It’s awards season, and there’s no shortage of commentary. I might chime in myself in a few weeks. (Spoilers: Boyhood, Ida, The Immigrant, Under The Skin, and Noah would win all the things if it were up to me, and Uma Thurman would get a best Supporting Actress nod for Nymphomaniac Vol 1 — it is not, it turns out, up to me.)

But I thought I’d take the opportunity to highlight some of the best movies I saw this year which won’t be winning awards, primarily because some of them are from nearly 100 years ago.

Without further ado, the best movies of 2014 that didn’t come out in 2014, according to some guy on the internet.

- Sherlock, Jr. 1924

Buster Keaton’s endlessly inventive piece of meta-cinema, in which at one point his classic stone-faced protagonist falls asleep on the job as a projectionist and enters a world of pure film, was easily the biggest revelation of the year for me. I’d seen some Keaton before (though much more Chaplin), and knew enough to expect spirited gags, his hangdog demeanor, and show-stopping stunts (all of which he famously did himself), but I was totally unprepared for Sherlock, Jr.’s frantic bursts of inspiration and genius. I watched it four times in two days. Thank you, staff and readers at the Dissolve.

- Before Sunrise (1995), Before Sunset (2004), and Before Midnight (2013)

The release of Boyhood, and my enthusiasm for it (I know, it’s a lonely road to walk), finally compelled me to face the sad fact that I’d only ever seen the first entry in director Richard Linklater’s “Before” series, an extended character study of two lovers as they meet, meet again, and grow up. I fixed that in short order, and discovered the second two films deserve every bit of their acclaim. In 2014, Boyhood confirmed Linklater as the greatest American poet of time working in movies today, but the Before films demonstrate how expected that should’ve been. I’m still not sure if I’ve recovered from the gut-punch that is Before Midnight, the last and best of the trilogy.

- The Kid with a Bike (2011)

Like Linklater, the Belgian directing duo known as the Dardennes brothers (Jean-Pierre and Luc) have been showered in awards and Oscar-buzz this year, for their film Two Days, One Night. That one hasn’t been released around these parts yet, but their 2011 The Kid With A Bike broke my heart. Its understated but uncompromising approach perfectly suit the story of Cyril, a semi-abandoned, scrappy boy looking for a father-figure. He’s played with a raw urgency by young Thomas Doret, and his adventures around the projects of Liege, Belgium accumulate throughout the film into a portrait of growth and resilience in the economic and emotional margins. And its final scene, which could’ve sank under the weight of its cynicism, instead lands on a moment of grace that was the most quietly beautiful thing I saw all year.

- 3 Women (1977)

Robert Altman claims the outline of 3 Women came to him in a dream. There’s not much on screen that would argue against this. It’s an ethereal, weird film that turns in on itself, much more interested in allusion, symbol, and mood than narrative. Sissy Spacek and Shelley Duvall both turn in monster performances, and, with the possible exception of Under The Skin, I found myself thinking back on this movie more than any other. If Altman wanted to put a dream on the screen, he came close – it’s ravishing, operates according to its own logic, and seems perpetually in danger of being forgotten upon waking.

- MacGruber (2010)

MacGruber is neither ravishing nor ethereal. These are not words one would use to describe Will Forte’s almost staggeringly confrontational SNL spin-off, which holds the incredible title of “worst performing SNL spinoff ever.” For context, this is a group that includes Night At The Roxbury and It’s Pat.

It is, however, the most hilarious movie of 2014, and its 5th best overall, despite coming out 4 years ago! This is a movie where our idiot hero – part MacGuyver, part Bond, all incompetent – deploys the celery trick to distract his enemies. What is the celery trick, you ask? Well, that is Will Forte literally sticking a piece of celery up his ass and chicken-walking around naked, cupping his balls. Classic MacGruber. The men with guns do pause in disbelief, and ask the only plausible question under the circumstances: “What the fuck?” (Not content to let it go at that – a phrase that could basically serve as a tagline – Forte advises his reluctant colleague Ryan Philippe, “You know, it sounds counter-intuitive, but if you ever use the celery trick, you want to focus on the big end. Otherwise, it just falls right out.” Philippe replies: “Yeah, I’m not ever going to use the celery trick.”) This is actually the least gross joke I could reference, so put that in your back pocket. Or just go watch MacGruber, that shit is hilarious.

