It’s October. There’s a crispness to the autumn air, the falling leaves crunching underfoot, the smell of the first fires of the year issuing from neighborhood hearths as Halloween approaches, bringing with it all of the ghouls, goblins, and other horror figures that emerge from the shadows of the season.

Commentary

Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window is a true classic, beloved by cinephiles, critics, theorists, and casual moviegoers alike. Masterfully layered, featuring some of the best work its illustrious cast ever turned in, and providing analytical fodder for countless analyses of its themes and artistry, Rear Window unquestionably earns its place in the pantheon of masterpieces.

Recently, the good folks at Swampflix invited me onto their podcast to talk about the films of Richard Kelly: Donnie Darko, Southland Tales, and The Box. (I’m leaving aside Domino, because he did not direct it, and because it is both atypical, a Tony Scott film, and also bad.)

The zombie occupies a unique position in the cultural imagination. Neither living nor dead, neither human nor animal, it is a boundary-blurring figure.

It can be, and usually is, frightening in its monstrosity and lack of category cohesion, but it can be tragic, too: most zombie stories involve the shock and sadness of seeing loved ones become … not quite themselves.

One of the fascinating revelations gleaned from the Silent Era is the degree to which there really is nothing new under the sun. As Martin Scorsese told Roger Ebert, “Each film is interlocked with so many other films. You can’t get away.

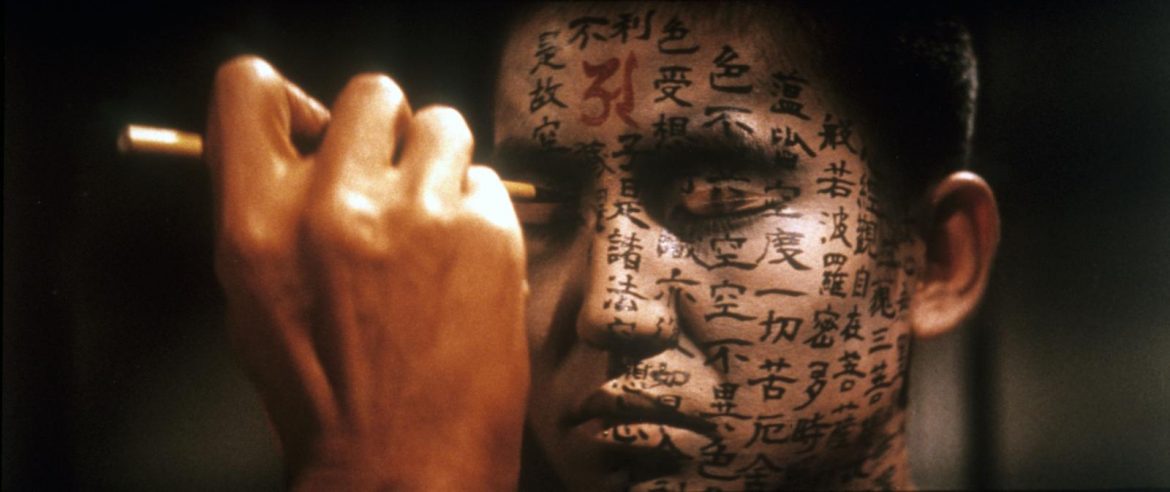

Things are not quite what they appear to be in Surname Viet Given Name Nam, Trinh T. Minh-ha’s masterful 1989 documentary.

Beginning as an apparently straightforward portrait of several women’s lives in past and present Vietnam, the film grows increasingly experimental as it continues, morphing into a feminist, post-colonial interrogation of form, positionality, the authority of the image, and film ethnography itself.

Winner of the 2015 Golden Lion in Venice, Lorenzo Vigas’ From Afar (Desde allá) is the slowest of slow burns. A story of distance, proximity, and perspective, it teases out the hidden meanings behind character surfaces in ways that either prove thrilling or excruciating, depending on your tolerance for long stretches of silence and similar arthouse trappings.

In an online film community of which we are both members, my pal Liz Lerner suggested a novel and fascinating idea. For the entire month of September, we are watching and considering films from a specific, arbitrarily chosen year, attempting to locate their concerns, aesthetics, and quirks in the material conditions of their creation and examining what they might have to say to each other.

Happy Labor Day!

You know, the day in early September that Grover Cleveland declared a federal holiday as a halfhearted apology for his troops murdering several workers during the Pullman Strike in 1894, a desperate, election-year attempt to stave off radical reform while also conveniently distancing the U.S.

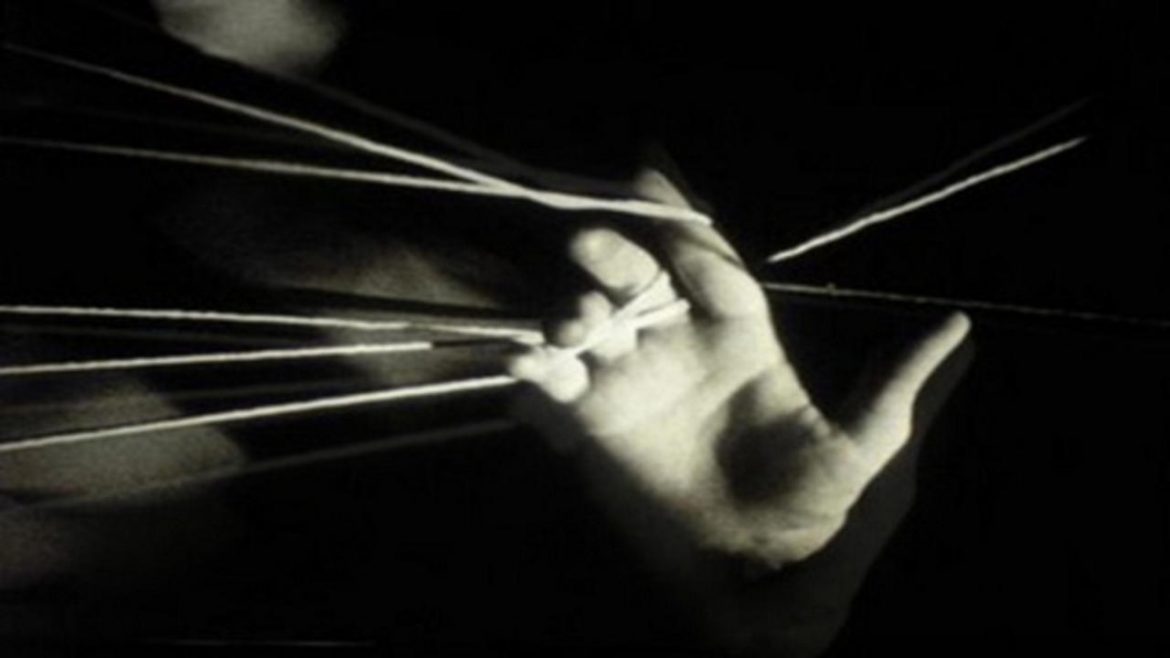

The works of Maya Deren are hugely influential touchstones for experimental cinema, frequently cited and studied. Her luminous debut Meshes of the Afternoon, covered here as part of the Counter-Programming The Great Movies series, is a widely recognized classic of the form, a dreamlike visual interrogation that, in Deren’s words, “externalizes an inner world to the point where it is confounded with the external world.”