When I joked on social media that The Fugitive is a movie about how easily middle-aged white dudes can get into and out of buildings, my friends mostly laughed. Perhaps because it was presented as a declarative statement, it seems a bit reductive. Unfortunately for everyone, I absolutely think this is a big part of the film’s enduring appeal. It’s a story about ghostliness, with a pulp noir narrative drawn from both real life, old films, and dreams.

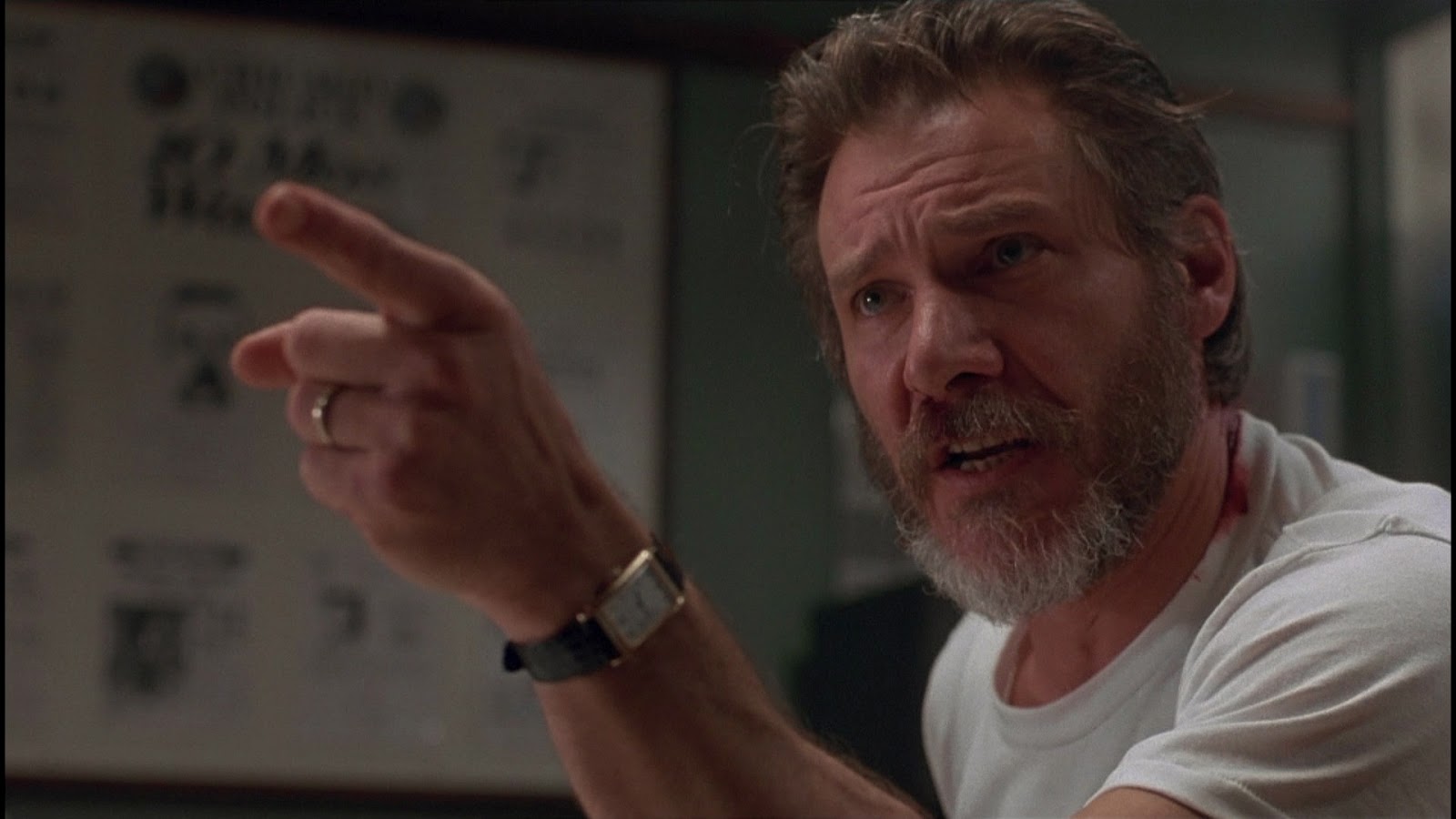

As “Dr. Richard Kimble” (the prestige prefix is non-optional), Harrison Ford brings his shaggy mumble-charm to a cypher of a character. The falsely accused doctor is a prototype of the man with a certain set of skills, and like late-period Liam Neeson, he is on a pulp mission in The Fugitive. Intercut episodes involving saving children’s lives and so forth serve to bolster his credentials and underline both his prowess and his reluctant morality.

