Amid all its other signifiers, then and now, 1968 was about youth – its dangerous and liberatory possibilities. Two years earlier, Godard had cheekily announced the arrival of “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola,” but ’68 was their decidedly anarchic coming out party, from Nanterres to Columbia University to Mexico City to the Red Square. The youth uprising was one of many, but it was a through line, on the streets and screens.

In one sense, it had been a long time coming before the open repressions of 1968 put a point on it, making the state indistinguishable from its unremittingly adult brutality and perversity. At the same time, newness itself seemed suddenly new. Richard Neupert, in A History of the French New Wave Cinema, writes:

It is startling to recall that the term ‘teenager’ first entered everyday language in 1945, and it was really the 1950s that saw young people identified as a separate, definable age group falling between childhood and adulthood… While sociologists, psychologists, and community leaders debated the potential social dangers of this new lifestyle, its perceived existence and differences helped fuel a widespread fascination with all things young and new.

The Nouvelle Vague is a notoriously tenuous term – encompassing fashion, politics, modes of production and distribution, location photography, cinejournals, and more – and these days seeming, like pornography, more recognized when seen than rigorously defined. Still, youth was front and center – the films were fast, cheap to produce, full of life, vernacular, and sex.

But for the youth of ’68, raised on the Bardot of … And God Created Woman and denunciations of the French “tradition of quality,” the New Wavers were already a generation gone; no longer young Turks themselves, Chabrol, Godard, and Truffaut were the fathers and honorary guardians of the revolution, even as they sat on the frontlines.

But for the youth of ’68, raised on the Bardot of … And God Created Woman and denunciations of the French “tradition of quality,” the New Wavers were already a generation gone; no longer young Turks themselves, Chabrol, Godard, and Truffaut were the fathers and honorary guardians of the revolution, even as they sat on the frontlines.

