It was about 20 minutes into the interminable Keanu Reeves / Winona Ryder vehicle Destination Wedding that my whole being shuddered and rejected it, like an immune system refusing a skin graft.

It wasn’t just the grating banter from otherwise likable film presences, or the lazy ugliness of its images, or their coddling familiarity. Destination Wedding, a rom-com without romance or comedy, congratulates itself on plotlessness but is mired in the worst quicksands of narrative. It’s a plotty plotlessness, shots still as Columbus without anything to look at but the corners of the screen, where we insert our own expectations of narrative resolution. They are fulfilled, banally, before credits roll, and we walk away having achieved the level of viewer participation to which our cinema aspires: the ability to recount a story.

Twelve hours later, I found myself instead in the silent darkness of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive‘s Barbro Osher Theater, as the radically fractured, mysteriously cohesive 16mm films of Warren Sonbert washed over us. Hundreds of shots, edited without conventional continuity or narrative thrust, constitute these films. Sonbert was called a diarist, which he’s not, and his compositions (for they are composed, like songs in which images are notes) summed up as “explosions in a postcard factory,” a serious misreading. But I kept thinking back to Destination Wedding, and marveling at what we’re willing to settle for: cinema, with its vast arsenal of tools for sorcery, invocation, mythic resonance, reduced to scenarists’ notes.

“Oh, I haven’t seen that one; what happens?” We might as well report back from a museum visit with a count of apples in the still lifes.

