When I began writing about horror cinema as a form of oblique artistic grappling with our real-life treatment of nonhuman animals, it was with enthusiasm and several convictions. First, that this approach would merge two of my primary interests, philosophical issues of animal rights and their aesthetic representation and also scary movies. And second, that no one was really addressing these themes in much detail.

Well, one out of two isn’t bad.

As it turns out, Gunnar Theodór Eggertsson — then a student at the University of Iceland and now a professor — spearheaded just such an investigation a decade ago. His paper “Animal Horror: An investigation into animal rights, horror cinema and the double standards of violent human behaviour” is a fascinating look at how these tropes play out, rigorously argued and entirely persuasive.

Beginning with a look at Georges Franju’s notorious Le Sang des bêtes (Blood of the Beasts) — which Eggertsson rightly calls “a landmark in the animal rights movement for its realistic depiction of behind-the-scenes meat production” that reveals “the unknown reality that exists under the surface of suburban life and vividly places it right in front of the unsuspecting viewer” — the paper lays out its ambition in clear terms. An analysis of these horror tropes will:

creat[e] a theoretical bridge between certain distinctions of the extreme horror genre and animal rights theory [… and] analyze parts of horror cinema as representative of animal treatment. […] [T]he violent act and its representation […] can be read as being symbolic of the violence that occurs against other species all over human society and is justified by the terms of human pleasure (be it for consuming, decorating, sport or clothing). By the end of this essay I will have argued e.g. that criticism of violence in a film such as The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (USA: Tobe Hooper, 1974) is arbitrary if it is not made out to include other species.