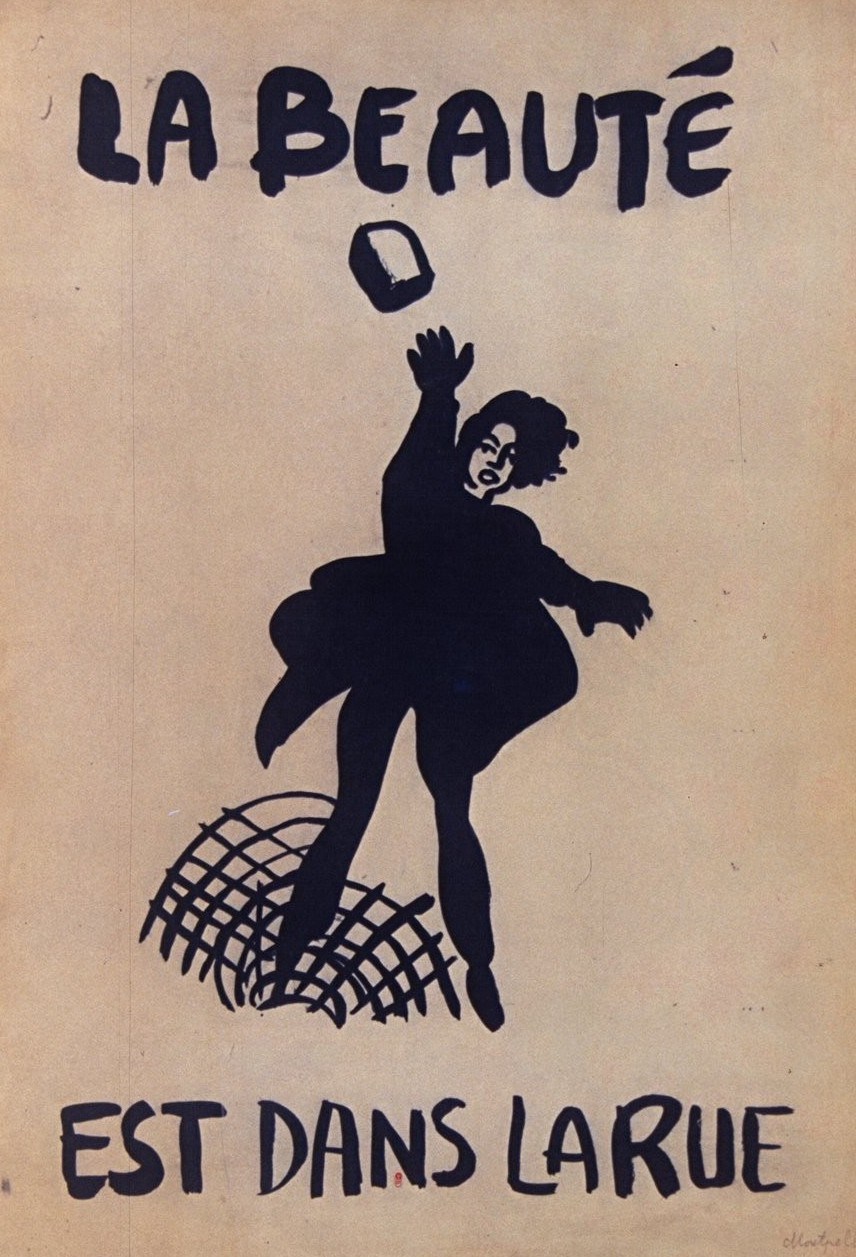

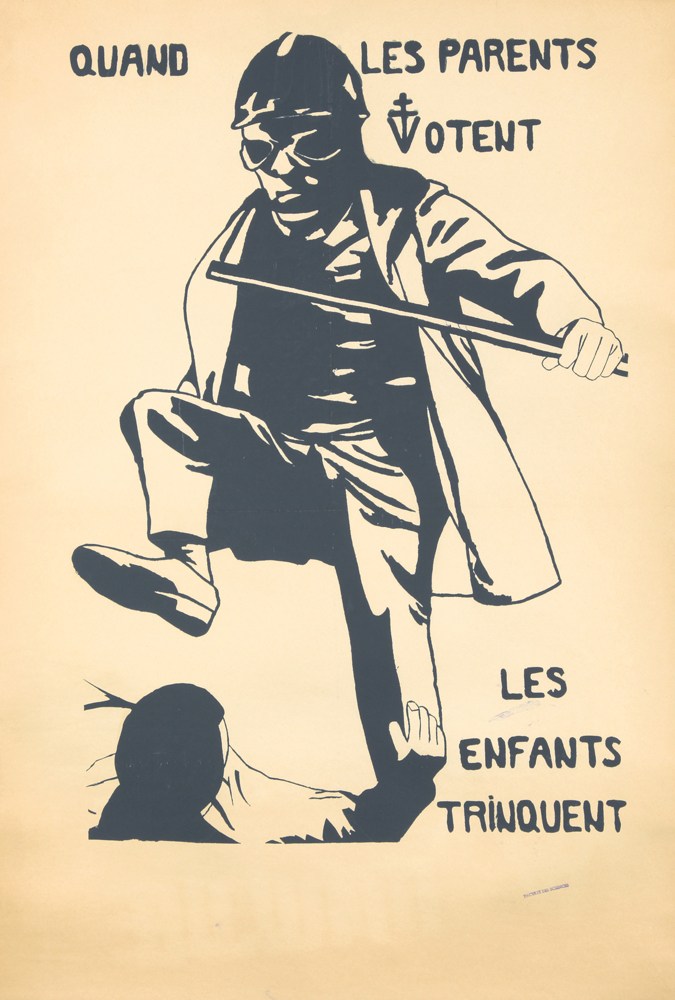

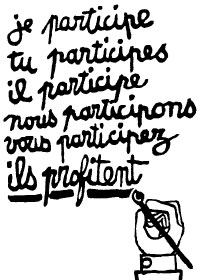

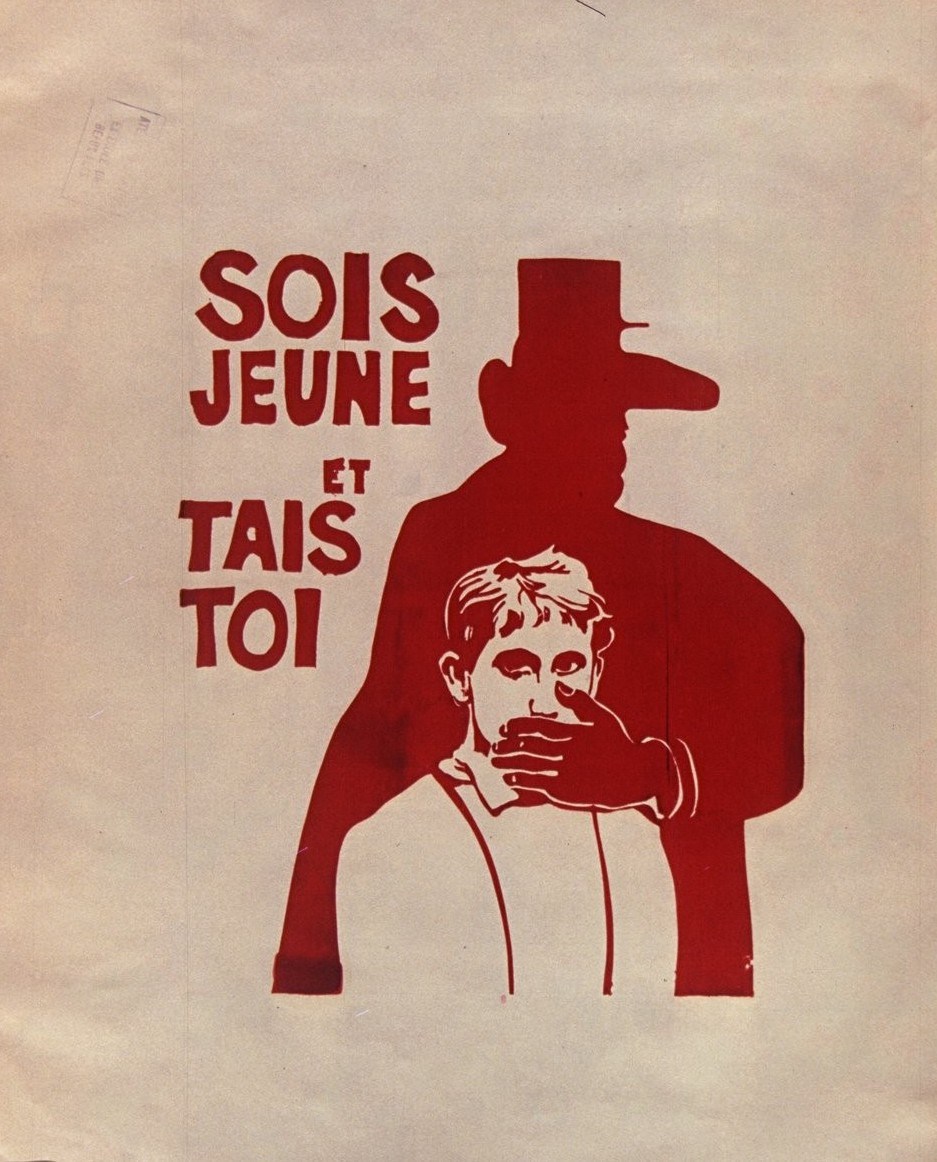

The image of a slightly nerdy Chabrol as interlocutor between protestors and riot cops never fails to amuse, with the kids fighting for “something about Langlois” and the cops bashing heads because they are cops and cops are eternally stupid. The slogans of 1968 – Beauty Is In The Streets; Faster, Comrade, The Old World Is Behind You; Live Without Dead Time; A Single Nonrevolutionary Weekend Is Infinitely More Bloody Than A Month Of Total Revolution – speak of a young man’s game as much as “Never trust anyone over 30” ever did.

In other words, outnumbering adults 5 to 1, the youth of ’68 wanted the world and they wanted it now. It’s perhaps useful to move out of the cobblestone riot streets of Paris to get a perspective on the aesthetic revolutions of that moment. Two films, one American and one from the U.K., can help.

In other words, outnumbering adults 5 to 1, the youth of ’68 wanted the world and they wanted it now. It’s perhaps useful to move out of the cobblestone riot streets of Paris to get a perspective on the aesthetic revolutions of that moment. Two films, one American and one from the U.K., can help.