As “Dr. Richard Kimble” (the prestige prefix is non-optional), Harrison Ford brings his shaggy mumble-charm to a cypher of a character. The falsely accused doctor is a prototype of the man with a certain set of skills, and like late-period Liam Neeson, he is on a pulp mission in The Fugitive. Intercut episodes involving saving children’s lives and so forth serve to bolster his credentials and underline both his prowess and his reluctant morality.

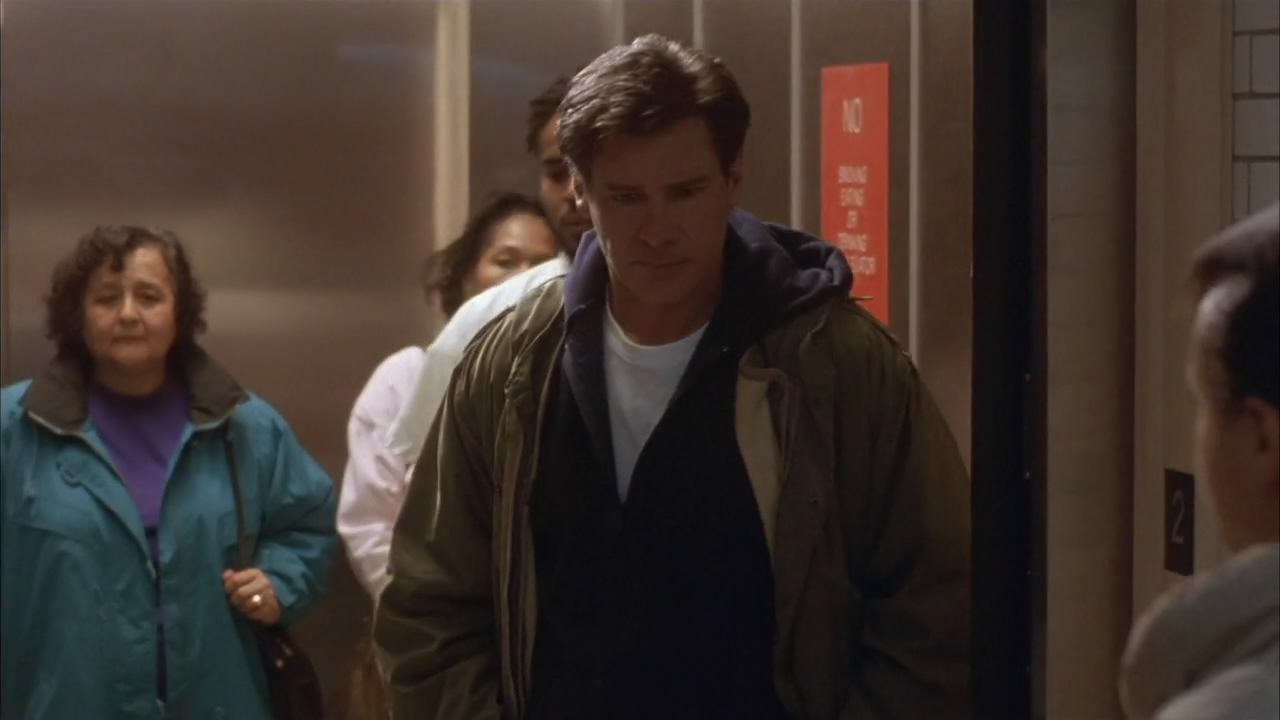

But, for the most part, he serves as a ghost in The Fugitive‘s machine. That machine is mostly constructed from the built environment: dams, hospitals, hotel conference rooms. Much of the film’s excitement — and it is very exciting — comes from this. “How is he going to get out of this one?” is one of the oldest tropes we have; The Fugitive both amps it up and interiorizes it.

