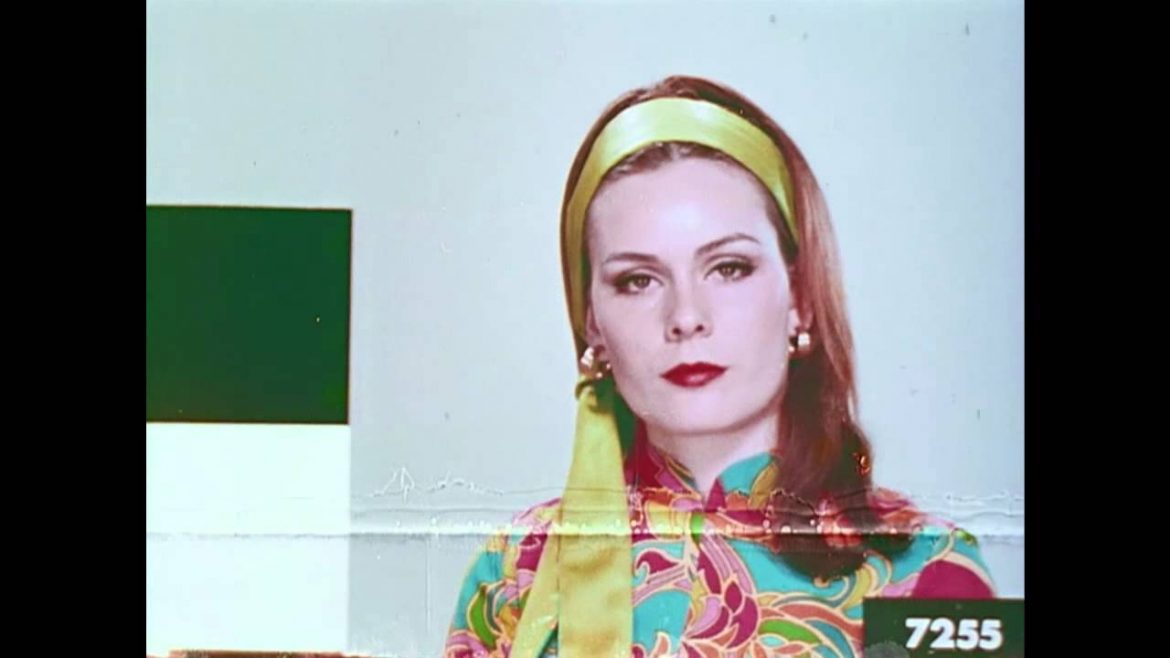

Like many people in the post-cinema age, I suspect, I first encountered them in the closing sequence of Quentin Tarantino‘s Death Proof: Leader Ladies – or Shirley Cards, or in the off-puttingly Orientalist language by which they’re more traditionally known, China Girls.

Film

1. Lost Noise and Found Sound

– Sounds of the projector box (h/t Sam): “These recordings, made in 2016 and 2017, document the shifting sonic texture of the cinema projection box, as it changes from 35mm to digital projection.”

– Noise collections: “After realizing that I was using the wrong sounds, I got to work trying to find the right ones.

Cinema, according to Nicolas Winding Refn, is “generally not an art form anymore.” Too extreme, or not extreme enough? It is “dead … [and] clings on to our feet as we move forward.”

Film’s physicality is one aspect of Refn’s gleeful proclamations of doom.

In a world of near-constant commercial imperatives, the library’s very existence is something of a miracle. It’s easy to forget just how rare it is to simply exist in a space where you aren’t expected to purchase something until you’re standing in one.

Bluray was meant for the grand, beautiful classics of the film world: your Lawrences of Arabia, your Two Thousands One. But it has also done a service to a different, much less distinguished kind of film. It has recovered the shocking ugliness of films like Two-Minute Warning.

There’s a near-consensus among critics that 2018 was an unusually strong year for film, and I can’t disagree. My list for the year is heavily tilted to the 4-star and above, even with some glaring gaps in the mix – I missed BlacKKKlansman, for instance; I’m waiting to see Roma screened at the Castro in 70 mm, like the cinephile tool I am; I didn’t see the new Claire Denis, or the new Andrew Bujalski, or the new Hang Sang-soo, or the new Frederick Wiseman.

Josephine Decker‘s work carries with it a high-wire sense of danger, an aesthetic of possibility and collapse. Whether in the costumed genre trappings of Thou Wast Mild and Lovely, the shifting and uneasy ambivalence of Butter on the Latch‘s just-this-side-of-horror stay at a Balkan folk gathering, or (especially) the self-immolation of Flames, in which Decker’s camera focused with supreme discomfort on her own relationship, the viewer is simultaneously at a remove and much, much too close, piecing together fragments with a mounting sense that the whole edifice could topple.

When we talk about “chosen families,” we usually mean close-knit circles which, through our agency in their construction, stand as more authentic than the biological ones we were born into. They might be safe havens from the abusive homes to which fate has assigned us, but even when they’re not, the simple act of selecting them grants them a different, truer status.

“The world is a mystery to me,” the awkward, aspiring writer Lee Jong-su tells his new “Gatsby-like” acquaintance Ben, at a moment of a maximum queasiness in Chang-dong Lee‘s Burning. The film is a mystery to us, not just in its genre mechanics but in terms of how we are supposed to engage with it: Burning talks and moves like a mystery, lingering on images in ways we’ve been trained to recognize as meaningful, before trailing away like smoke.

One of the many wonderful things about my friendship with Rick Kelley is that, despite being two contrarian film nerds, and despite one of us being a queer woman living in rural Indiana and the other one being a straight guy living in Berkeley, we actually end up with pretty similar opinions on a lot of things.