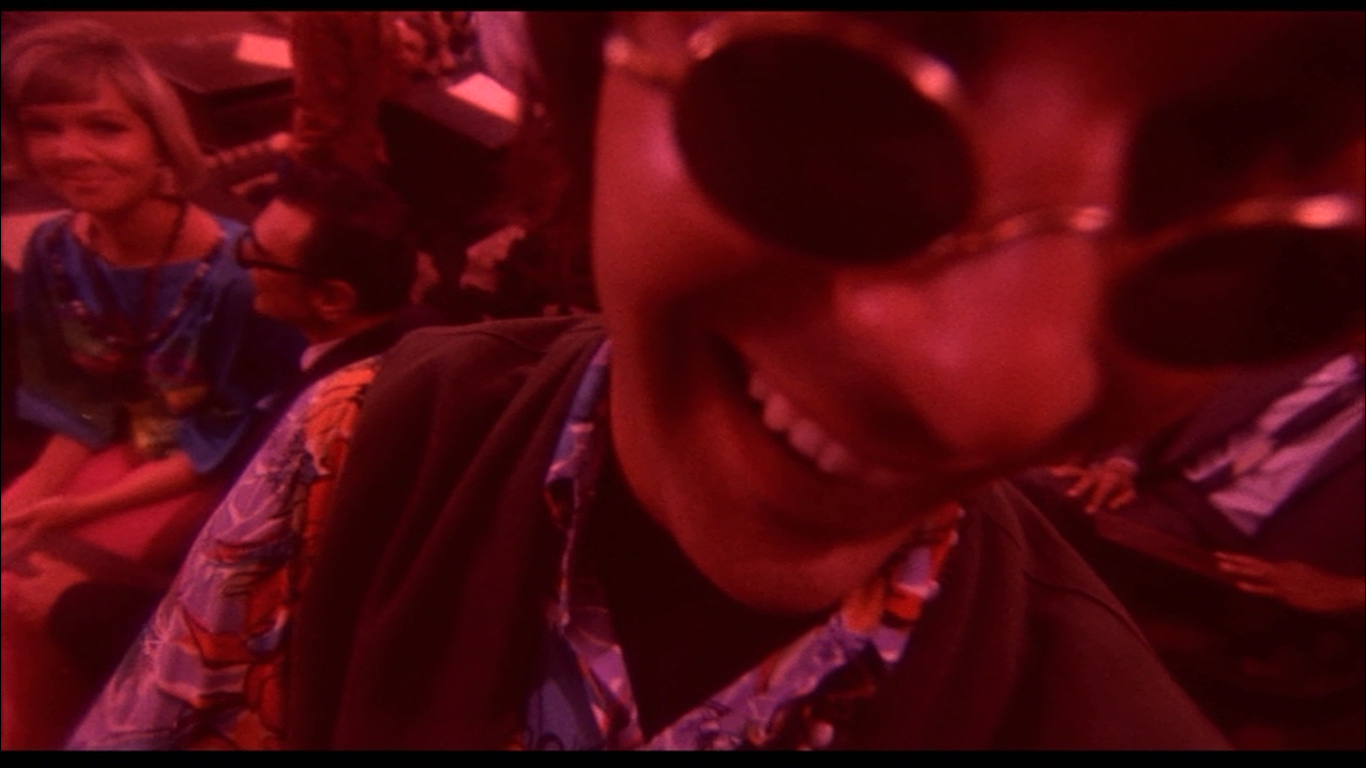

Released in May ’68 proper, Wild In The Streets is the first, and the much sillier. A U.S. drive-in sensation, the 40th top-grossing film of 1968 is the reductio ad adsurdum of never trusting anyone over 30; in its “chilling,” Twilight Zone-aping final moments, it imagines a future where the ceiling for civic participation will be set at 10 years old. It’s an exuberantly cynical text, dressed up in youth culture and dripping with disdain. The kids loved it, as a commenter on Roger Ebert’s bemused review remembers:

In the Summer of 1968, I won tickets to see the movie at the Midtown Theater, Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA for the East Coast Premier, sponsored by radio station WFIL-AM. I still have the original ticket. I invited my girlfriend Caryl, we took the train from the suburbs. Besides meeting the Disc Jockeys, they closed off Chestnut Street and had two go-go dancers suspended in giant birdcages, dancing to Rock music. I liked all the spotlights and sounds – a real happening.

Cool.

Wild In The Streets is about the meteoric rise of Max Frost, who escapes a childhood of suburban drudgery and Freudian overstatement to become the Lizard King-like frontman of a rock outfit. (They sound like Strawberry Alarm Clock — in fact, the fictional Max Frost and the Troopers’ “Shape of Things to Come,” bemoaning the game-changing police massacre that catalyzes the youth rebellion’s escalation, reached #22 on the non-fictional Billboard charts, like some sort of acid rock Spinal Tap — and Richard Pryor plays the drummer. I never said Wild In The Streets made sense, or 1968 for that matter.)

Wild In The Streets is about the meteoric rise of Max Frost, who escapes a childhood of suburban drudgery and Freudian overstatement to become the Lizard King-like frontman of a rock outfit. (They sound like Strawberry Alarm Clock — in fact, the fictional Max Frost and the Troopers’ “Shape of Things to Come,” bemoaning the game-changing police massacre that catalyzes the youth rebellion’s escalation, reached #22 on the non-fictional Billboard charts, like some sort of acid rock Spinal Tap — and Richard Pryor plays the drummer. I never said Wild In The Streets made sense, or 1968 for that matter.)

