It’s almost a cliche to focus on opening or closing shots of a movie, as though these bookends hold within them all the mysteries the “middle section” (i.e. the film) will explore. But in the case of Fritz Lang’s masterpiece M, that virtuoso opening really does clue us in to the kind of film we’ll be encountering, its aesthetic and concerns.

A vertiginous crane shot reveals a group of children playing in a courtyard, singing a rhyme in a circle (a macabre one, as children frequently seem to prefer) — here, it’s a sort of eeny-meeny-meiny-moe game predicated on a serial killer of children. A mother on a staircase, suddenly shot from below, from the children’s viewpoint, yells at them to stop it with the dreadful theme. They briefly comply, and get back to it as soon as she leaves.

The children, seen from above as though from a hidden vantage point, look small and vulnerable; the mother, seen from below, seems inconsequential, a scolding figure of waning authority. There’s a lingering sense, a mood, that things are not right, that the center can’t hold, that we’re impinged upon by something unseen but felt. A specter is haunting Berlin, off-kilter, off-camera, in shadow, but captivating the public mind. And if the outside world is puzzling, the interiors are just as strange, like the moody, labyrinthine staircase in the tenement where a mother waits anxiously for her daughter to return from school.

M stands at a number of crossroads simultaneously. A visually striking and morally fraught examination of a child murderer and the efforts to stop him, it’s perched between German Expressionism and what would come to be known as film noir; it’s a “talkie” (Lang’s first) that plays like a silent, with a few dramatic and influential deviations in form; and, for many modern viewers, its queasiness, unease, and distrust can’t help but prefigure what was to come, as the frenzy of Weimar collapsed into the epochal horror of the Third Reich.

The killer is Hans Beckert (Peter Lorre, in a career-defining performance). This is not a spoiler. Although we, like most other characters in the film, don’t see Beckert’s face for a surprisingly long stretch of time, it’s never in doubt.

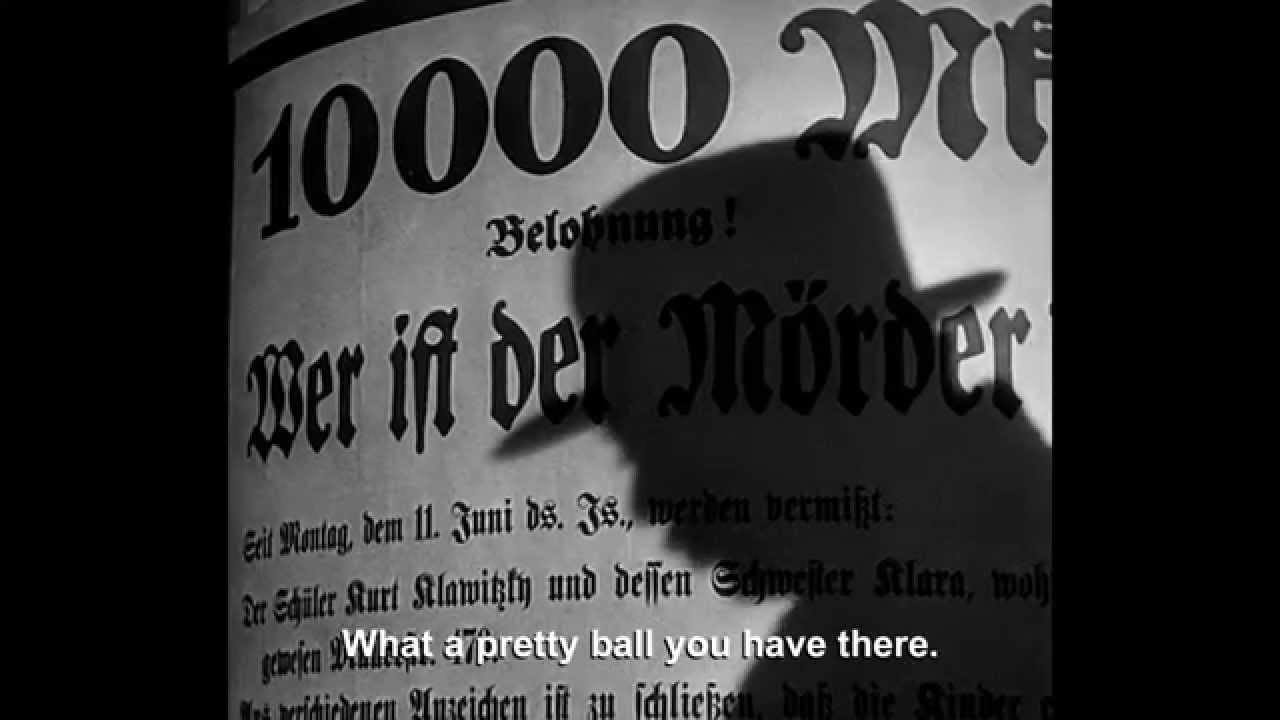

Beckert is a shadow, both there and not there. As viewers, we know him primarily through the sound of his whistling, which he does compulsively, always returning to Edvard Grieg‘s “In The Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt when his murderous impulses take hold. It becomes his calling card, the mechanism by which Lang registers the presence of an unseen, likely malevolent force. This signalling is a commonplace tactic now (think of Omar in The Wire), but as an innovation in early sound film, it’s astoundingly clever. Pair that with the superimposition of his profile, shadowed against his own Wanted poster, and you have the root of a whole library of horror and suspense techniques to follow.