Dr. Richard Kimble is on the run from more than Tommy Lee Jones‘ “Deputy Marshall Samuel Gerard.” (The film insists on repetitions of titles for both characters.) Ford’s primary skill is blending in, and then ghosting. It’s how he survives. Perfectly cast, with his hangdog affect and handsome blankness, Ford is everyone and no one, the kind of guy who can just put on a hat and join a St. Patrick’s Day parade. The Fugitive ought to strain credulity with these moves; for some reason, it doesn’t. (Except for when he outright tells a cop that he fits the description of the fugitive he’s seeking, and then they both laugh because his fly is down. Dudes, am I right?)

Dr. Richard Kimble is on the run from more than Tommy Lee Jones‘ “Deputy Marshall Samuel Gerard.” (The film insists on repetitions of titles for both characters.) Ford’s primary skill is blending in, and then ghosting. It’s how he survives. Perfectly cast, with his hangdog affect and handsome blankness, Ford is everyone and no one, the kind of guy who can just put on a hat and join a St. Patrick’s Day parade. The Fugitive ought to strain credulity with these moves; for some reason, it doesn’t. (Except for when he outright tells a cop that he fits the description of the fugitive he’s seeking, and then they both laugh because his fly is down. Dudes, am I right?)

Years ago, a white, male friend of mine was surprised to discover that not just anyone can enter a hotel they are not staying in to use the bathroom. He was like, “I don’t get it, there are bathrooms everywhere.” Indeed there are, for some of us. Like Dr. Richard Kimble, I have simply walked into government buildings, nodded, mumbled something about a meeting, and kept walking. Barring any overt physical distinction — no punk rock t-shirt, no wacky haircut, no holes in my clothes — it’s always worked.

It’s facile to simply point out that white maleness is the standard against which we are judged. We all know that. The Fugitive is clever in its deployment of this fact.

As in The Shawshank Redemption, another enormously popular film released the following year, starring another certain-set-of-skills-having blank slate of a protagonist, white maleness provides cover. We could just call it privilege, and it is, but it seems something more complicated. For instance, in The Fugitive, Dr. Richard Kimble also seems to assume the identity of the buildings he enters (and successfully exits, shedding metaphorical skin along the way). If, since the Expressionists, buildings reflect us back onto ourselves, perhaps one of the characteristics of this variety of whiteness is the way in which we give the building itself shape. If architectural horror is a thing, then so is architectural banality, hiding in plain sight.

As in The Shawshank Redemption, another enormously popular film released the following year, starring another certain-set-of-skills-having blank slate of a protagonist, white maleness provides cover. We could just call it privilege, and it is, but it seems something more complicated. For instance, in The Fugitive, Dr. Richard Kimble also seems to assume the identity of the buildings he enters (and successfully exits, shedding metaphorical skin along the way). If, since the Expressionists, buildings reflect us back onto ourselves, perhaps one of the characteristics of this variety of whiteness is the way in which we give the building itself shape. If architectural horror is a thing, then so is architectural banality, hiding in plain sight.

None of this is to suggest that The Fugitive, in its interrogation of white maleness, is somehow a white supremacist text itself; it’s not. It’s a terrifically enjoyable escape valve of a film, the kind of throwback I am certain my dad would’ve enjoyed. (Perhaps he did; it never came up, though Shawshank was and remains a family favorite.) We marvel at the protagonist’s cleverness, even when the film doesn’t entirely sell it, because we also want the innocent guy to go free, and we want someone to stick it to the man. The swirling conspiracy about falsified liver toxicity reports is profoundly beside the point, so much so that when it arrives, even with its attendant anti-capitalist resonances, we may as well be talking about Unknown‘s corn. It’s a bit of a letdown, frankly.

