In The Nightmare (2015), Room 237 director Rodney Ascher updates his enjoyable 2012 portrait of a handful of people with some … colorful interpretations of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining, mapping similar themes onto an entirely different, much scarier vision.

The earlier film allowed ample, hilarious space for these Kubrick obsessives to present their wildly improbable visions of his true intent, but at the same time it served as an examination of the ways in which meaning is created. It was a movie for film-nerds and horror aficionados doubling as an inquiry into the mysteries of how we think, and how closely theorizing resembles paranoia.

Similarly, The Nightmare is a documentary about a phenomenon – sleep paralysis – but also about how that phenomenon is experienced, perceived, explained, and represented. And it’s often as scary as any of the horror movies that draw on it.

And what is sleep paralysis? That’s easy – it’s my new greatest fear! Apparently afflicting 6.2% of the general population, it’s a condition that renders sleepers suddenly conscious but immobile, unable to move or speak for varying degrees of time. As the film explains in detail, it’s also associated with auditory and visual hallucinations that are remarkably similar from person to person throughout the world. Unsurprisingly, this leads some to suspect these aren’t hallucinations at all, but something different … more primal, or more supernatural, or more demonic. In any case, a lot more than a slight psycho-physical reaction.

Ascher – who, it turns out, experiences this himself – again lets his subjects talk at length, and often fascinatingly, about what it feels like to be trapped in their own bodies and minds, somewhere between sleep and waking. And it sounds absolutely terrifying.

Most report a buzzing, like bees or television static, and feelings of pulsing electricity that sometimes morph into what many are convinced are physical presences. For one man, these shadowy figures resemble our cartoon visions of aliens, all bug-eyed and sinister-mouthed, and he comes to believe that many reports of alien abductions might be related to undiagnosed sleep paralysis.

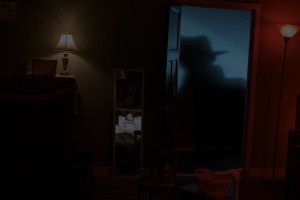

For many others, they are flickering shadow-men looming in corners or over their bed, or felt just beyond the door – it is weirdly common for people to report that these are henchmen of another figure, often wearing a hat or something that distinguishes them from the other two. They are always shadowy, in any case, often come in a set of three, and uniformly carry with them a sense of malevolence or outright evil.

The film reenacts many of the episodes described. At first, this is a funny and slightly goofy touch, like if Errol Morris had made The Thin Blue Line about demons. The reenactments also draw on the sort of “Alien Autopsy”-style programs you might find on your local cable station late at night – they’re intentionally broad, and almost seem to be poking fun. But as the film progresses, and the commonalities become apparent, that goofiness vanishes and is replaced by something a lot more like horror movies, jump-scares and all.

This is the film’s deftest touch – it examines not just sleep paralysis, and not just how people desperately try to explain their experience, but also how our perceptions are shaped by representations of them. They draw on film for context – it’s like Jacob’s Ladder, it’s like Communion, it’s a lot like A Nightmare On Elm Street. Ascher himself details how a figure momentarily included in a horror movie credit sequence uncannily resembled a figure he saw lurking in his room, while paralyzed in his bed.

The question might be, “Which came first, then?” It isn’t answered, probably because it can’t be. Did the creators of modern myths draw on these experiences, or are these experiences informed by their creations? Or something else entirely? Why do a man in England and a woman in Southern California who’ve never met see and feel the same presences as they struggle to wake up? Why have similar tales been told all over the world for hundreds of years?

Of the subjects, some grapple with it to this day, and expect it to get worse until they die. Some rationalize it, and associate the startlingly singular descriptions to Jungian archetypes. One woman discovers the presences can be good as well as evil. Another finds God, and believes she can will these actual demons away with the name of the Lord. Ascher doesn’t present a thesis or resolution, and the film is all the more disturbing for that.

At the end of every day, everyone lies down and retreats into their head alone, into their thoughts and fears, the unexplainable and the things we can’t will away so easily. There’s no pushing things out of your mind when your mind is in charge. And for a significant chunk of people, this also means falling into a spectral realm where shadows threaten, electric pulses buzz, and distant screaming is heard, a realm they feel they may or may not be able to escape.

Explanations only go so far. Good luck falling asleep after The Nightmare.