I remember, very distinctly, when I regained a delight in writing about movies. It was around January 2016, and I was in a pretty miserable place. I had left a college I liked for a number of reasons, among them because I was giving up on my film studies plans. It had been so thrilling at first, getting a couple of chapters published and getting to present at conferences. It took me a while to realize that, frankly, there were no jobs, and that the bar to publication was a lot lower than it seems.

So I had given up and returned to a college I hated, just because it was the shortest path between me and my long, long delayed bachelor’s degree. (Finally graduating on Friday, only eight years after I left high school!) When I gave up on the possibility of a practical career in academic film studies, I also gave up on a certain ideal that had been slipping for a while, an ideal I never quite had and that never quite fit in with the rest of what I believed—a belief in the demystifying value of film studies.

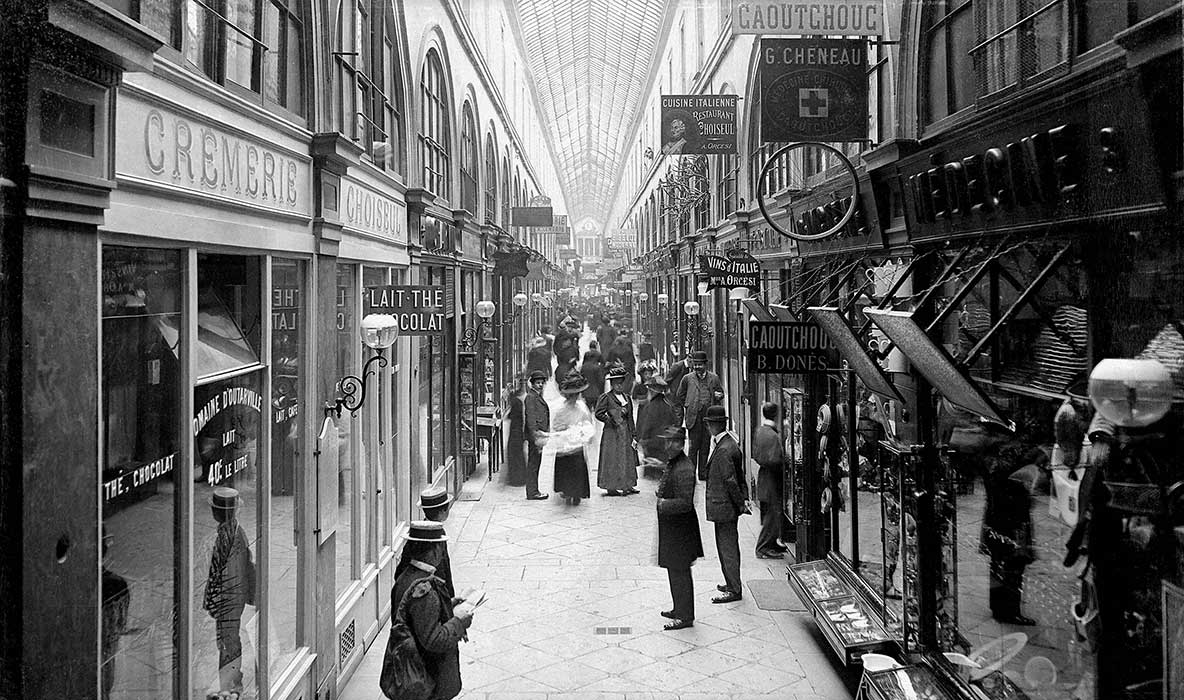

That ideal, that lies dormant in a lot of film studies even now, was expressed by Theodor Adorno in his letter denying Walter Benjamin funding for his Arcades project. He had judged Benjamin’s project—which, in its exploration of popular culture and the popular world, didn’t fall into the Frankfurt School’s belief in the slow, careful demolishing of capitalist culture—to be “located at the cross-roads between magic and positivism. This place is bewitched. Only theory can break the spell.”

That ideal, that lies dormant in a lot of film studies even now, was expressed by Theodor Adorno in his letter denying Walter Benjamin funding for his Arcades project. He had judged Benjamin’s project—which, in its exploration of popular culture and the popular world, didn’t fall into the Frankfurt School’s belief in the slow, careful demolishing of capitalist culture—to be “located at the cross-roads between magic and positivism. This place is bewitched. Only theory can break the spell.”

That’s what we all seemed to want to do: to break a spell. I was at heart a Lacanian. It was, funnily enough, not Zizek, but Todd McGowan’s The Impossible David Lynch that converted me to that curious cult. It featured a clear-cut set of concepts that could be applied to basically any traditional narrative. It really felt like it could break spells. It could turn every theater into Burrough’s naked lunch: “a frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.”

I still think Lacanian film studies is a fascinating field, much more interesting than just Zizek. It wasn’t the type of writing I was doing that was letting me down, and it wasn’t that despite all of the spell-breaking everyone I was reading was doing nothing in the world seemed to change. It was something more general.

