Dog Eat Dog has all the trademarks and tics you’d expect from Paul Schrader — twitchy griminess, awkward dialog, stray mentions of faith, ultra-violence, losers who just can’t win, cocaine, samurai references. But it’s overwhelming, mean-spirited mood connotes revenge more than anything else.

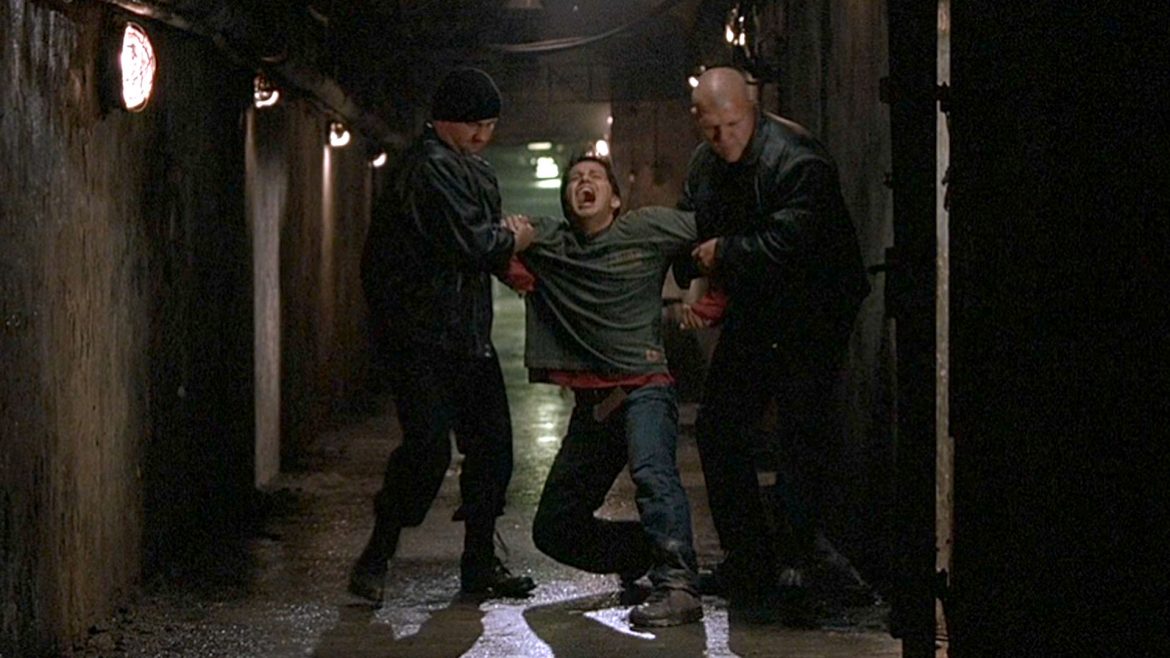

Hostel

When I began writing about horror cinema as a form of oblique artistic grappling with our real-life treatment of nonhuman animals, it was with enthusiasm and several convictions. First, that this approach would merge two of my primary interests, philosophical issues of animal rights and their aesthetic representation and also scary movies.

Eli Roth is a man out to generate strong emotions. Whether through his gleeful repurposing of ’70s cannibal exploitation schlock, or his recent, unfortunate foray into trolling what the internet has dubbed Social Justice Warriors (that is, generally speaking, people who care about things at all), Roth’s not the easiest guy to champion.

Many horror and sci-fi films play with themes drawn from our treatment of nonhuman animals and the natural world. From the Night of the Living Dead to the Texas Chainsaw Massacre movies, and on through pure exploitation and extreme cinema, the subtexts are often hard to miss — a focus on vulnerability, powerlessness, instrumental use.

When James Wan released Insidious in 2010 and the original The Conjuring three years later, it surprised a lot of horror audiences and critics. The director of Saw, and the producer of its string of increasingly grisly sequels, seemed to have taken a sharp right turn, abandoning what fans call “extreme cinema” and detractors dismiss as “torture porn” for haunted-house atmospherics and a more creeping variety of dread.