A politician courting the youth vote (Hal Holbrook, looking lost even before he gets forcibly fed LSD) makes the mistake of enlisting Max’s help; Holbrook’s Vietnam-inflected quest to lower the voting age to 18 is hijacked, with the accelerationist rock star announcing from the stage that it ought to be 14 instead. Les jeunes in the streets of Paris may be comparing reforms to chloroform on the screenprints cascading out of occupied studios and demanding total revolution, but their American counterparts in Wild In The Streets are all about the ballot box.

For a while. After getting Holbrook elected, they campaign for one of their own – the film’s most memorable sequence involves their newly elected spokeswoman, with a three-pointed hat and a tambourine, declaring to Congress that “America’s greatest contribution has been to teach the world that getting old is such a drag.” From there, it’s on to the Frost Presidency and the … re-education camps. Wild In The Streets beat Jello Biafra to this particular joke by a decade, though the “hippie fascists” here really only mean to get the olds out of the way. The rivers are spiked with LSD, the camps don’t feature any possibility of exit, and Hawaii, the only state that resisted Frost’s shamanic charms electorally, is effectively drugged into oblivion.

For a while. After getting Holbrook elected, they campaign for one of their own – the film’s most memorable sequence involves their newly elected spokeswoman, with a three-pointed hat and a tambourine, declaring to Congress that “America’s greatest contribution has been to teach the world that getting old is such a drag.” From there, it’s on to the Frost Presidency and the … re-education camps. Wild In The Streets beat Jello Biafra to this particular joke by a decade, though the “hippie fascists” here really only mean to get the olds out of the way. The rivers are spiked with LSD, the camps don’t feature any possibility of exit, and Hawaii, the only state that resisted Frost’s shamanic charms electorally, is effectively drugged into oblivion.

The rest of the world is only briefly mentioned, in that typically American fashion; we never find out how revolutionaries elsewhere respond to the youth takeover, and the whole freaky endeavor seems a lot more like the following year’s The Stewardesses 3-D than the previous one’s La Chinoise. We do, however, discover a flaw in the system, along with Max; when the newly installed regime leaders scoff at a 9-year-old child questioning their legitimacy, he responds that 24 years old is ancient.

The rest of the world is only briefly mentioned, in that typically American fashion; we never find out how revolutionaries elsewhere respond to the youth takeover, and the whole freaky endeavor seems a lot more like the following year’s The Stewardesses 3-D than the previous one’s La Chinoise. We do, however, discover a flaw in the system, along with Max; when the newly installed regime leaders scoff at a 9-year-old child questioning their legitimacy, he responds that 24 years old is ancient.

The counter-revolutionary attempt at “but dig this!” satire in Wild In The Streets is blindingly stupid, and must have been met with giggles from whatever stoned audience members were still paying attention by the end even at the drive-in. But its not-quite-square anxiety about the direction all this youth tumult is headed seems real enough. In December 1968, a British director would address it with much more skill and nuance.

