A group of older Zambian women — seated on the ground, penned in by a fence, faces painted and contorted into shrieks, bodies gesticulating wildly, long fluttering ribbons attached to their native dress like leashes — are photographed by smiling white tourists.

rick

Lake Volta, formed when the massive Akosombo Dam was completed in 1965, covers nearly 4% of Ghana. With a surface area over 3,000 square miles (that’s 13 Lake Meads!), it’s one of the biggest man-made lakes in the world and, as photographed in Alyssa Fedele and Zachary Fink‘s compelling documentary The Rescue List, surely one of the most beautiful.

We are familiar with the “making-of” documentary, but Sandi Tan‘s Shirkers turns it inside out. This is a “losing-of” documentary — a relentlessly charming love letter to indie cinema and its irrepressible DIY spirit, but also a confounding psychological mystery that asks, “How do you represent a film that exists almost entirely in memory?”

There’s a distinct lack of fury at the heart of Desiree Akhavan‘s The Miseducation of Cameron Post. This is worth noting, since the “gay conversion therapy” boarding school on which it focuses offers plenty to be furious about. But in adapting Emily M.

One of cinema’s great ironies is that, for all the talk of representation and making the hidden visible, much of its power comes from withholding instead. Certainly this is true of slow cinema, of that poetic tendency which, in his landmark 1972 treatise, Paul Schrader called “the transcendental style in film.”

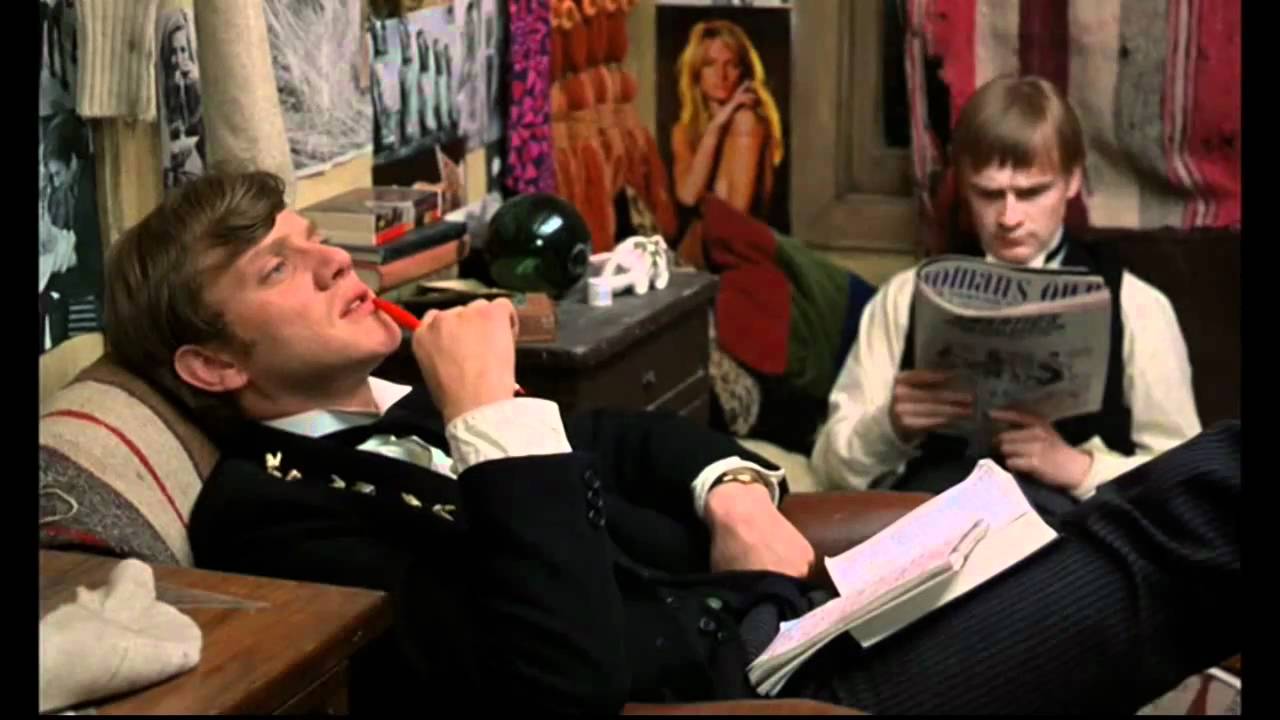

Boredom is Counterrevolutionary: The 1968 Youth Revolts of If… and Wild In The Streets

Amid all its other signifiers, then and now, 1968 was about youth – its dangerous and liberatory possibilities. Two years earlier, Godard had cheekily announced the arrival of “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola,” but ’68 was their decidedly anarchic coming out party, from Nanterres to Columbia University to Mexico City to the Red Square.

With the 50th anniversary of May ’68 – and the famed “events” thereof – approaching, it was a good time to come across the vital documentary Henri Langlois: Phantom of the Cinematheque at my local library. Jacques Richard‘s seven-years-in-the-making account of the father of film preservation only briefly touches on those events, and has its eyes too fixed to the screen to contextualize them rigorously in the larger social upheaval of that year, but it’s scope feels right all the same.

Welcome to Fan Service, a new, typically sporadic (#onbrand) feature in which I feed the hungry beasts / wonderful humans of Patreon by focusing on a subject of their choice. (As with most things, this is borrowed from Nathan Rabin, though in fairness, for all his accomplishments, I’m not sure he can technically claim to have invented “taking requests.”)

Arriving to overblown fanfare and unreasonable expectations, Ava DuVernay‘s A Wrinkle In Time was never going to live up to the hype.

It was bad enough that box office watchers openly wondered how A Wrinkle In Time would compete with Black Panther, a money-printing machine of historic, multi-hyphenate proportions.

For most revered mid-century filmmakers, noting that a particular film featured their first original screenplay and was their first in color would seem to guarantee it additional attention. Curiously, that’s not really the case for Satyajit Ray‘s Kanchenjungha (1962). A careful tapestry of small interactions set against a backdrop of physical grandeur and social change, it seems to get lost in the critical shuffle, functioning as a kind of way station between the narrative sweep of the first two entries in the Apu trilogy and the more refined, self-aware craftsmanship of The Big City and beyond.