For tonight’s matinee, we showcase three films exploiting what might be called Architectural Horror, which is a term I just made up right now and immediately decided to copyright so please don’t use it or I will have to talk to the lawyers. There’s an inherent link between the built environment of a film’s depiction and its mood, narrative, and meanings, but sometimes the associations are inextricable.

On the one hand, you have The Shining; on the other, The Happening, in which a case could be made that the entirety of its inexplicable running time is constructed out of visits to different buildings and houses, all fraught resonances that M. Night Shymalan apparently found very important.

It’s less a trope than a basic fact, from Expressionism on: the literal architecture of the film impacts, and occasionally embodies, the architecture of the mind it aims to evoke, successfully or not. Here are three successes, separated by decades but linked by a particular fixation on the built environment and its horrific consequences.

1) The Fall of the House of Usher – Jean Epstein (1928)

Poe’s classic bit of Gothic Horror isn’t necessarily terrifying; more filed under, “Steeped in Dread.” In Epstein’s hands, it became on opportunity to deploy every in-camera trick he could conceive, and immersing it all in an appropriately ethereal built environment: a haunted house, a living grave, an unreliable narrator, the tension between what is seen and what is felt, rampant doublings of character, and more.

Somewhere between Impressionism and Surrealism — Usher was the first film screened at the Cinémathèque Française founded by Langlois and Georges Franju, and was championed by Buñuel, who would later dismiss it and Epstein himself as hopelessly bourgeouis — it’s a marvel to look at. Visions of masculine control and post-Freudian hijinks animate it (there’s more than a whiff of Possession, and even a rocking chair scene), but it’s the aesthetics that linger, and send people looking for a non-dopey way of saying “Lynchian”. It’s a hell of a movie.

2) Night of the Living Dead – George Romero (1968)

Like everyone else, I wrote an obituary/MASH note about Uncle George this week. My admiration for his first and (come at me) greatest film is a matter of public record.

One aspect that is less frequently discussed — amid reflections on low-budget filmmaking and race, class and gender in the explosive context 1968 — is the centrality of the film’s lived environment.

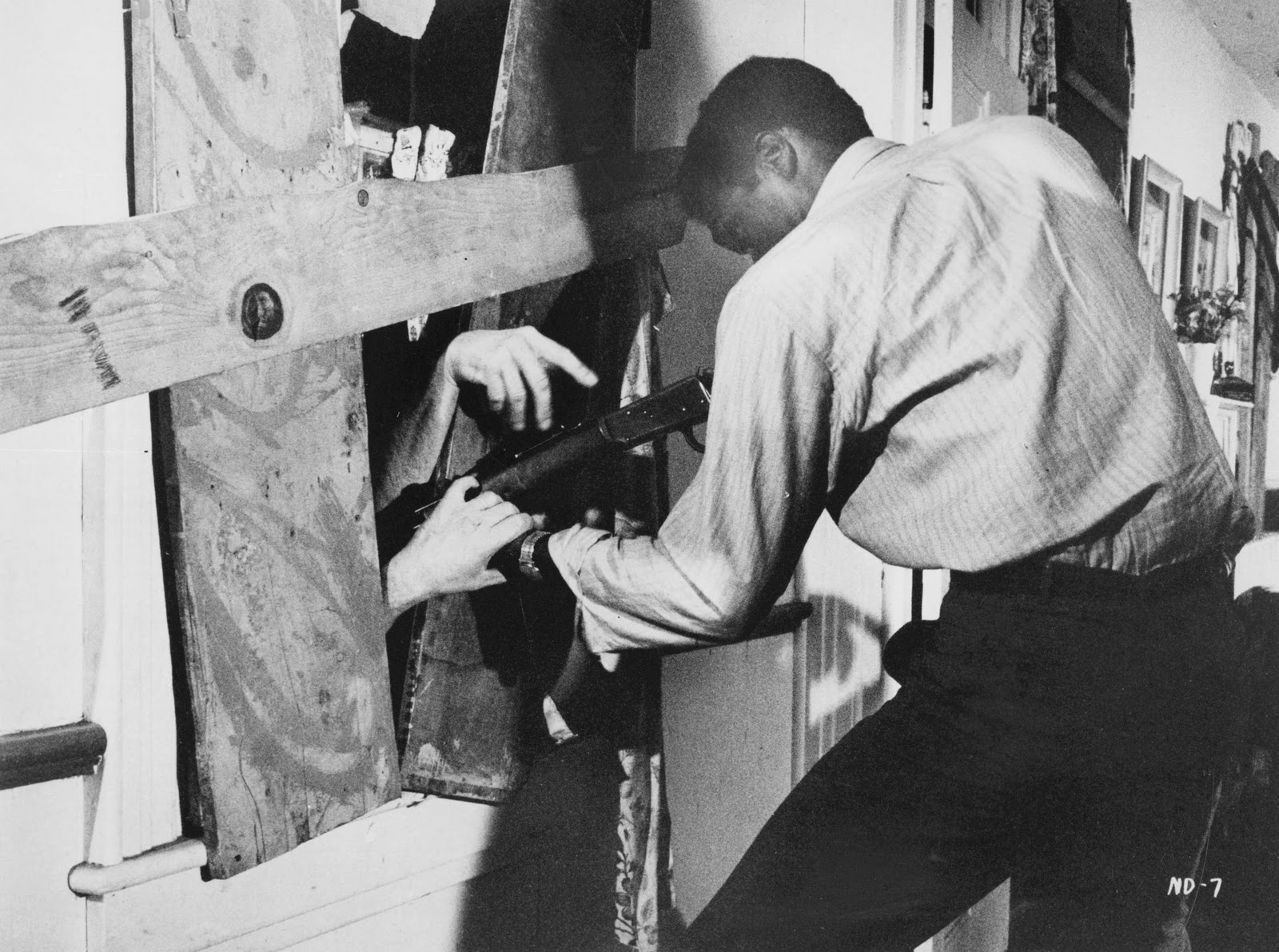

The abandoned house in which our protagonists find themselves plays such a dominant, if limiting, role that it almost seems silly to mention it. It’s that key to the mise-en-scene. The acts of boarding up, and unboarding, are primary narrative devices; so’s the barred basement door, the sheets, the kerosene that provides for molotov cocktails, the gas tank in the yard. Romero mines these family-home signifiers for all kinds of associations and reversals, as our makeshift family-under-siege assumes the exact places and positions of those who’ve already been chased away or consumed.

I could go on about this all day, but I won’t. Let’s all just watch Night of the Living Dead again for the 1000th time.

3) Shivers – David Cronenberg (1975)

Within a decade from the Pittsburgh debut of Romero’s first masterpiece, it had already been subsumed, zombie-like, into the culture. From the perspective of Architectural Horror (seriously, don’t steal this, I am so broke), Cronenberg’s ode to its implications traded the small confines of the bourgeois single-family-home for a Ballardian high-rise, a technocapitalist monument to the well-scrubbed future.

And then released the psychopharmocological sex zombies.

Shivers is not a great-looking film, certainly a world away from the gloss and sheen of later Cronenbergian deep-dives into mind-fuckery, leg-wound-fuckery, and just plain fucking. But that’s half the charm. Nascent ideas about technology, desire, and power infect the whole thing, taking the zombie trope of infection and turning it literally venereal.

Also, to its great credit, Shivers simply makes good on the promise of its creeping dread, that unsettled sense only lo-fi cheapies seem to deliver. Like Usher and Night of the Living Dead, its world is delimited, claustrophobic. But just like the earlier two, it turns out those structural horrors find counterparts in the people around us.