Eli Roth is a man out to generate strong emotions. Whether through his gleeful repurposing of ’70s cannibal exploitation schlock, or his recent, unfortunate foray into trolling what the internet has dubbed Social Justice Warriors (that is, generally speaking, people who care about things at all), Roth’s not the easiest guy to champion. But, whether by accident or design, he made something of a horror masterpiece with Hostel, shot through with anxieties about Ugly American imperialism and (yes) animal rights themes.

Hostel is routinely lumped in, and not unjustifiably, with the much-derided “torture porn” genre that flourished at the time, a weirdly resonant U.S. film trend almost impossible to divorce from the Bush era that grounded it. (Like Scott Tobias, I prefer the term “extreme cinema” to “torture porn,” but I’m willing to let it go for our purposes here — there’s a lot of torture in Hostel, after all.)

Roth creates a subterranean world of torture-for-hire, a shadow economy where wealthy folks from around the globe can pay to exact their worst impulses on kidnapped travelers. We follow three young Americans as they backpack through Europe, following in the footsteps of either literary heroes (“Oh, you’re from Prague? Kafka!”) or simply pursuing sexual hijinks, like any number of young morons before them. It doesn’t end well.

A chance encounter in Amsterdam leads our knucklehead crew to a hostel in a Slovak city that doubles as a holding facility. They are wined, dined, and bedded by lovely women, but it’s simply a fattening before the slaughter. (We could dub it “free range” … or, if you like, the “clean side” that will be contrasted with the “dirty” one.) People check in but never seem to check out; they just vanish.

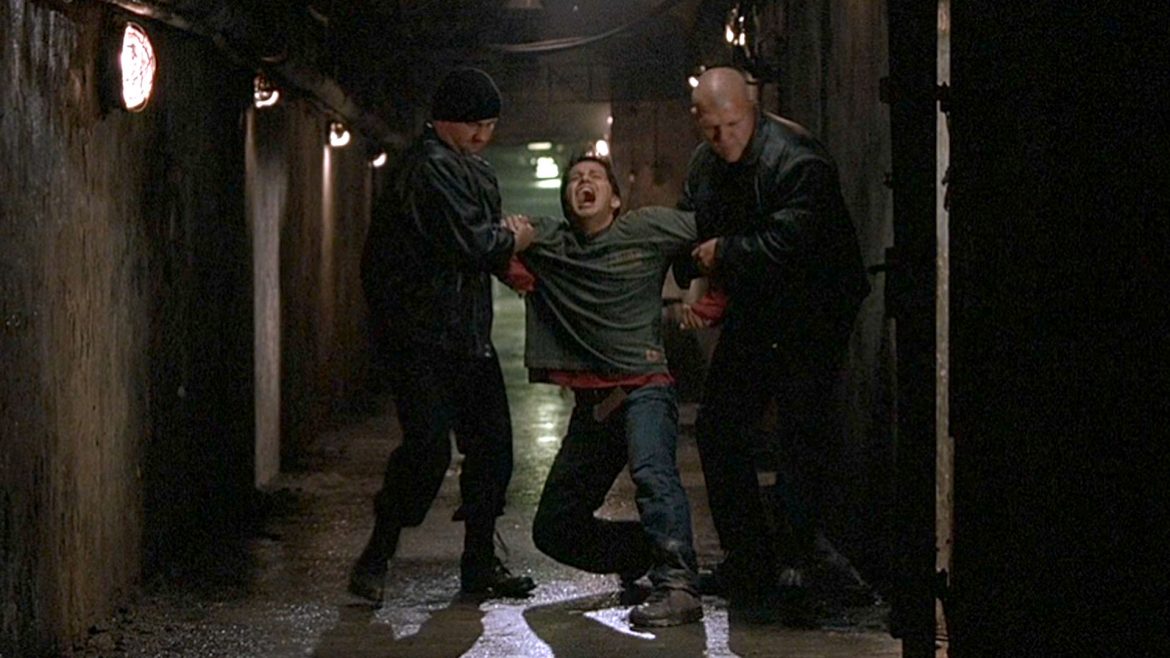

As the protagonists’ numbers dwindle, we realize why: there really is an entirely different world underground, a network of cells where, for a fee, the global moneyed elite can have free rein to do their worst to the bodies of the imprisoned. And so they do. Anti-Americanism holds supreme, but there are victims of other nationalities, too: the only real connecting thread between them is their subservience to the whims of capital and the horrific, no longer sublimated, cruelty of man.

Josh (Derek Richardson) is the audience stand-in among the travelers, at least in Hostel‘s initial framing, but his buddy Paxton (Jay Hernandez) will become primary. He’s also, explicitly and notably, a vegetarian.

On a train, the pair have a run-in with the film’s primary villain, unbeknowst to either (or to us). When Paxton refuses an offer of meat and the creepy companion begins shoveling it into his mouth with bare hands, we get this exchange, which reverberates throughout the rest of the film:

Paxton: …you need a fork there chief?

The Dutch Businessman: No. I prefer to use my hands. I believe people have lost their relationship with food. They do not think “this is something that died for me so that I would not go hungry.” I like that connection with something you die for. I appreciate it more.

Paxton: Well I’m a vegetarian.

The Dutch Businessman: I am a meat-eater. It is human nature.

Paxton: Well I’m human and it’s not my nature.

Hostel emphasizes this divide over the course of its narrative. The underground lair is divided into pens, not unlike the stalls in The Herd (a film that owes Roth a substantial, slightly ironic debt). The counter-intuitive notion that individual suffering is redeemed through individual participation also weirdly echoes the still-fashionable focus on “humane slaughter” among the more New Age-inclined, hip sectors of the omnivorous world, who argue the real problem is not the killing but its industrialization. The problem is the distance between victim and murderer; a more honest, ethical approach would be to get blood on our own hands, to feel life bleed out. Or so we are told.

The reduction of humans to objects of torture has clear political connotations in Hostel, but it also invokes the networks of power that guide human treatment of nonhuman animals.

In fact, Hostel‘s real shock comes through that elision. The victims’ powerlessness and the overt pleasure taken in manipulation of their flesh by their captors can’t help but call to mind a slaughterhouse, with its casual viciousness and the glee we sometimes see revealed in undercover videos on the part of workers. Roth emphasizes this through additional footage of carcasses on trolleys and floor-drains for offal.

To a certain degree, Hostel only takes the central conceit of the “hunter becoming the hunted” to a lunatic extreme. The final, cliched line of the execrable Cannibal Holocaust, a film so full of actual animal slaughter footage that it qualifies as snuff, seems to echo: “Who are the real savages anyway?” It is no accident that Roth is an enormous fan of that Ruggero Deodato schlock stand-by, or that Deodato himself makes a cameo in Hostel‘s sequel, in a scene in which he is filleting and eating a man alive. Roth can be accused of many things; subtlety is not one of them.

But the fascinating thing about Hostel is how these themes of power and domination are merged and integrated with larger questions of blowback from Bush-era “enhanced interrogation” techniques. There is an uncanny sense that, in the age of late-capitalism, it’s not too far a step from the slaughterhouse to the torture pen, from Abu Graib to torture-for-hire.

There are latent killers everywhere we look, and men who will argue the only real problem is that we’ve contracted out the murders. “I like that connection,” they will tell us, right before slamming closed the iron cell door that places us too, irrevocably, on the chopping block.