With his expression of thoughtful weariness and a face that inevitably brings to mind the word “hangdog,” Vincent Lindon owns every moment of Stéphane Brizé’s recession-era morality play The Measure of a Man (La loi du marché). As protagonist Thierry Taugourdeau, Lindon, who won Best Actor at Cannes and a César for his performance, is expertly nuanced in the role, frequently silent but always comprehensible, a downtrodden Everyman. He’s a fundamentally decent man forced into awkward and uncomfortable social positions, bruised by the ruthless machinations of capitalism while trying to do right.

The Measure of a Man opens with Thierry in tense conversation with a job recruiter. Laid off from his previous factory position, Thierry has been out of work for many months, taking training courses that lead nowhere, suffering through interviews for jobs he clearly knows he will not get. The frustration is showing.

His former coworkers, similarly laid off for a “downsizing” they rightly suspect has more to do with corporate profit than workplace necessity, have lawyered up, but Thierry is tired of this fight. He has a wife, a mortgage, a disabled son, and dwindling savings. He’s less out for the satisfaction of legal revenge than simply stable employment and the self-worth it seems that entails. Indeed, as he begs off the struggle against his old bosses, he explains it succinctly: it threatens his “mental health.”

As Thierry dutifully pursues options — a horrifically uneasy Skype interview, a meeting with a no-nonsense financial advisor, a cringe-inducing roundtable discussion to improve his “presentation” and job prospects — cinematographer Eric Dumont keeps him in shallow focus. It’s a smart choice, all the better to observe the naturalistic flickers of anxiety that cross Lindon’s face, while the camera underscores them with nervous, near-vérité quivers itself. Comparisons to the Dardennes are warranted (indeed, The Measure of a Man would work well paired with 2 Days, 1 Night), but Brizé, Dumont, and Linton have separate qualities to recommend their work here.

When he finally does land a gig as an underpaid security guard at a grocery store, The Measure of a Man takes a decisive turn, from humanist, Dardennes-inspired narrative to social critique. Thierry has far more in common with the petty thieves, struggling shoplifters, and exploited co-workers just trying to get by than he does with the bosses who pay him a pittance to rat them out. Brizé emphasizes the total surveillance of the supermarket, the ubiquity of cameras making it seem less a place of business than a prison. A reckoning is coming.

When it does, it is, like the film as a whole, a decidedly understated affair. But the message, never hammered polemically but emerging with sad inevitability from Lindon’s performance, is clear enough. The film’s French title translates as “the law of the market.” For anyone caught up in the moral compromises and routine degradation of late capitalism, it will come as no surprise that this law is merciless. Whoever it benefits, it’s not the workers. When Thierry makes his decision — quietly but resolutely — it’s a declaration of allegiance, to human value and self-worth outside the artificial demands and draconian restrictions of bosses everywhere.

Quick Links

The Invitation: On first viewing, I was a bit luke-warm on the latest from Karyn Kusama (Girlfight, Æon Flux, the Diablo Cody-penned Jennifer’s Body), but it’s grown on me and has plenty to recommend it. Slightly unequal parts friend-reunion drama, bloody climax, and creepy final reveal, Kusama builds the dread with aplomb, focusing on the disparate relationships and buried tensions among the ensemble with enough nuance to generate investment in their individual fates. If The Invitation overplays its hand a bit by beginning with a clunky metaphor and starting from a position of obvious unease (seriously, who would stick it out with these creepers as hosts?), the film proceeds skillfully and sticks the landing. It’s worth a late-night watch.

Battle Royale: Long before The Hunger Games pilfered many of its central conceits and saddled them in service to a milquetoast love triangle, Battle Royale was the standard-bearer of the dystopian kids-killing-kids-for-sport genre. While its distant American cousin built up to a revolutionary metaphor increasingly enamored with itself, Battle Royale was content to stick to the basics: deranged glee, gore, and some earned pathos. It’s superior in every way.

