When I began writing about horror cinema as a form of oblique artistic grappling with our real-life treatment of nonhuman animals, it was with enthusiasm and several convictions. First, that this approach would merge two of my primary interests, philosophical issues of animal rights and their aesthetic representation and also scary movies.

Horror

Eli Roth is a man out to generate strong emotions. Whether through his gleeful repurposing of ’70s cannibal exploitation schlock, or his recent, unfortunate foray into trolling what the internet has dubbed Social Justice Warriors (that is, generally speaking, people who care about things at all), Roth’s not the easiest guy to champion.

If we’re going to talk about vegan subtexts in horror cinema, we eventually are going to have to talk about The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, the macabre granddaddy of the trope.

Held up as “the ultimate pro-vegetarian film”, trumpeted by the perpetual attention-seekers and noted film critics at PeTA (in a list that also includes Lloyd Kaufman’s Poultrygeist: Night of the Chicken Dead, which is not quite as bad as ThanksKilling but still among the worst movies I’ve ever seen), and a mainstay of thinkpieces featuring “films with hidden activist agendas,” the subtext of Tobe Hooper’s horror classic is already well-established.

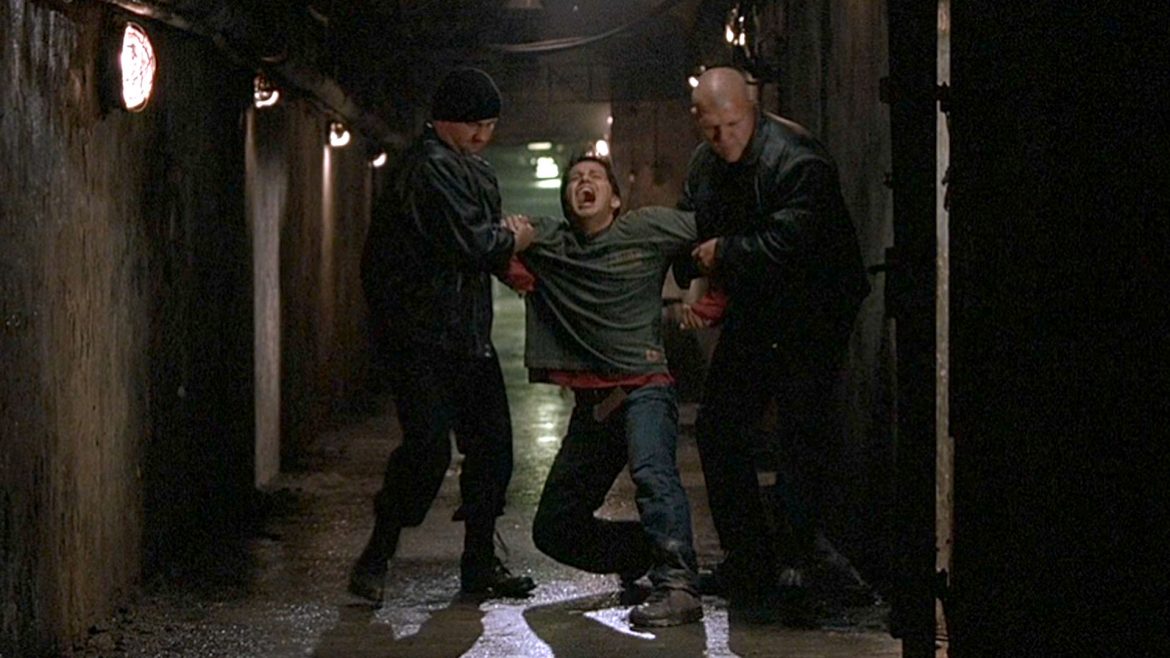

Many horror and sci-fi films play with themes drawn from our treatment of nonhuman animals and the natural world. From the Night of the Living Dead to the Texas Chainsaw Massacre movies, and on through pure exploitation and extreme cinema, the subtexts are often hard to miss — a focus on vulnerability, powerlessness, instrumental use.

A recent episode of the excellent We Love To Watch podcast focused on Motel Hell, a quite poor film with fascinating subtexts. It got me thinking about the prevalence of animal rights themes in film, and in horror specifically. Horror’s fixation on the notion of the human and the nonhuman provides a kind of secret key to understanding an unease at the root of modern existence.

It may seem peculiar to go back and talk about a film two years after its release, especially one as forgotten as 2014’s As Above, So Below – so let me explain why anyone should care about the film first.

It’s a general rule in clowning – and I know with that phrase I’m already in danger of losing some of you, but stick with me – that you have to do something really cool and skilled before you can fail amusingly.

Part of an ongoing effort to watch each of the films in Roger Ebert’s Great Movies series. The introduction and full list can be found here.

As our shared monsters and shadowy nightmare figures go, the vampire is particularly stubborn in its refusal to vanish from the scene.

Many horror movies are about external dangers coming to get you – monsters, demons, Dex Dogtective. But many are about the latent terror that was already there. Jennifer Kent’s brilliant, unsettling The Babadook is a recent example of the second sort.

Director Adam Wingard and writer Simon Barrett traffic in playful homage and neat subversion of other horror movies. Their 2011 low-budget collaboration You’re Next combined elements of home invasion and slasher flicks with an in-joke sensibility – a mumblecore Scream. With 2014’s The Guest, they went full-on John Carpenter, layering on the mounting dread and the insistent synth score, while drawing liberally (or borrowing wholesale) from the plot of The Stepfather and similar “who are you really?”

Katheryn Bigelow’s clever, mostly successful postmodern take on the vampire mythology opens with a nice bit of misdirection. Caleb, our pretty-boy protagonist, is goofing around with his crew of country fellas outside a Southern bar when they notice Mae, a lovely young lady awkwardly hanging out by herself.