Last year, I took part in the Scary Time Festival of Fright and Terror known as Spooktober, and watched 31 horror movies over the course of the month. It was fun!

I had every intention of doing so again this year — I even have a list; a weird list, sure, but a list nonetheless, with relevant criteria filled and everything — but I’ve fallen way behind. It’s increasingly unlikely I’ll hit that target, though I suppose I could give up some of my more time-wasting exercises, like sleeping, and make it happen. I guess we’ll see.

In the meantime, I have managed more than a few. Here are an initial five, with more to follow. As in the past, my hope was to focus on new watches — I imagine favorites like The Thing or Night of the Living Dead of The Happening will find their way on to the Spooktober menu eventually, and I’m fairly sure I’ve said enough about The Texas Chain Saw Massacre at this point — but these titles were new to me.

Anthologies are, by definition, a mixed bag. Some are more mixed than others. The ABCs of Death does boast an entrancing entry from Hélène Cattet/Bruno Forzani (whose The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears I very much enjoyed, and whose Amer is on this year’s list), and a few others make an impact. (“D is for Dogfight” is particularly good, and “X is for XXL” has a very brutal point to make). But this was, is, and shall remain the movie about magic farts.

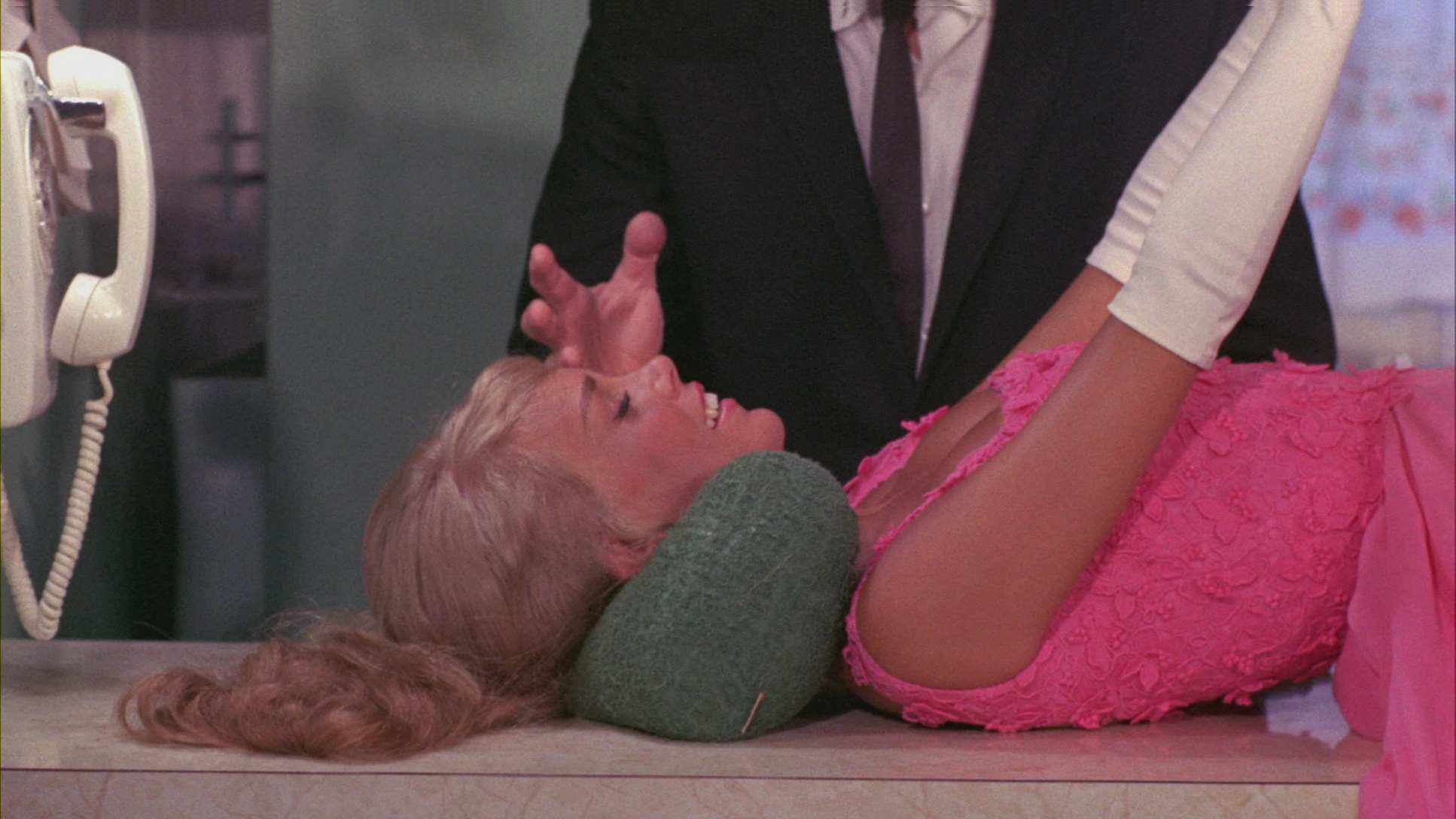

Boasting the twin honorifics “First Splatter Film” and also “Kind of Terrible”, Herschell Gordon Lewis‘ groundbreaking foray into blood, gore, and guts was reportedly born of his disappointment with Psycho‘s timidity.