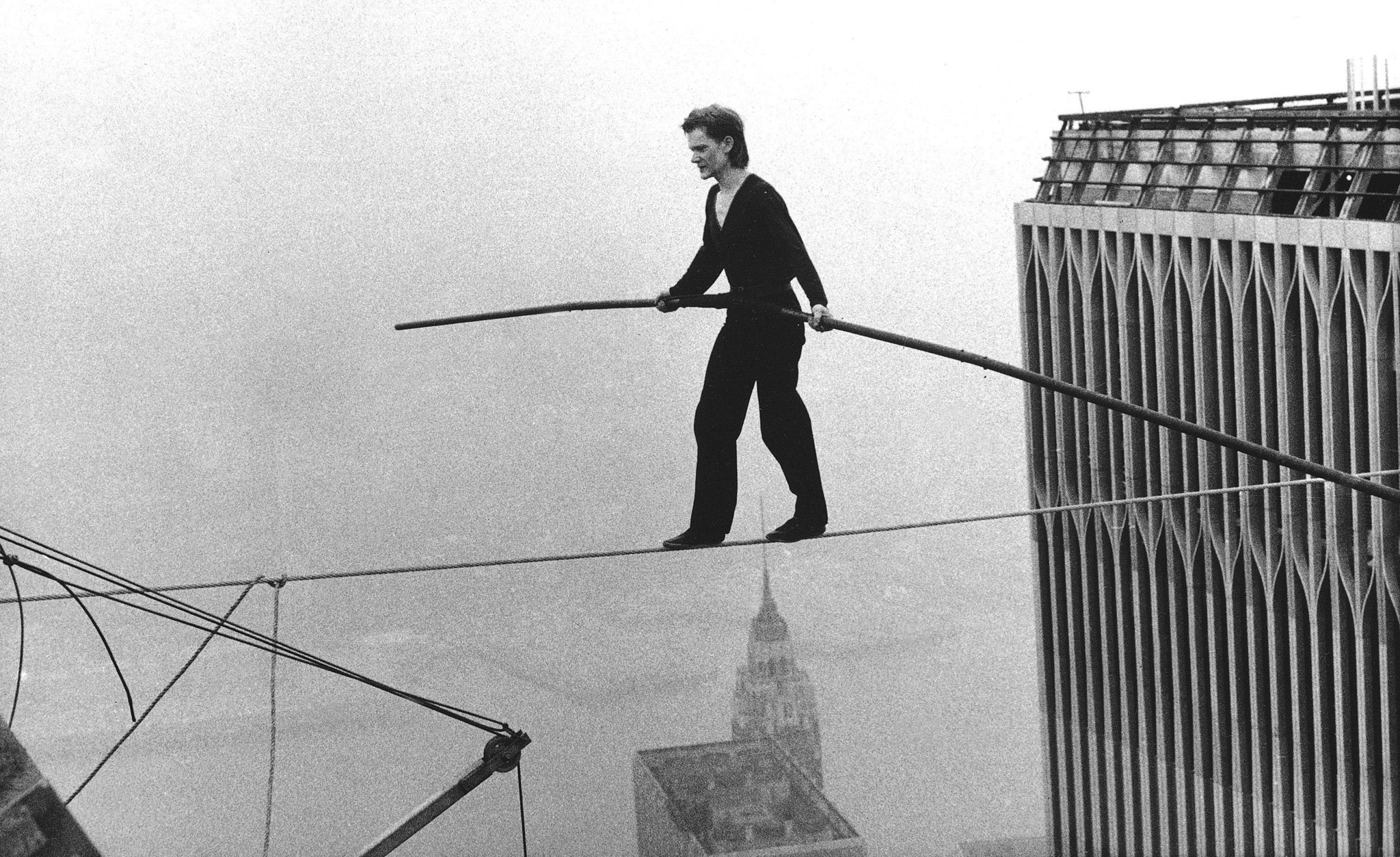

Man On Wire: James Marsh’s time-capsule portrait of daredevil / lunatic Philippe Petit, who famously (and very illegally) walked a tightrope between the Twin Towers in 1974, is gripping and honest. Petit comes off as a man obsessed, fearless, incredibly charming and, maybe for that reason, rather smarmy. But there’s no denying his commitment or dedication to cheating death. The footage of his stunt alone is worth a viewing, a white-knuckle escapade that makes you never want to set foot on a roof again. In a good way.