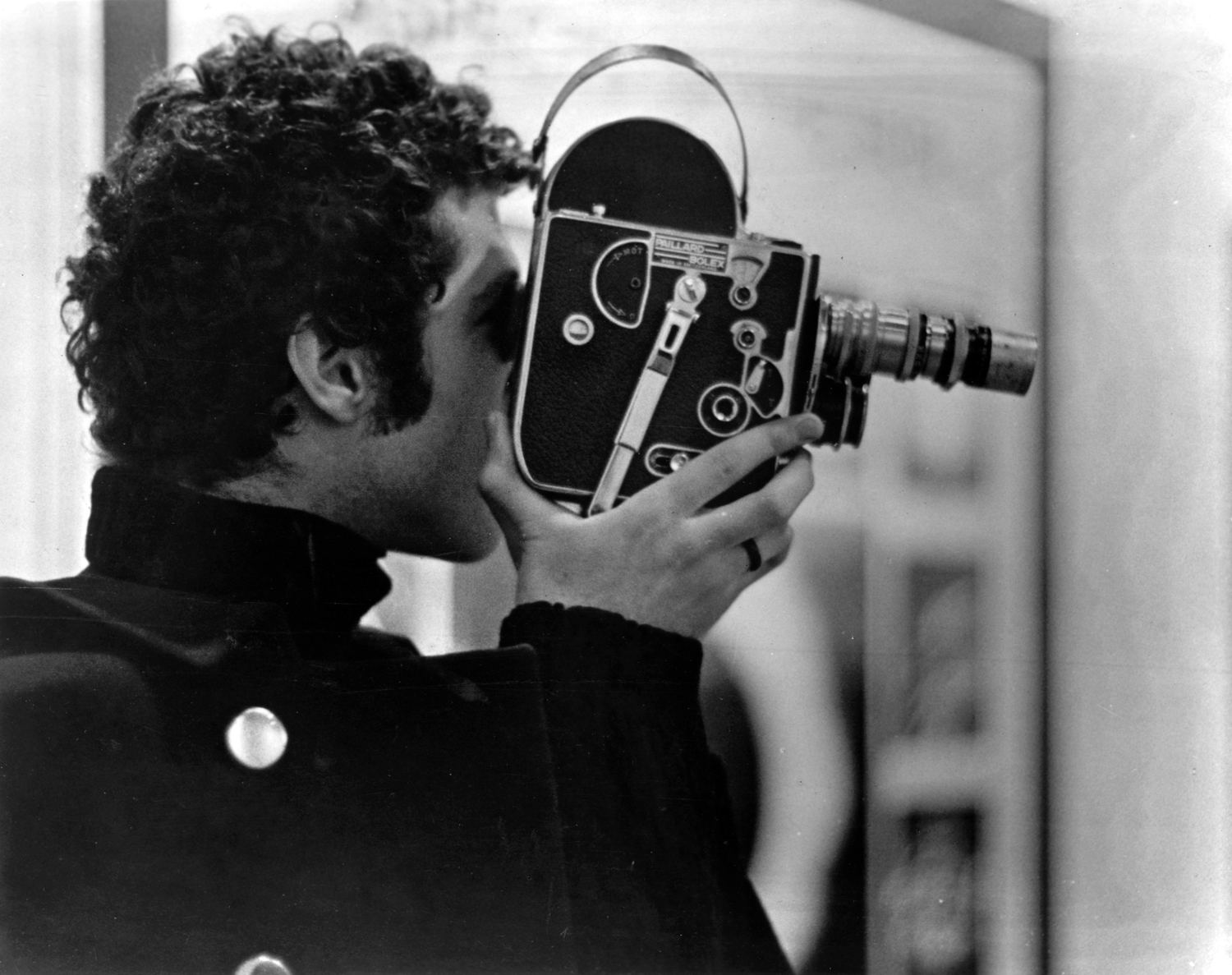

What happens in Sonbert’s work? (BAMPFA screened the early, Warhol-adjacent Hall of Mirrors (1966), and then Divided Loyalties (1978), The Cup and The Lip (1986), and Short Fuse (1991), all of which are more properly in Sonbert’s trademark style of rapid-fire montage.) Well, activity happens. People happen. Parades, circuses, hang-gliding, kittens, tigers, cafes, protests, military displays, children’s basketball, plane takeoffs and landings, train tracks receding. There’s an emphasis on youth and vitality, sex, intimacy. There are graveyards and ACT-UP militancy. There are tightrope walkers and gay rights rallies and dogs waiting for scraps at picnic tables. There’s a surgery and a gynecological exam and surfers in the ocean. There are light leaks, a feeling of ephemerality. There is, blessedly, not a story in sight, but a guiding feeling of symphonic surprise. Anything could happen and, if you have a camera, you might catch some of it. Sonbert had a camera.

What happens in Sonbert’s work? (BAMPFA screened the early, Warhol-adjacent Hall of Mirrors (1966), and then Divided Loyalties (1978), The Cup and The Lip (1986), and Short Fuse (1991), all of which are more properly in Sonbert’s trademark style of rapid-fire montage.) Well, activity happens. People happen. Parades, circuses, hang-gliding, kittens, tigers, cafes, protests, military displays, children’s basketball, plane takeoffs and landings, train tracks receding. There’s an emphasis on youth and vitality, sex, intimacy. There are graveyards and ACT-UP militancy. There are tightrope walkers and gay rights rallies and dogs waiting for scraps at picnic tables. There’s a surgery and a gynecological exam and surfers in the ocean. There are light leaks, a feeling of ephemerality. There is, blessedly, not a story in sight, but a guiding feeling of symphonic surprise. Anything could happen and, if you have a camera, you might catch some of it. Sonbert had a camera.

It’s not merely that Sonbert avoids narrative. The cuts themselves undermine it. Like Brakhage, Sonbert’s editing is intuitive but without a “point,” in the hectoring sense of Eisensteinian montage. Its only allegiance is to rhyme, echo, and trigger, though it’s not without humor. (A communist gathering spliced with a group of mice running in circles, recalling Eisenstein’s elision of Trotsky and a peacock, only shows that Sonbert’s rules are made to be broken.)

There’s something profoundly liberating in its true plotlessness, something akin to the West Coast language poets with whom Sonbert was associated (or, to return east from whence he came, something like a feint at No Wave artlessness). We live in plotty times, strangled by the endlessly recursive, preening narratives of the corporate comic book empires, both too fan-servicingly ironic and blithely, falsely earnest. (“Earnestness kills art,” a sound recording of Sonbert asserted in between the satisfyingly material clicks of the projector, like a mischievous voice from the grave.)

Watching Sonbert’s films call to mind a quote from Hirokazu Kore-eda: “Films need people more than stories. Landscapes also harbor emotions. Music can blow like the wind through a scene.” For an exhausted viewer in an exhausting age, it’s ironic that 20-minute films composed of hundreds of cuts feel like a return to something simple.