It was, I now realize, a problem with the entire vampiric structure of that kind of writing. That kind of film studies writing takes the pleasure of an audience and attempts to explain it like an alien. It can be “duped” pleasure, false pleasure, like what Adorno and the Frankfurt School was looking for, like the psychoanalytic schools and Marxist schools dissected, or “un-duped” pleasure, sincere pleasure, which we see more in the formalist, “scientific” schools of Bordwell and his Post-Theoryians.

It was, I now realize, a problem with the entire vampiric structure of that kind of writing. That kind of film studies writing takes the pleasure of an audience and attempts to explain it like an alien. It can be “duped” pleasure, false pleasure, like what Adorno and the Frankfurt School was looking for, like the psychoanalytic schools and Marxist schools dissected, or “un-duped” pleasure, sincere pleasure, which we see more in the formalist, “scientific” schools of Bordwell and his Post-Theoryians.

The point is that none of this writing can explain the pleasure of writing and reading about movies itself. Academics and traditional film critics both have their explanations for this. For academics, the explicit pressure is the slow progress of objective knowledge, and the implicit pressure is the academic structure—publish or perish, as they say. Film critics are writing about their own pleasure (or lack of pleasure), and are writing so that you, in the future, can increase yours, by watching something enjoyable or avoiding something painful.

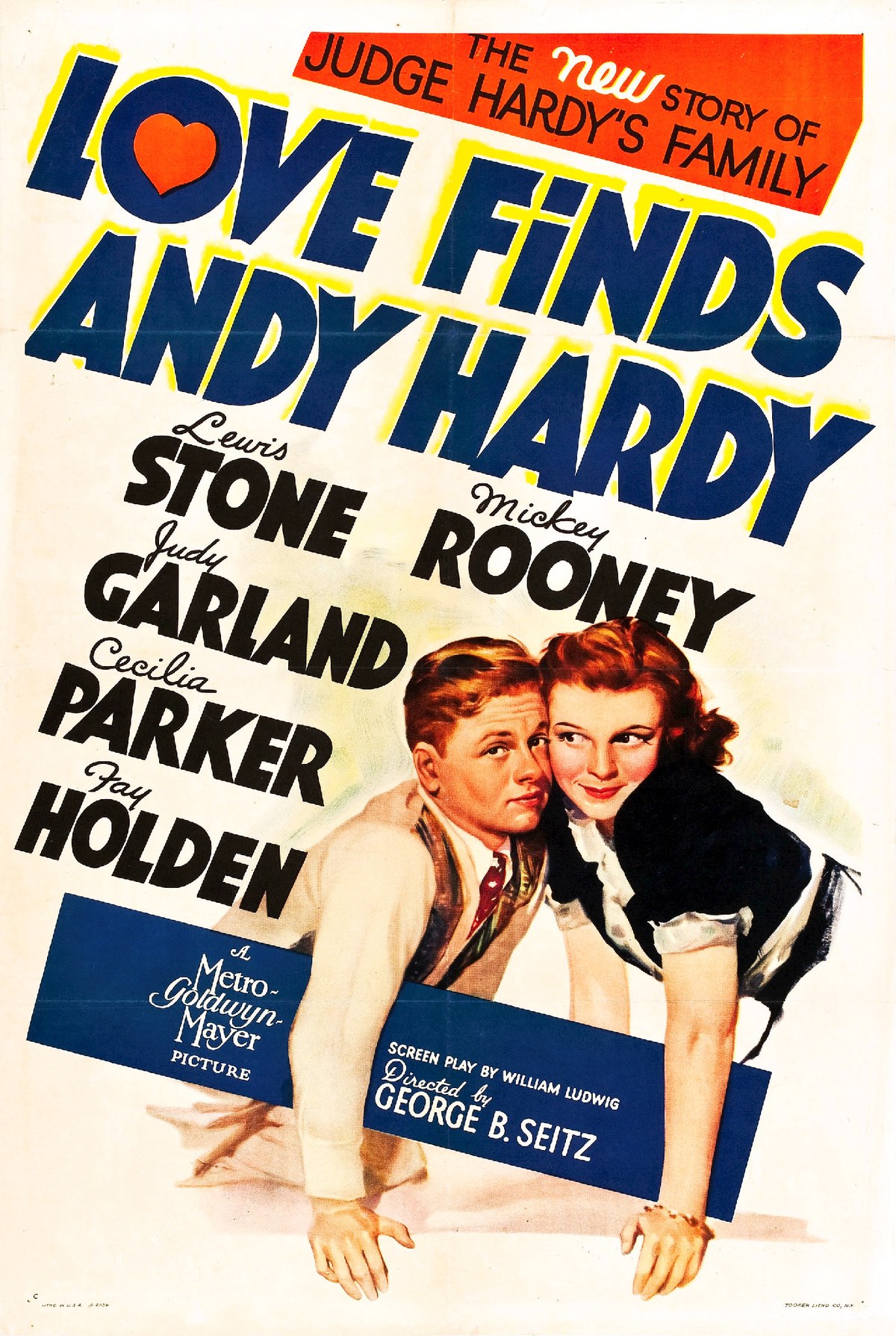

But whether it’s academic or popular-level, the paradigm of film writing, the ends it seems to be aiming for, have nothing to do with giving you a reason to enjoy reading it. Which is why I had given up on it, until I was wandering through our library’s PN section (that’s film, in Library of Congress) and randomly grabbed a book by Robert Ray: The Avant-Garde Finds Andy Hardy.

