It is an article of faith among your more generous cinephiles that you should never be embarrassed by the classics you haven’t yet seen. Everyone has blind spots, no one has time to see everything, and a gap in your viewing only indicates how much you have to look forward to! Fair enough. Yet, as a silent film enthusiast, I remain mortified that it took me this long to watch Carl Th. Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc in full. It’s as close to a perfect film as I can imagine.

Why did it take so long? For one thing, Dreyer’s masterpiece is so enshrined in cinematic lore and the collective experience of the image that it can almost feel as though you’ve seen it already. (Speaking for myself, the film’s famous interpolation into Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie may have added to this sense, but more on that later.)

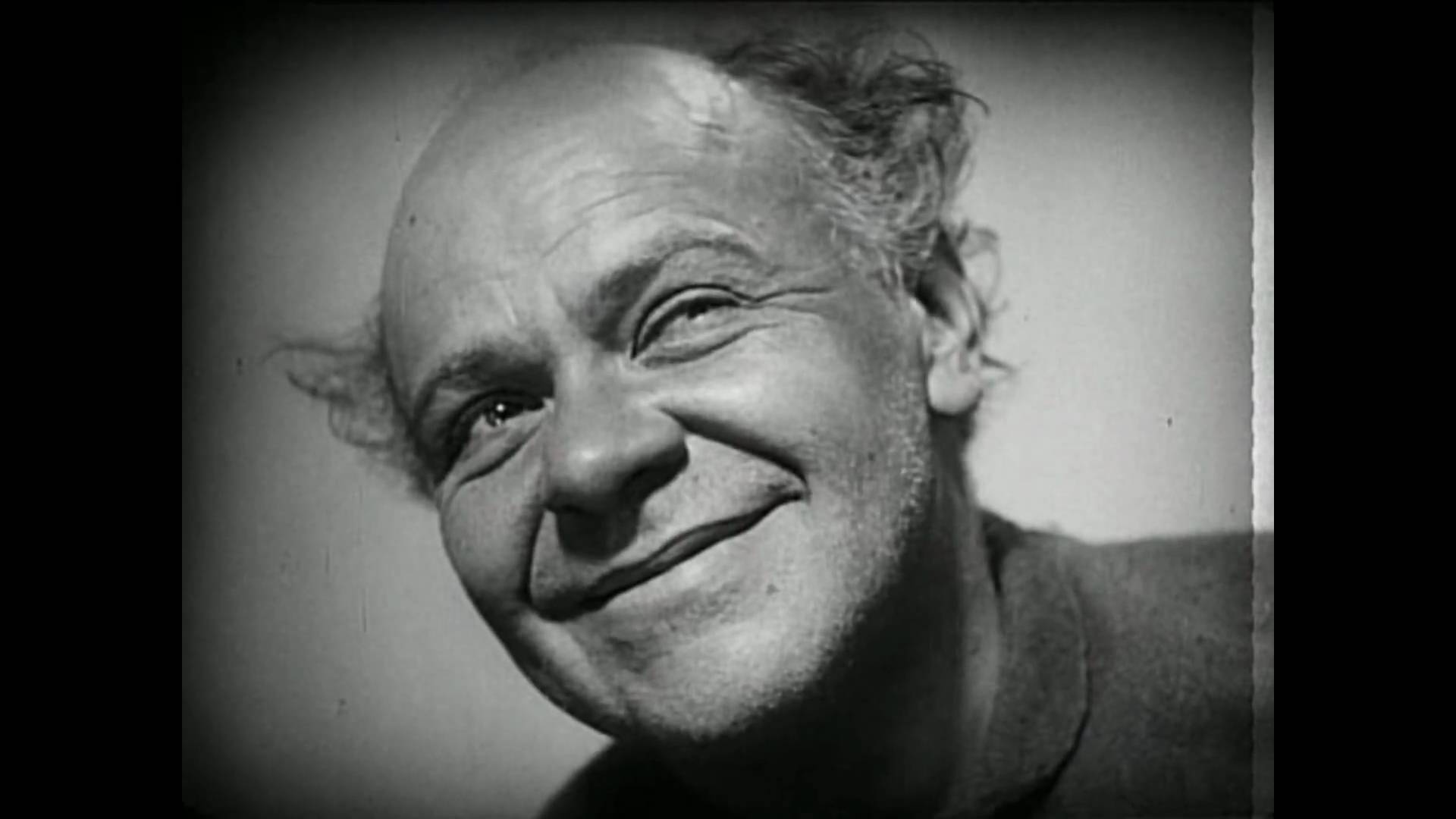

As Joan, shot by Dreyer and cinematographer Rudolph Maté almost invariably in tortured close-up, Maria Falconetti appeared on the screen here in 1928 and promptly vanished, leaving iconic expressions of grace, suffering, and devout fervor for the ages.

Like a handful of images from the Silent Era — Harold Lloyd on the side of the department store building, Keaton miraculously unharmed by the falling house, Chaplin frantically grappling with the mechanical wheel, the Husband and Wife of Sunrise lost in their shared reverie in the middle of a busy street, the mechanical birth of Metropolis‘ Evil Maria … you choose — Falconetti’s face, fearful or defiant or gripped by heavenly longing, lingers in the imagination. Even the imaginations of those, like myself, who arrived to its contemplation late.

The Passion of Joan of Arc is completely disinterested in Joan’s military exploits during the Hundred Years’ War. Instead, Dreyer focuses on her trial for heresy. In real life, her interrogation alone went on for more than a month; in a bold act of compression, Dreyer portrays the events as transpiring over the course of a single day, the better to emphasize the unrelenting cruelty of her inquisitors and her suffering at their hands.

Dreyer’s film is justly famous for the ubiquity of close-ups, but this general fame obscures just how radical The Passion of Joan of Arc is for viewers. David Bordwell, a critic whose formalist analysis can often miss the forest for the trees, is actually essential here. Bordwell notes that “Of the film’s over 1,500 cuts, fewer than 30 carry a figure or object over from one shot to another; and fewer than 15 constitute genuine matches on action.”

