-almost obtainable desires of social media. The film’s title, which doubles as her username, hints at a journey of self-discovery and conquest, but in practice it amounts to stalking an Instagram celebrity and remaking herself in that digital image. (Think The King of Comedy by way of The Bling Ring.) Ingrid’s madness is indistinguishable from the technologies that inform it, and the formal trappings that director Matt Spicer rolls out – voiceovers filled with hashtags and awkwardly enunciated emoji descriptions, animated hearts popping out of the image – make sure that no one can fail to notice.

Meanwhile, Ingrid Goes West takes place mostly in a sun-dappled L.A., where Aubrey Plaza’s protagonist, an Aubrey Plaza type, has fled after an unfortunate stint in the mental hospital. She, too, is more an accessory to her phone than the other way around. Consistently refusing to realize that, as David Ehrlich puts it, “No one is as happy as they seem on Instagram, as depressed as they seem on Twitter, or as insufferable as they seem on Facebook,” Plaza’s character constructs her identity through the always-almost obtainable desires of social media. The film’s title, which doubles as her username, hints at a journey of self-discovery and conquest, but in practice it amounts to stalking an Instagram celebrity and remaking herself in that digital image. (Think The King of Comedy by way of The Bling Ring.) Ingrid’s madness is indistinguishable from the technologies that inform it, and the formal trappings that director Matt Spicer rolls out – voiceovers filled with hashtags and awkwardly enunciated emoji descriptions, animated hearts popping out of the image – make sure that no one can fail to notice.

The resolution of these narratives is less interesting than the very fact that they exist. (For the record, Nerve cheats a bit, veering sharply into well-trod conspiratorial vagueness and didactic uplift; Ingrid Goes West has the “courage” of its cynical convictions, and ends on a distinctively unpleasant note.) In both films, the technologies have specific relational functions – Roberts takes these dares to prove herself more adventurous than her friends imagine her; Plaza is presented as a vessel hollowed out by her phone’s expectations but ultimately legitimized in her “realness” by the approbation of strangers. Both are forms of social madness.

There’s something distasteful about all of that, particularly in Ingrid, but something undeniably felt. It’s not simply a question of being alone in a crowd, or falling behind in the aspirational rat-races of presentation, or that our attempts to connect can distance us instead; as in Personal Shopper, where the madness and confusion of grief manifests most acutely in a back-and-forth text exchange, identity itself often hinges on these devices in our cinema right now. The paranoia isn’t really about who is on the other end of the line, or if the call is coming from inside the house. The point is that the house is inside the call.