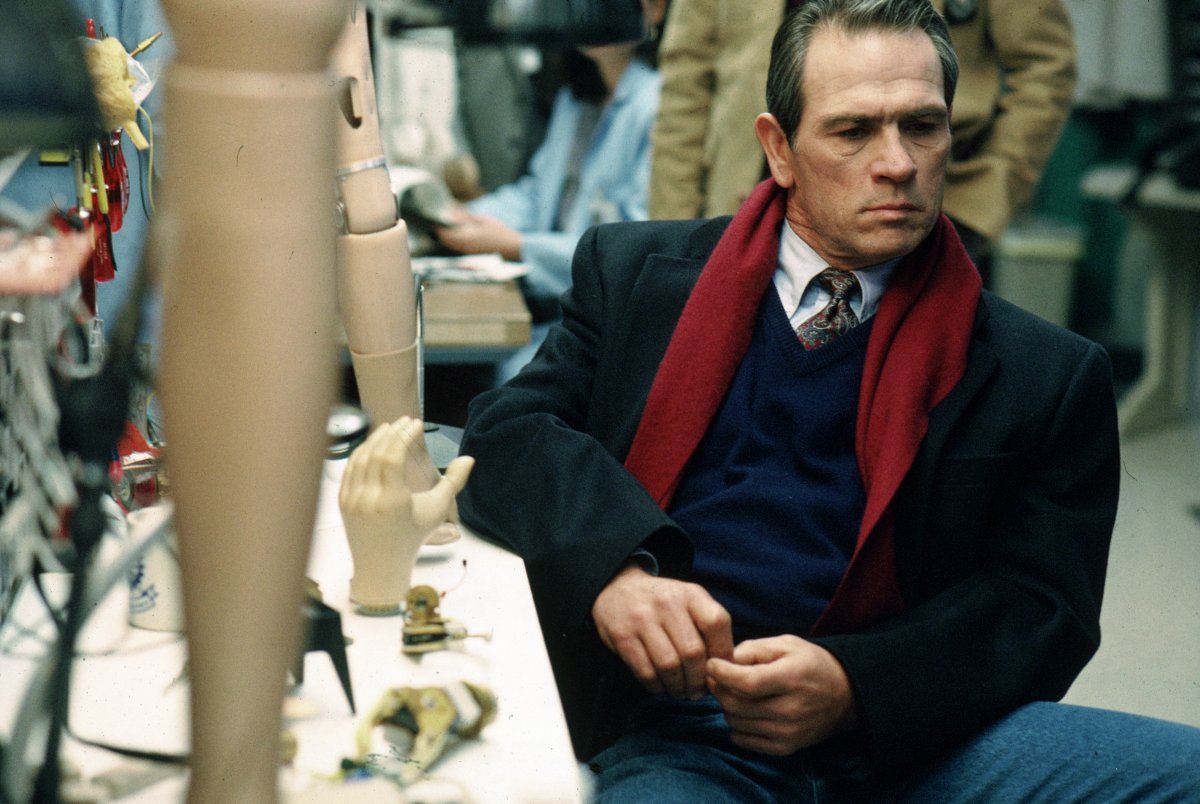

The entire structure of the film revolves around the (rather brutal, rather pointless) murder of Kimble’s wife Helen (Sela Ward), told almost exclusively in flashback. She’s the obvious ghost, but it’s Kimble as ghost who retains our attention and sympathy. We are profoundly more interested in the consequences of her death for him than we ever really are about her death, particularly when, as The Fugitive progresses, Tommy Lee Jones’ dawning awareness of his innocence sets up something like a romance between the two male characters. She is eclipsed, featured only in fragmented, Lynchian nightmares. Her absence at the center of the film mirrors any number of other absences from fields of view.

The entire structure of the film revolves around the (rather brutal, rather pointless) murder of Kimble’s wife Helen (Sela Ward), told almost exclusively in flashback. She’s the obvious ghost, but it’s Kimble as ghost who retains our attention and sympathy. We are profoundly more interested in the consequences of her death for him than we ever really are about her death, particularly when, as The Fugitive progresses, Tommy Lee Jones’ dawning awareness of his innocence sets up something like a romance between the two male characters. She is eclipsed, featured only in fragmented, Lynchian nightmares. Her absence at the center of the film mirrors any number of other absences from fields of view.

The ghostly prosthetic limbs which The Fugitive loves dwelling on also bolster this idea of partiality, of incompleteness. Something is always missing. It’s enough to give Derrida a headache.

Still, it’s that nexus of freedom and claustrophobia, endless possibility for exciting transformation and endless bounding of choices, which provide The Fugitive‘s anxious energy. Dr. Richard Kimble may or may not be in the building, but something sure is.