The effect is dislocating and jarring, willfully violating the 180 degree rule and leaving the sense of disembodied, slightly off-centered faces suspended in spaces made symbolic by their simplicity and emptiness. We never know quite where we are, or how to look.

The camera pans, generally, from left to right across faces (an incredible scene seems to depict a game of telephone, as inquisitors pass along a question to trap their victim), before cutting abruptly to Joan. Holes were dug in the ground for cameras to emphasize distance and stature; she appears small, her interrogators outsized, enormous, monstrous figures of fear and admiration. (For a more in-depth discussion of these issues, see Matthew Dessem’s profoundly insightful analysis.)

There are few breaks in the action as the film relentlessly hammers home the masculinist power of the state and church brought to bear on a single woman convinced of her visions. Dreyer forbid the use of any makeup, so facial blemishes are emphasized, individual pores highlighted.

The Passion of Joan of Arc can, at times, take on the urgency of a documentary made in the 15th century. (Cocteau: Dreyer’s film is “like an historical document from an era in which the cinema didn’t exist.”)

And throughout it all, there is Falconetti, embodying one of the purest presences in cinema history. Given the tepid response to now-iconic films like Metropolis or others in this series, it’s noteworthy that this was recognized at once by contemporary critics. In The New York Times, Mordaunt Hall praised her performance in 1929 as one “that rises above everything in this artistic achievement,” continuing, in words still difficult to argue with 87 years later:

The scenes where Jeanne is finally led to the stake in the Place du Vicux Marché, Rouen, are agonizing in their remarkable realism, and this is, of course, one of the reasons that Britain has banned “The Passion of Jeane d’Arc.” America benefits where Britain loses, for as a film work of art this takes precedence over anything that has so far been produced. It makes worthy pictures of the past look like tinsel shams. It fills one with such intense admiration that other pictures appear but trivial in comparison.

The story behind The Passion of Joan of Arc is nearly as famous as the film itself. Dreyer had decided to make a film about a French woman; the Maid of Orleans was reputedly chosen by drawing straws. He spent a year or more in research on the topic, deciding eventually to ignore her military exploits and focus entirely on her trial at the hands of the disbelieving male prelates and to base the film almost entirely on the newly-famous transcripts of her trial.

