The lovable rogue is a cultural fixture. In his more thieving modes (he’s canonically male, usually stealing hearts along the way), he steals and redistributes or returns the goods for safekeeping (Robin Hood, Indiana Jones); steals because he operates best on the margins and needs to outrun an already dodgy past (Han Solo, Mal Reynolds, Jack Colton); or simply steals because it’s fun, he’s good at it, and it beats working for a living, like Monsieur Leval or, well, Mr.

Steven Soderbergh

It’s an assumption, an article of faith, but it always bears repeating: every best-of list is a subjective snapshot, bound by what we could or would see, the genres to which we gravitate, the last-minute audibles called because we simply can’t bear to leave out a title.

Much has been made of the unconventional, even “game-changing” financing model that Steven Soderbergh employed to get his new Logan Lucky out to the world. And much more will be written about whether or not it “worked,” whether its success revolutionized the film industry — saving the mid-budget movie by wresting profits and control from the suits and placing them back in the hands of the creators — or if its failure spells doom for the model.

“In the event that find certain sequences or ideas disturbing, please bear in mind that this is your fault, not ours. You will need to see the picture again and again, until you understand everything.”

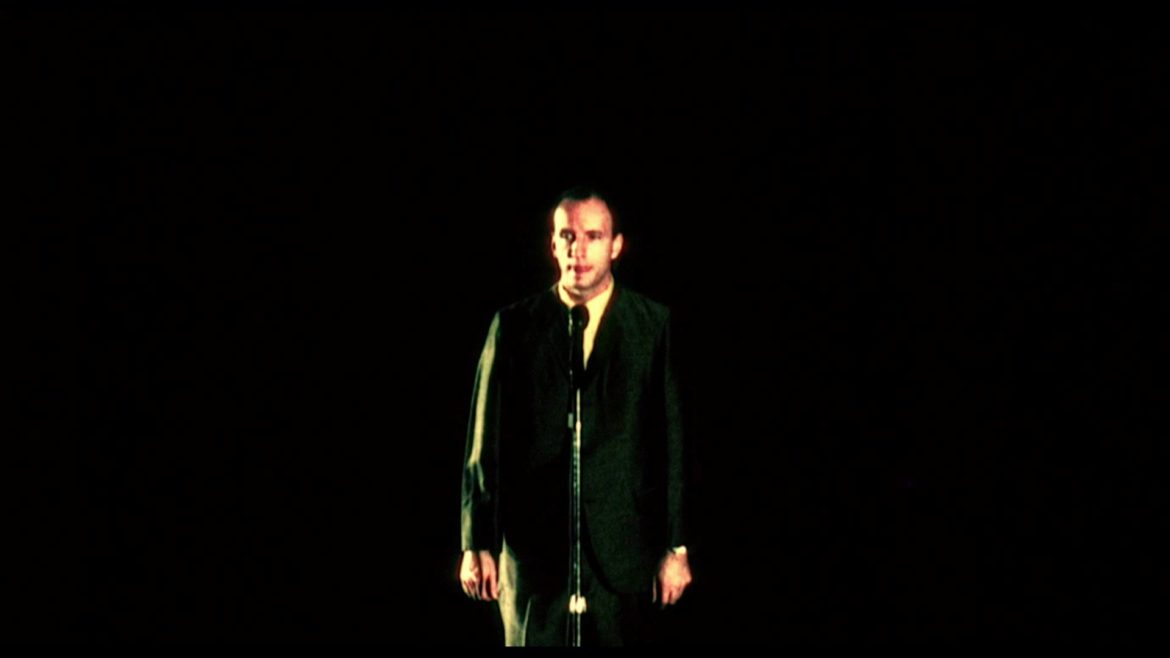

This delightfully caustic warning, uttered by director/star Steven Soderbergh in the first moments of the film, sets the tone for Schizopolis.