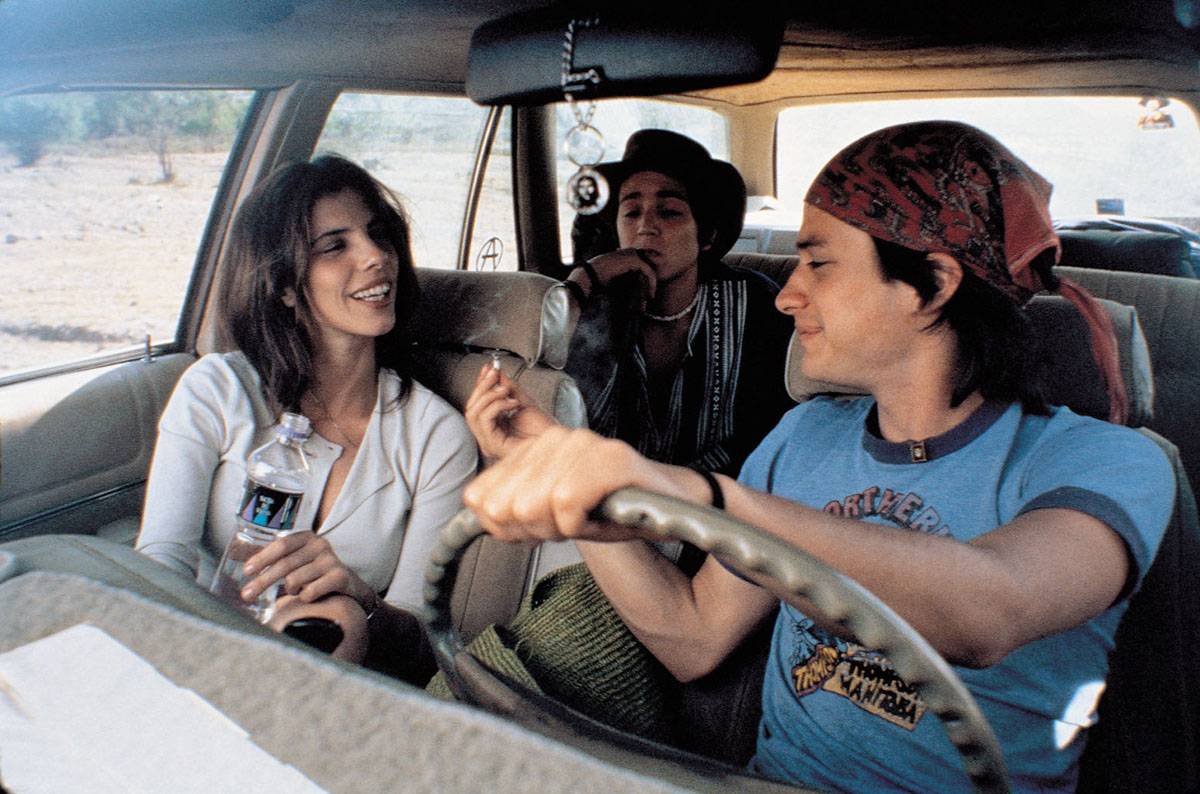

Y Tu Mama Tambien: Alfonso Cuarón’s feature debut remains his most satisfying film, hilarious and melancholy by turn, and sexy throughout. The central cast is wonderful, with a standout performance from a young Gael García Bernal, the pacing is ideal, and the undertones of political discontent and social concern add gravity to the proceedings. This is a film that combines coming-of-age tropes with social concern in wise ways and with an assured touch. It succeeds as a road movie too, but the film’s anxious heart is with its protagonists, uneasily growing up in changing times but entirely relatable.