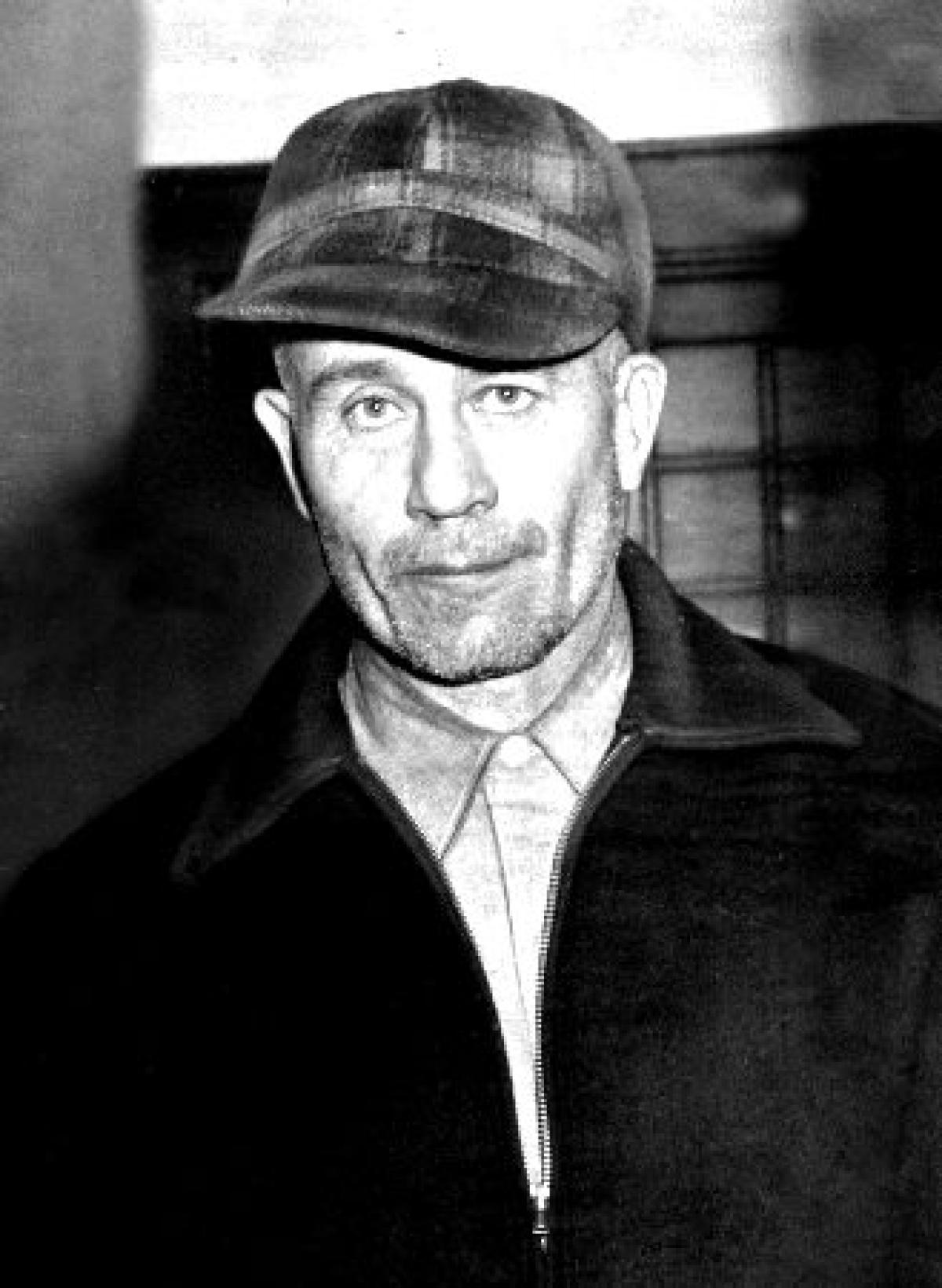

It’s no accident that both Eggertsson singles out The Texas Chain Saw Massacre for his thesis; I did the same earlier in this series. With its overt emphasis on slaughterhouse work and the resolutely instrumental aspect of Ed Gein-inspired brutality, Tobe Hooper’s text is perhaps the most unavoidable in this sort of discussion.

We both also address Hostel, an example of horror cinema that goes out of its way to connect “losing touch” with the instrumental use of nonhuman animals and the brutality inflicted on their human surrogates through a horror lens. In Hostel and elsewhere, animality is the absent referent that structures such treatments, lurking barely below the surface and infusing the signifiers with a terror born of a return of the repressed.

Eggertsson takes a look at several other films — Wolf Creek, Calvaire, Zombie Honeymoon, The Hills Have Eyes, Les Yeux Sans Visage (Franju again)– but the really interesting thing is how he structures the argument.

Following animal rights theorist Tom Regan, he draws a distinction between moral agents and moral patients; that is, “individuals who have various sophisticated abilities, most importantly the ability to apply impartial moral principles to determine what morally ought to be done in a given situation and to freely choose to act or not to act as their conception of morality requires them to act” and those who “do not possess the prerequisites that would enable them to make moral decisions about the extent of their actions and can therefore not be held morally accountable for what they do.”

The classic view here, inscribed in law and buttressed by general notions of common sense, would include sentient, adult humans on the one hand — who are morally culpable for their actions — and all the other groups (very young children, the mentally disturbed or challenged, nonhuman animals) who are not. We would not try a lion for the murder of a gazelle; the idea is absurd. If a very young child commits a grievous act, our moral reasoning generally excuses them from true culpability, which is why we (hopefully) do not put 5 year olds in prison for, say, candy bar theft.

For Eggertsson, then, the most relevant considerations for that “theoretical bridge between certain distinctions of the extreme horror genre and animal rights theory” lies in situations where the substitution of human for nonhuman animal involves moral agents. This would tend to rule out most zombie films, in which the zombies can’t rightly be blamed for their impulse to eat brains and bodies. (Zombie Honeymoon is an exception for reasons explained in the piece.) Werewolves presumably would fall into the same quandary. Vampires would also be a questionable category, assuming they need human blood to subsist. All such “dual creatures” would be more akin to carnivorous predators in this moral calculation, at least after moments of transformation.

This is a point on which Eggertsson and I differ. The rigorous distinction between moral agent and patient is appropriate in the context of his paper, but it shuts off from consideration a number of avenues. There is clearly something going on in the cinematic imagination where zombies and vampires are concerned, less because of their moral status and more because of boundary-blurring between rationalist humanity and “sub-rational” animality. If Texas Chain Saw and Hostel posit human substitutes for nonhumans in visions of our interactions, the classical ideas of vampires, werewolves, and zombies all wonder what it would be like if we were of a piece, both human and nonhuman at once. This is part of an imaginative continuum.

Even more than that, there is the entire genre of the “vegetarian vampire,” an explicit linking of concerns with a long history and a recent resurgence, whether in Buffy/Angel, the Twilight films, True Blood, or even Count Duckula. Future entries in this series will tackle some of those ideas.

But Eggertsson’s essay is a must-read for anyone interested in these topics, a real contribution to the discourse. By examining the animal rights subtexts of a maligned genre, he effectively seeks to recuperate extreme horror cinema, wrenching it from the bloody talons of its detractors and revealing the deep anxieties that underwrite its tropes.

As long as animals are being slaughtered, we will tell stories about them, one way or another. Rather than castigating the violence on our screens, we should take a close look at how it relates to the violence in our lives.