Dissatisfied with his casting options (Lillian Gish was briefly considered, further angering the French clerics who already felt the agnostic Danish director had no business making this film), Dreyer discovered Falconetti in a comic stage performance and decided he had found his Jeanne.

The film was shot chronologically, a highly unusual approach — indeed, Falconetti had hoped this would buy her time to talk Dreyer out of having her cut her hair at the film’s end. No such luck.

Enormous amounts of studio money were used to build a replica Medieval village which Dreyer barely shows on screen, to the chagrin of his financiers. The intention, apparently, was to force the cast to feel they were of the moment with the subject at hand, that they were in fact living centuries prior. By all accounts, it worked, leading to a kind of ecstatic mania among the performers.

Dreyer was notoriously ruthless and intent on realism, in ways that would never be allowed today (nor should they) — encouraging real tears, having Falconetti kneel for hours on stone, the deployment of actual fire, and so forth.

And for all this trouble? The Passion of Joan of Arc was heavily censored, rejected by the Church, banned in England, and eventually destroyed. Dreyer painstakingly recreated the film from outtakes and the remaining footage. This version, too, was destroyed.

Bastardized copies, disavowed by the director and panned by critics as unrepresentative of the original intent, circulated for years. Then, in 1981, a miracle occurred: a nearly pristine original was discovered … in the closet of a mental hospital in Oslo! How it got there remains a mystery. The strange overlap of thematic treatments of visions and possible madness in the film with the location of its discovery is both entirely appropriate and entirely bizarre.

It seems almost too perfect, but then so does The Passion of Joan of Arc. This is uncompromising filmmaking, a perfect combination of subject, performance, and auteurist approach. (How auteurist? Dreyer remarked, “Allowing others to prepare a scenario for a director is like giving a finished drawing to a painter and asking him to put in colors.”).

The sets by Jean Hugo and Hermann Warm, who previously handled this role for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, are striking in their austerity. The effortlessness of the camera’s movement indicates an entire crew committed to a singular vision.

In the end, that vision is, more than anything else, the human face. When Godard’s Nana retreats to the cinema in Vivre Sa Vie, it is of course The Passion of Joan of Arc that she attends, her tears in the audience mirroring the close-ups on screen. Ebert quickly explained that this is because both are “about a woman judged by men.” Perhaps. Others have found more formal (and more convincing) explanations. The lingering impression in both cases, on the most basic level, is the fascination with those flickers of life, light, and sorrow that the face reveals in darkness, the ways we connect to and find ourselves in the images before us.

For Dreyer, this was the foundation of the cinema. More than narrative, more than Epstein’s photogénie or the later Cahiers emphasis on mise-en-scène. For Dreyer, “Nothing in the world … can be compared to the human face. It is a land one can never tire of exploring. There is no greater experience in a studio than to witness the expression of a sensitive face under the mysterious power of inspiration. To see it animated from inside, and turning into poetry.”

The Passion of Joan of Arc begins with a text, focuses on an interrogation, passes through torture at the hands of a threatened leadership, and ends with a death in flames, as birds, symbols of grace and transcendence, blend into clouds.

But it’s Falconetti and Dreyer’s great triumph that the cumulative impact of their film is resolved into a single human face containing multitudes, alone in the frame but imbued with the inexpressible wonder of life as it is lived, as it is represented, and as it might be. All arguments flitter away like those same birds. There are only faces, and then there is sky.

To modern audiences, raised on films where emotion is conveyed by dialogue and action more than by faces, a film like “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is an unsettling experience–so intimate we fear we will discover more secrets than we desire. Our sympathy is engaged so powerfully with Joan that Dreyer’s visual methods–his angles, his cutting, his closeups–don’t play like stylistic choices, but like the fragments of Joan’s experience. Exhausted, starving, cold, in constant fear, only 19 when she died, she lives in a nightmare where the faces of her tormentors rise up like spectral demons.

Perhaps the secret of Dreyer’s success is that he asked himself, “What is this story really about?” And after he answered that question he made a movie about absolutely nothing else.