So instead of Hitchcock’s narrative complexity and implication, we get an Egyptian guy with an inscrutable limp who brutally decapitates women in order to make a magic soup that will summon the Goddess Ishtar. He is tracked by the world’s worst policemen, and their squadron of two other guys who occasionally show up. It all culminates in the world’s worst dinner party, as you would expect.

There’s a lot of fun to be had here with the transparently low budget, and Blood Feast is a genre essential. But you get what pay for, even at the discount Spooktober rate. I hear later Gordon Lewis marks an improvement, though that’s a pretty low bear to clear in this case.

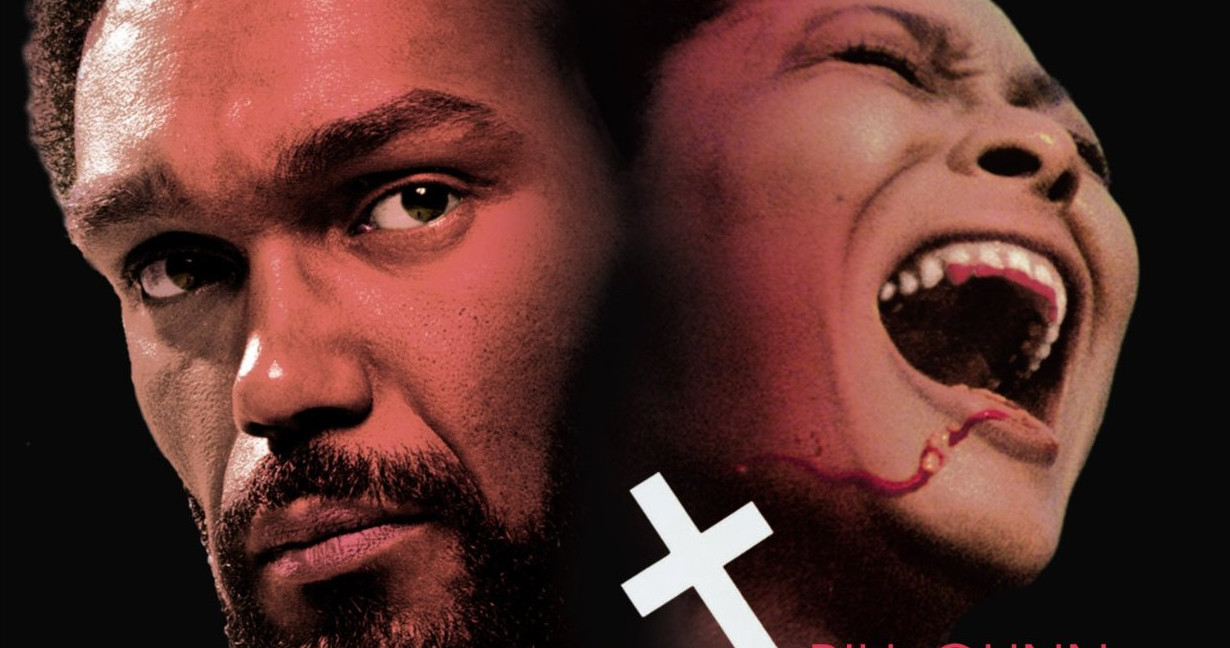

Bill Gunn’s lurid, poetic experiment in form and experimentation bombed upon its release (despite a welcome reception at Cannes), and was radically recut by the distributor into a form disavowed by everyone involved. The French, as it turns out, were right the first time around, and Kino Lorber’s restoration shows why.

Mixing ancient anxieties of tradition and assimilation, meditations on the role of blood in Black Christianity and the street addictions he saw all around him, immersed in stark class divisions and predation on the lower strata, filled with either long silences, a laconic jazz-inflected score, and meandering discursive conversations that never seem to go anywhere in particular … this is heady stuff for a film that was intended, by its financiers, to be a seat-filling Blacula knock-off. The fact that Gunn even had the gall to assemble this particular vision rather than turn in the assignment remains fairly incredible.