- Peeping Tom 1960

Michael Powell’s creepfest Peeping Tom effectively ended his otherwise successful career, as critics savaged its lurid plot about a cameraman who films himself killing women with a knife protruding from the camera itself, and then obsessively watches his work in a screening room at home. Audiences stayed away in droves. Thanks to the efforts of his acolyte Martin Scorcese and others, there’s been a recuperation of the film since, and it’s well deserved. All the themes about representation, the Male Gaze, and the controlling power of the image that have dominated horror and suspense movies over the years are present here, and the figure of obsessive madness at its center is compelling. Like Sherlock, Jr., Peeping Tom is a movie about movies, but not everyone wants to be reminded that they too are voyeurs when the images start rolling, especially when the character we are aligned with is a monster.

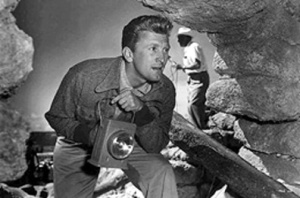

- Ace in the Hole (1951)

For all the lighter, wackier fare for which he’s known, the great Billy Wilder could be a hell of a cynic, and his Ace in the Hole is one of the most acidic satires I’ve ever seen. Kirk Douglas is a journalist seeking to break out from his low-profile gig for a local paper in Albuquerque and hit the big time with a blockbuster story. A worker trapped in a cave-in gives him the opportunity, and he does whatever he can with his purple prose, some occasionally “massaged” details, and eventually intrusion into the whole situation, so the story can keep building. Ace in the Hole is also about representation and the power to shape viewpoints, along with cut-throat capitalism and the lies we tell ourselves to get by. The film proceeds at a slow burn, as hypocrisies increase, and then it explodes.

- Jules and Jim (1962)

Francois Truffaut once wrote “The film of tomorrow will not be directed by civil servants of the camera, but by artists for whom shooting a film constitutes a wonderful and thrilling adventure.” I don’t know if this is how he experienced filming Jules and Jim, but it would be appropriate. The film’s first 15 minutes are a breathless rush of exposition, as we meet these two friends and learn their histories. Eventually, they meet Jeanne Moreau’s Catherine, who has love affairs with both. It’s complicated, but there’s never true animosity between them – both the quiet and manic moments the three share are highlights of the movie, and at one point they even live together in a house (a cute shot shows two of them opening the shutters, the third below, and greeting each other in the morning). It’s a melodrama for sure, but it’s also a wonderfully intimate portrait of a particular kind of triad, placed against the backdrop of war and changing norms, propelled by some sort of furious force of compassionate honesty. I’m embarrassed I hadn’t seen this until now, but I’m glad I did.

- Wadjda (2012)

Haifaa Al Mansour, the first female Saudi Arabian film director to shoot on location in the country, helmed this portrait of razor sharp, free-minded, endlessly adorable Wadjda (Waad Mohammed), a young teen who dreams of nothing more than learning to ride a bike and beating her friend in a race. Mohammed is an instant star, and Al Mansour’s pointed contrasts – Wadjda decides to win a Koran recitation contest, in order to use the prize money to purchase something her teachers consider inappropriate for a girl – and her powerful depictions of homelife, ritual, and day-to-day interactions would be impressive even if you set aside her unique biography as a filmmaker. It’s a really well done piece of Saudi Arabian feminist bike advocacy, with a lead performance that makes you wonder what Mohammed will do next. Basically, stop reading and go see it now, if you haven’t.

10. Persona (1966)

Ingmar Bergman is a huge blind spot for me, so catching up to Persona was gratifying. Like Altman’s 3 Women (a film that draws deep from its well), Persona is dream-like and hard to pin down. Liv Ullman’s Elisabet is a performer who had a breakdown on stage and has refused to talk since. Bibi Anderrsson is Alma, the nurse who takes her to a remote seaside cabin to recuperate, and hopefully bring her out of her shell. Things get pretty weird. Alma fills the house with chatter, compensating (or over-compensating) for Elisabet’s silence – she reveals secrets, dreams, desires. It seems she can’t stop talking, and the nurse/patient role seems to flip. The characters begin to take on each other’s aspects, and things get increasingly tense. And then Bergman blows your mind.

![9c Ingmar Bergman persona3_thumb[3]](https://ludditerobot.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/9c-Ingmar-Bergman-persona3_thumb3-300x203.jpg)