All movies, of course, come to us pre-packaged in some way, sure. But there is packaging, and there is packaging.

1979’s The Visitor is firmly in the second camp, at least for those of us who see it for the first time now, in hi-def, remastered form and given an aura of the cult secret.

It’s hard to know how I would have taken the movie without the critical paratext (a phrase Gerard Genette uses to denote everything that comes with “the text” but is not “the text” itself). The plot cribs from The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby, and The Omen, but does not mix them together as much as has them all play simultaneously.

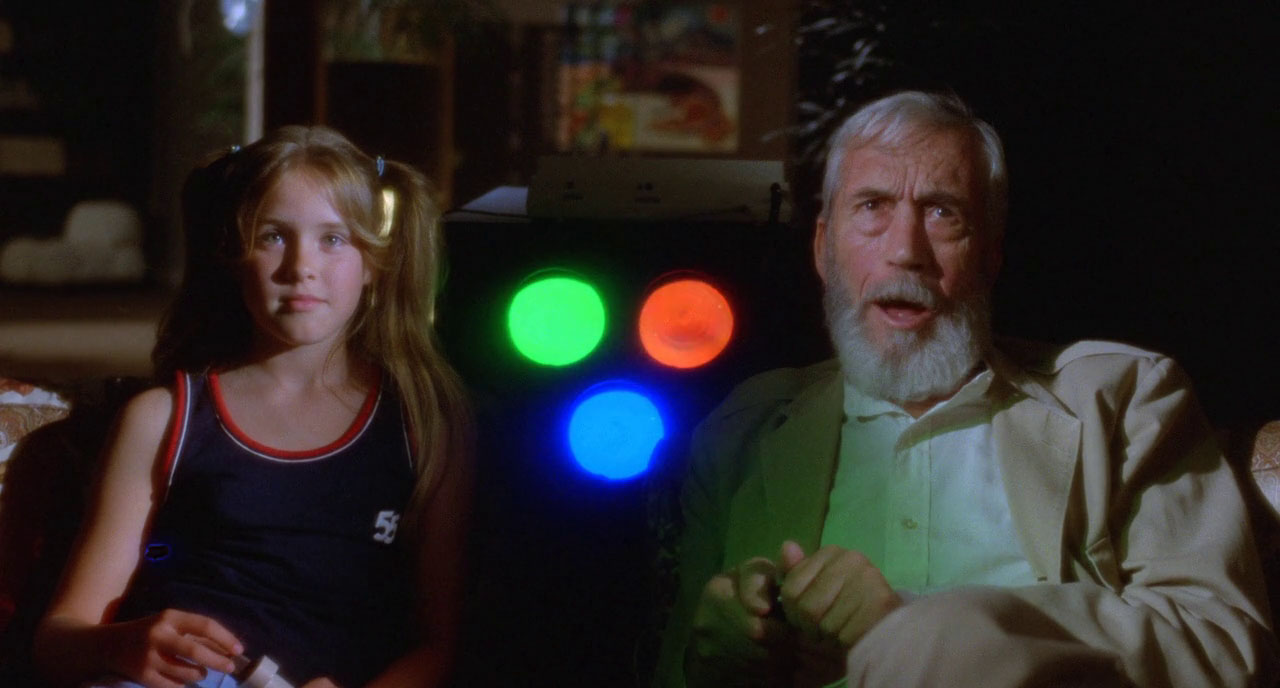

There’s an 8-year-old girl, Katy (Paige Conner), who has loosely-defined developing psychic powers and who is somehow possessed by a demonic force. Her mother, Barbara (Joanne Nail), is being pressured by her boyfriend, who is in league with Satanists, to have another child to further their loosely defined goals.

There’s an 8-year-old girl, Katy (Paige Conner), who has loosely-defined developing psychic powers and who is somehow possessed by a demonic force. Her mother, Barbara (Joanne Nail), is being pressured by her boyfriend, who is in league with Satanists, to have another child to further their loosely defined goals.

All of this is wrapped in a peculiar sci-fi frame as an Obi Wan-esque figure (played by John Huston, bizarrely) comes to Earth to stop the Satanists, whose god is in fact the evil intergalactic fugitive Zatteen (spelling courtesy of Wikipedia). He is hoping to save Katy’s human form so she can hang out with other bald children in the presence of Yahweh, an extremely cult-leader-looking man who seems to live in a spa.

This leaves out a number of subplots that surface for a while and exist mostly to keep the opening and closing credits a little farther apart. Glenn Ford is a detective who seems to be channeling his irritation at being in a bit part directly into his sour and irascible performance, and who dies quickly enough for him to make his tee time. Barbara is paralyzed by a gunshot and ultimately turns to her doctor ex-husband (Sam Peckinpah, again, bizarrely). Shelley Winters somehow manages to make her role as an astrologist maid even more unlikeable than the murderous Satanic child.

This leaves out a number of subplots that surface for a while and exist mostly to keep the opening and closing credits a little farther apart. Glenn Ford is a detective who seems to be channeling his irritation at being in a bit part directly into his sour and irascible performance, and who dies quickly enough for him to make his tee time. Barbara is paralyzed by a gunshot and ultimately turns to her doctor ex-husband (Sam Peckinpah, again, bizarrely). Shelley Winters somehow manages to make her role as an astrologist maid even more unlikeable than the murderous Satanic child.

But no synopsis, no matter how disjointed, can represent the film’s aimless narrative style. From minute to minute, there is almost some sense of coherence, of narrative drive, but suddenly ten minutes have passed and nothing has happened. I counted three clear climaxes, each of which undid the others. Through all of this, the visual style can only be described as “high-budget softcore porn.”

All of this returns me to the opening question: How would we take this film, unadorned by cult apparatus? How would it have been taken if it hadn’t been so hard to track down for so long, if it were available at every Blockbuster? Would it have a mystique still, or would it just be one more wandering, mediocre horror movie?

All of this returns me to the opening question: How would we take this film, unadorned by cult apparatus? How would it have been taken if it hadn’t been so hard to track down for so long, if it were available at every Blockbuster? Would it have a mystique still, or would it just be one more wandering, mediocre horror movie?

That would be a tragedy. The Visitor is a remarkable movie, even though it’s not very good. We should acknowledge the way the paratextual apparatus of the “cult genre film remaster,” just as the paratextual apparatus of the “Criterion Collection remaster,” shape and frame our expectations.

But we should do this not so that we can correct for it, like a warped lens distorting our view. We should instead pay attention so we can choose to apply it more generally, not just when the vicissitudes of the market force it on us. There are a hundred 70s horror movies just as aimless and weird as The Visitor, but that’s no reason to ignore The Visitor – it’s a reason to go out and find them.