Erotic, disturbing, and impossible to categorize, Ganja & Hess would’ve been hailed as a breakthrough if Antonioni had made it (or even Romero, whose Martin it sometimes vaguely resembles, in a mirror-image sort of way). Instead, it stabbed and bled its way into the counter-canon as one of the hallmarks of American Black cinema, steeped, dreamily, in the specific and the mythic at once.

I did not care for Gerald’s Game. I’m very sorry.

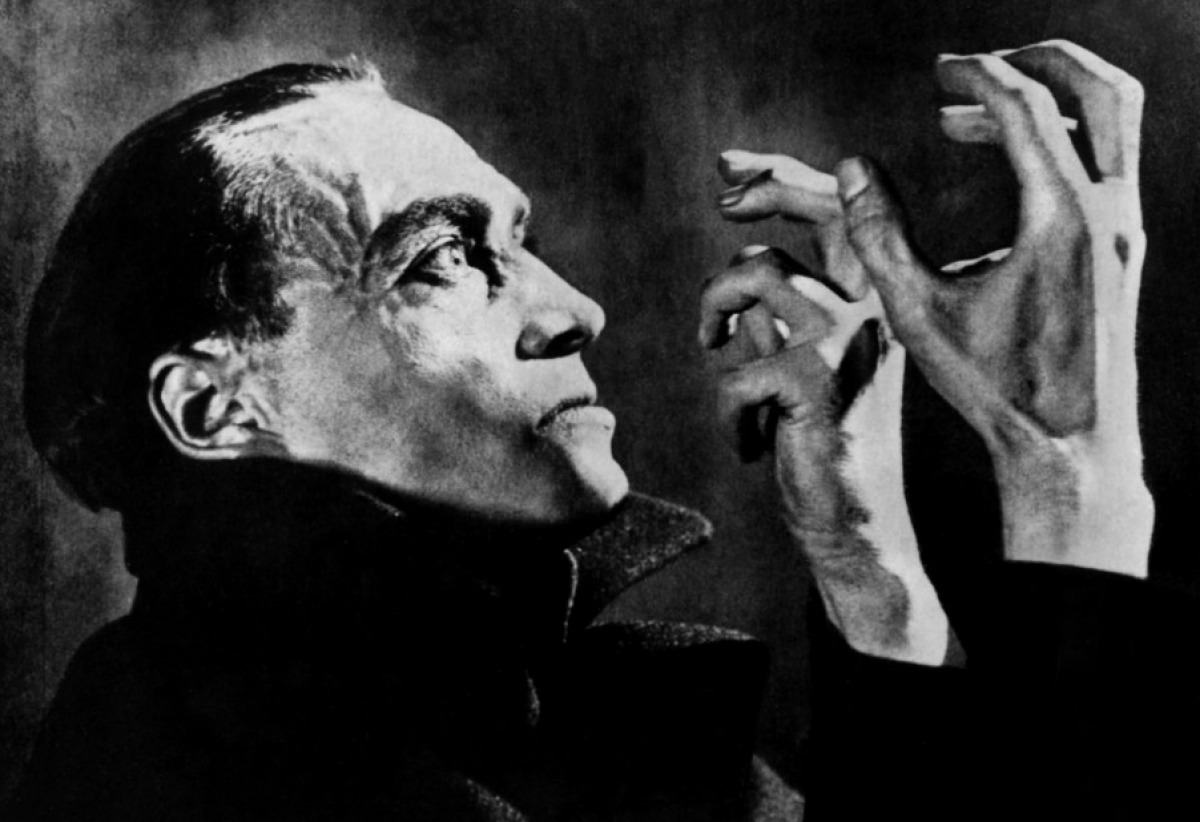

Four years after Caligari, Robert Wiene directed this retelling of Maurice Renard’s story about a successful pianist named Orlac who loses his hands, only to find them surgically replaced with the hands … of a murderer! Like some sort of proto-Ash, or the guy with the idle hands in Idle Hands, this doesn’t turn out well for Orlac and his poor wife. Conrad Veidt is wonderful in the lead, and there are some effective sequences, but the film drags, particularly when the narrative turns to the couple seeking additional income to supplement the money they’ve lost, thanks to his no-good hands, which are way more interested in killing people than playing the piano, and the final resolution ranks among the dumbest in the silents.

Still, it’s scary when your hands turn against you. That’s just a Spooktober fact.