Lang was in the habit, whether he knew it or not, of creating blueprints for genre films. If his Metropolis more or less invented a resonant set of images for dystopian society and high-art sci-fi spectacle four years earlier, it was M that really announced the serial killer narrative and the police procedural, or at least did so for the first time in immediately recognizable ways.

Another celebrated sequence contrasts a conference table of cops, under pressure to capture the killer and soothe public anxiety, with a similar group of criminals, concerned that the killings and the police response are clamping down on business. Lang fuses social critique with an entirely believable narrative in which collectives of interests mirror each other on either side of the law, but its lingering unease is the result of the camera’s twitchiness, its searching, as Tasha Robinson notes:

The whole film is a hunt for a murderer, and Lang’s voyeuristic camera is part of the hunt: The oddball angles make it impossible to forget where the camera is located, giving the sense that it isn’t an objective observer, so much as a spy constantly lurking, sneaking, and prying.

These visual techniques, emphasizing the subjective, co-exist uneasily in M with a focus on the rational. Both cops and criminals have their reasons, and make well-conceived plans to corner and capture their mark. The criminal underworld, we find out, is organized into cells, each representing territory (including the Beggar’s Syndicate, deployed for surveillance on the streets). Meanwhile, the new science of fingerprint identification is introduced dramatically to the screen, a towering image that evokes wonder even after thousands of CSI episodes.

As M shifts into its twinned procedural mode and tale of the criminal underworld, Lang creates a paradox for the viewer. Beckert’s absence from the frame aligns us with those seeking to stop his crimes, but, because of our knowledge of his guilt and compulsion, we are one step ahead of his pursuers, and strangely in the same boat as the murderer. It’s like a particularly accomplished and morally fraught version of The Fugitive, if Dr. Richard Kimble actually did kill his wife.

The film’s final, elaborate sequence is Beckert’s trial, not before a court of law but before the conglomeration of criminals who desperately want to divorce his mania from their more workaday crimes. Sure, they may break the law, but they do so out of necessity, trying to make a living. Child-murder is a step too far, marking Beckert, figuratively and literally, as beyond the pale of acceptable transgression. (Coppola would draw on this heavily in The Godfather, where drug-running is seen as anathema to a more honest criminal code.)

But for Beckert (and his stalwart defense attorney, conjured up by the crooks), this is exactly backwards. He really does have to do what he does; he is not a moral agent, he has no control, whereas the other criminals surely are, and do. He would stop if he could, but is called to commit heinous acts by a force he can’t understand or reject; they show no inclination to abandon their petty transgressions, though they can. How could he be seen as the worse of the two, simply because his crimes are so heinous? If he’s compelled to commit them, as his “lawyer” in the kangaroo court suggests, this is a case for the doctors, not the courts.

For Lang, M was a personal favorite, as he told Jean-Luc Godard 30 years after its release (and who would, 2 years later after that, posit the German master as the philosophically-grounded force of imagination and artistic integrity in his Contempt). Lang’s reasons are curious: from the start, he seemed to view the film’s purpose as pedagogical, and somewhat stripped of the politics that seem so overt now (and probably did then), amounting to a literal reading of its closing lines about looking after the children.

But it’s always hard to take Lang at his word. He wrote that M

point(s) an admonishing and warning finger at the unknown, lurking threat, the chronic danger emanating from the constant presence among us of compulsively and criminally inclined individuals, forming, so to speak, a latent potential that may devour our lives in flames…

Even allowing for hyperbole, this sounds quite a bit more than “looking after the children”. And indeed, Beckert disappears for the entire middle sequence of M. Instead, we witness the social frenzy that ensues when definitive answers aren’t available. Paranoia takes hold, and anyone who so much as speaks to a child is a potential killer. A man is beaten down in the street for telling a young girl the time when she asks. Allegations are hurled, phony leads stymie the police investigation. There’s a precarious sense that mob rule will overwhelm any vestige of reason.

Throughout his career, Lang was deeply suspicious of mob mentality, and this is seen in proto-form in M. Neither the stalwart cops, the careerist criminals, or even the insane Beckert are entirely to blame for the set of circumstances that leads to atrocity. But that “admonishment” Lang speaks of is directed without reservation to the self-appointed keepers of the public good who are so quick to rain down judgment on their fellow citizens. Beckert’s isn’t the only madness in town.

And history surely bears this out. His wife and artistic collaborator Thea von Harbou would become an enthusiastic Nazi; Lang would refuse Goebbel’s offer to become head of UFA, fleeing Germany (like his star Peter Lorre) for a career in Hollywood. The center wouldn’t hold, as it turns out. Millions of murders later, it’s understandable to see M as a prophecy.

But that risks reducing art to simple determinism. Lang would have none of it; he was struck by reports of serial killers in the press, and thought it would make good cinema. But good cinema has a way of naming things in advance, capturing the zeitgeist, and M remains a shocking example. It was instrumental in conjuring up the serial killer movie, the police procedural, even the heist film, and thereby making room for the aesthetics of film noir.

Still. The black-gloved hand on the map, the concentric circles, the notion of total surveillance, mob rule, the failure of decency and the withdrawal to mass suspicion would all prove resonant in the years to come. Even if the prescience was accidental, it’s there in the text. And it’s scary as hell.

Certainly “M” is a portrait of a diseased society, one that seems even more decadent than the other portraits of Berlin in the 1930s; its characters have no virtues and lack even attractive vices. In other stories of the time we see nightclubs, champagne, sex and perversion. When “M” visits a bar, it is to show closeups of greasy sausages, spilled beer, rotten cheese and stale cigar butts.