Earlier entries in the Vegan Horror series have tended to focus on films with an animal rights subtext (even if their directors occasionally felt compelled to shout out, “It’s about meat”). The whole notion is founded on the idea of mining the signifiers to point out the underlying logic and related concerns.

vegan horror

Antonia Bird‘s film Ravenous is a number of things. It’s a horror, and a comedy, and an odd collision of vampire and cannibal tropes, and a frontier narrative. It’s also a vegan, feminist, and anti-colonial attack on mythologies of masculinist virility.

The zombie occupies a unique position in the cultural imagination. Neither living nor dead, neither human nor animal, it is a boundary-blurring figure.

It can be, and usually is, frightening in its monstrosity and lack of category cohesion, but it can be tragic, too: most zombie stories involve the shock and sadness of seeing loved ones become … not quite themselves.

When I began writing about horror cinema as a form of oblique artistic grappling with our real-life treatment of nonhuman animals, it was with enthusiasm and several convictions. First, that this approach would merge two of my primary interests, philosophical issues of animal rights and their aesthetic representation and also scary movies.

Eli Roth is a man out to generate strong emotions. Whether through his gleeful repurposing of ’70s cannibal exploitation schlock, or his recent, unfortunate foray into trolling what the internet has dubbed Social Justice Warriors (that is, generally speaking, people who care about things at all), Roth’s not the easiest guy to champion.

When I stopped by to chat with the good folks at We Love To Watch about the madness and overstuffed spectacle that is Predator 2, I briefly alluded to its animal rights themes, but assured the gracious hosts I wouldn’t burden them with that analysis on the show.

If we’re going to talk about vegan subtexts in horror cinema, we eventually are going to have to talk about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the macabre granddaddy of the trope.

Held up as “the ultimate pro-vegetarian film”, trumpeted by the perpetual attention-seekers and noted film critics at PeTA (in a list that also includes Lloyd Kaufman’s Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead, which is not quite as bad as ThanksKilling but still among the worst movies I’ve ever seen), and a mainstay of thinkpieces featuring “films with hidden activist agendas,” the subtext of Tobe Hooper’s horror classic is already well-established.

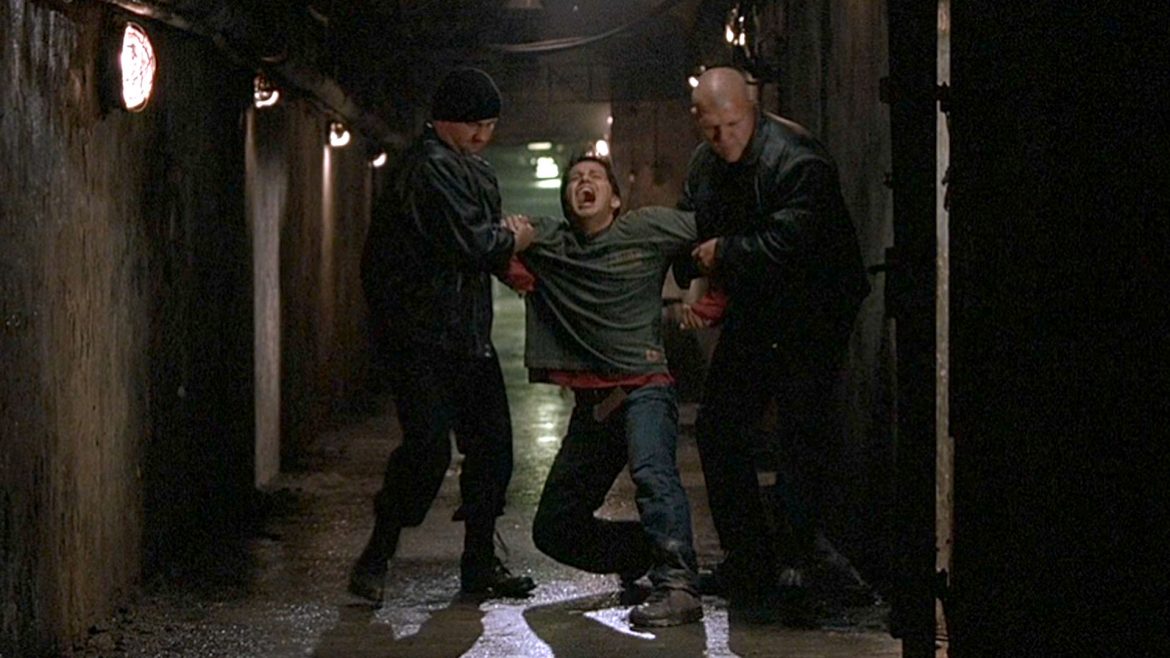

Many horror and sci-fi films play with themes drawn from our treatment of nonhuman animals and the natural world. From the Night of the Living Dead to the Texas Chainsaw Massacre movies, and on through pure exploitation and extreme cinema, the subtexts are often hard to miss — a focus on vulnerability, powerlessness, instrumental use.