Ray’s book is mainly focused on using a variety of oddball techniques to analyze the Andy Hardy movies, an enormously popular series of films in its day that gets practically no serious attention these days. He borrows a few techniques from Roland Barthes, but most of them are his own invention (apparently, along with his grad students, who he is careful to cite—something tragically rare in academic writing). But more than the tricks, it’s the style in which he is writing, and his goals in writing. He’s writing to write writing that’s fun to read.

Ray’s book is mainly focused on using a variety of oddball techniques to analyze the Andy Hardy movies, an enormously popular series of films in its day that gets practically no serious attention these days. He borrows a few techniques from Roland Barthes, but most of them are his own invention (apparently, along with his grad students, who he is careful to cite—something tragically rare in academic writing). But more than the tricks, it’s the style in which he is writing, and his goals in writing. He’s writing to write writing that’s fun to read.

That’s my favorite thing about Ray, and it crosses all his books. (The ABCs of Classical Hollywood is tremendously fun.) Pleasure and mystery ooze from the pages. It revitalized me, like Dougie sticking a fork in an electrical socket.

To this day, that’s been my goal: to write writing that’s fun to read.

—

There are two reasons I am talking about all of this here. For the last month, I’ve been putting together two pieces a week for this site, and I began to wonder how well I was communicating my goal here. Rick is super well-versed in critical theory (probably more so than me, honestly), but he tends to reference it less in his articles on here. I, on the other hand, can’t get through a piece about Alien: Covenant without referencing Kierkegaard.

Too often when writing about anything in the humanities—film, literature, theater, or anything else—writers (but academics in particular) bring up thinkers from other fields, but mostly philosophy, and apply those thinkers to the text in question, as if they can clarify the film/book/play under discussion. I think that’s a bad way to think about film criticism.

I don’t think other writers—Marx, Lacan, or anyone else—can be brought in to “demystify” a film. I tend to think of philosophy like Gilles Deleuze did: a particular kind of literature, with concepts filling in for characters. (Perhaps like a very odd kind of mystery novel, where other writers can respond to the detective, “No, that’s not how it happened, and I can prove it.”)

When philosophers write about art, they are usually writing about a concept they created called art. They’re not revealing some kind of substrate level. (Again, to use Deleuze: the reason he took so long to be popular in film studies was because people kept using his books Cinema 1 and 2 [PDFs], which are explicitly books about the philosophical concept of film, not books about film.)

The only reason I bring up philosophers when talking about movies is because it’s fun. It’s fun to try to work out connections between adjacent fields like philosophy and art. It’s fun to see how the systems line up, how there are certain things in the relationships between objects in and around a movie that are similar to relationships between concepts.

So when I’m connecting some writer to a movie, don’t think I’m trying to, to use Adorno’s term, demystify anything. The only thing I’m trying to do is write things that are fun to write and fun to read (because writing is, really, just a form of reading.)

—

The other thing regards a bit of a rut into which I’ve gotten myself. When you’re looking at an upcoming week—“oh, gotta get pieces in by Monday and Wednesday”—it’s easy to plan simply to watch one new movie, then write 600 words about it or whatever. That works wonderfully for a lot of people, but it doesn’t really work for me.

I’m a compulsive re-watcher (as well as re-reader, re-listener, re-everything-er). And usually when re-watching something, I end up connecting it in different ways. A piece is more an impression of a particular viewing than anything else.

Academics don’t like to write about movies more than once. You write your David Lynch book and move on to the next guy, and so on. The implicit narrative of academia is that when you’re writing about something you’re extracting something from the movie. You’re using the tool of some author to get down to its core and drawing it out. But I’m not working that way, so I don’t see any reason to do it.

In other words, I treat this space as much as a journal, a workspace, as anything else. I’m planning in the coming weeks to write about a number of contemporaneous films about realizing your world is “fake”—The Matrix, eXistenZ, The Thirteenth Floor, Dark City, and The Truman Show, all from 1998/1999. But the articles that come out of that mini-project are going to be more an attempt to work through a theory than to present one. In other words, the writing is as much a process of discovery as one of explanation.

In other words, I treat this space as much as a journal, a workspace, as anything else. I’m planning in the coming weeks to write about a number of contemporaneous films about realizing your world is “fake”—The Matrix, eXistenZ, The Thirteenth Floor, Dark City, and The Truman Show, all from 1998/1999. But the articles that come out of that mini-project are going to be more an attempt to work through a theory than to present one. In other words, the writing is as much a process of discovery as one of explanation.

So it’s useful to think of these pieces more as a workbook than a review. No piece has the final word on a movie. There could always be more, if there’s a good excuse.

—

Hopefully all of this methodology hasn’t been too boring for anyone, particularly those without an academic background. It just seemed useful to explore why I write for Luddite Robot. I haven’t mentioned Rick in any of this, mostly just because I didn’t feel comfortable speaking for him.

I guess really, my hope is this: that this was pleasurable to read.