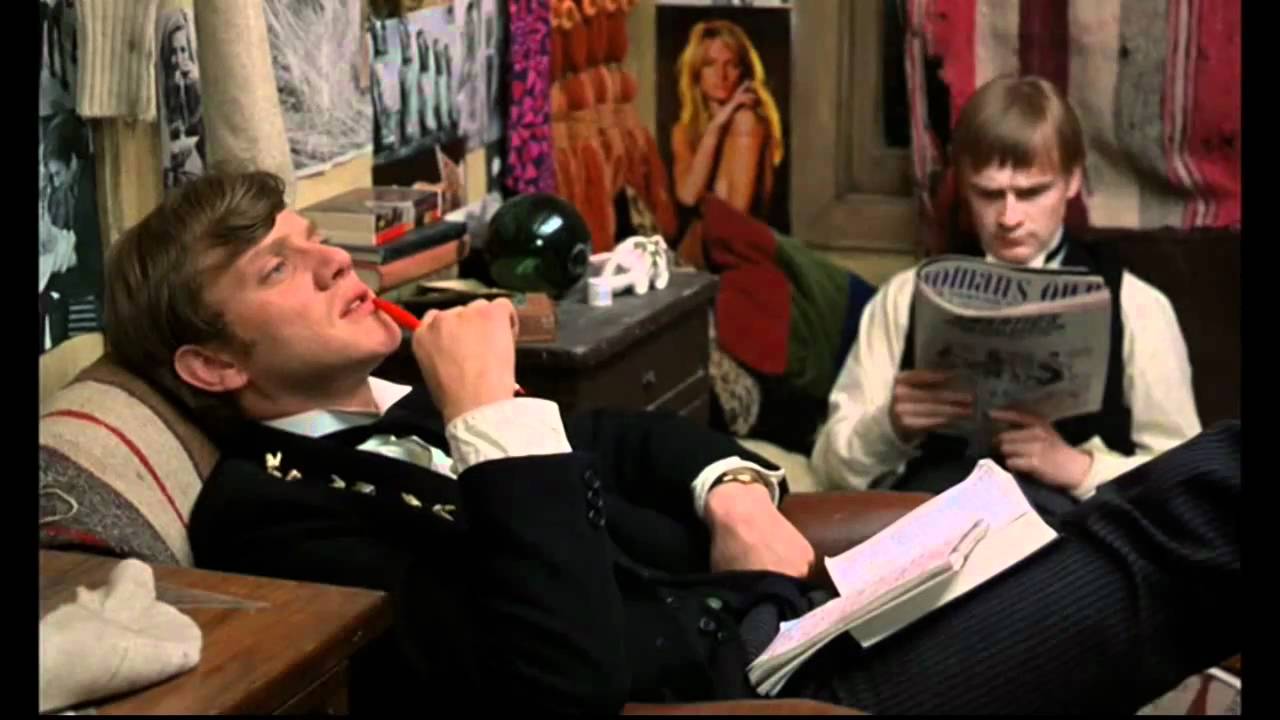

What’s most striking about watching Lindsay Anderson‘s If… today is how little of it, climactic guerilla gunfight notwithstanding, is overtly political — how conventional, even mannered it often seems. In sentiment, though, it has much more in common with the Situationists’ “If we only have enough time…” then the Kipling poem it shares a title with.

What’s most striking about watching Lindsay Anderson‘s If… today is how little of it, climactic guerilla gunfight notwithstanding, is overtly political — how conventional, even mannered it often seems. In sentiment, though, it has much more in common with the Situationists’ “If we only have enough time…” then the Kipling poem it shares a title with.

There are pictures of Che on the prep school walls – some things never go out of style – and Malcolm McDowell‘s Mick Travis enjoys aphoristic proclamations like, “Violence and revolution are the only pure acts,” but its real focus is youth, what it’s like to be young, what it looks and feels like. (Even that proclamation has the ring of youth to it, to say nothing of “When do we get to live? That’s what I want to know,” as David Ehrenstein points out.) The radical shifts between color and black and white – amusingly, a technical accommodation Anderson embraced rather than a piece of aesthetic anarchism or bonus nod to Vigo – give If… a feeling of memory or dream.

At the same time, the gorgeous homoeroticism of its second-most famous sequence points to a space of cinematic desire that is political enough on its own terms, even if it’s not exactly a rock through the cop station window (or, in Wild In The Streets‘ image, a homemade bomb tossed in Dad’s new Chrystler). If… is full of youth’s cries of protest, but they’re fractured and isolated, bouncing off the school’s stone walls.

Power too is fractured, and that’s where Anderson’s anxieties prove most resonant. The face of authority in If… is less the tyrannical schoolmasters – they seem, for the most part, oblivious and irrelevant – than the Whips that serve them like prison guards.

Power too is fractured, and that’s where Anderson’s anxieties prove most resonant. The face of authority in If… is less the tyrannical schoolmasters – they seem, for the most part, oblivious and irrelevant – than the Whips that serve them like prison guards.

The hierarchy of the school is much more realistic and frightening than your run-of-the-mill vision of oppression, because it’s the entitled splinter groups of the young quashing their fellows in anti-solidarity. The enemy is among us, and the revolution is going to be complicated.

If… is a great film, Wild In The Streets is not. But they both share a pessimism about the times that connects them, as 1968 films that both stand somewhat apart from the Langlois Affair and its participants and also share a deep distrust of authority, including the structures of revolutionary leadership. There are no drugs or rock and roll, but quite a bit of sex, in Anderson’s vision; there’s hardly any sex and virtually nothing but drugs and rock n’ roll across the pond. And while neither speaks directly to Vietnam, as Godard decided all films of the time ethically must, you can feel its presence all the same. From the perspective of youth revolution commentary, though, the children of Marx and Coca-Cola have turned out to be anxious insurgents.